Bruce Springsteen vs. Donald Trump: 10 keys to the critical patriotism of the last legend of American rock

The singer has turned his current tour into a warning about democratic decline in the United States. EL PAÍS reviews his career and political commitment

At 75, Bruce Springsteen is back in the spotlight. The American rock legend — who was born in New Jersey in 1949 — is currently on a European tour. A couple of weeks ago, he performed alongside Paul McCartney in Liverpool. And the Tracks II box set – featuring seven previously-unreleased albums that Springsteen recorded between 1983 and 2018 – was released on June 27.

On August 5, Peter Ames Carlin’s Tonight in Jungleland — a book about the recording of Springsteen’s legendary album, Born to Run (1975) – will be released. And, on October 24, the biopic Deliver Me From Nowhere — directed by Scott Cooper — will hit theaters. But these developments aren’t what put “the Boss” back in the headlines.

The singer — who campaigned for Kamala Harris — had initially remained silent following Donald Trump’s victory. However, he broke that silence this past May 14, in Manchester, U.K. What seemed like a mere continuation of his last concert tour transformed into an act of outright criticism of President Trump’s policies and a warning against the degradation of democracy that the United States is experiencing. The following day, Trump responded.

Springsteen has been building his identity as a committed artist over the past half-century. These are the 10 main milestones of his critical patriotism.

Head-on collision

“The United States is in the hands of a corrupt, incompetent and traitorous administration,” Springsteen declared. A traitor to the values he has reworked in his songbook for over 50 years.

The concerts on his current European tour have also become statements. He doesn’t waste a second. Before singing, he relentlessly attacks the Trump administration. He says that the country he loves — and about which he has spent his entire life writing songs — is going through a democratic emergency.

A few days after the first concert on his latest tour, the singer posted videos of his statements on social media. Donald Trump fired back, calling him an “overrated” and “obnoxious” guy who is “dumb as a rock” and a “dried out prune.”

Trump then posted an altered video, which shows him hitting a golf ball that knocks Springsteen off the stage. The singer responded by releasing an album titled Land of Hope & Dreams, which features some of his speeches, three songs filled with political criticism and hope, as well as Bob Dylan’s Chimes of Freedom (1964), which Springsteen has reissued 37 years after his 1988 version.

National crisis

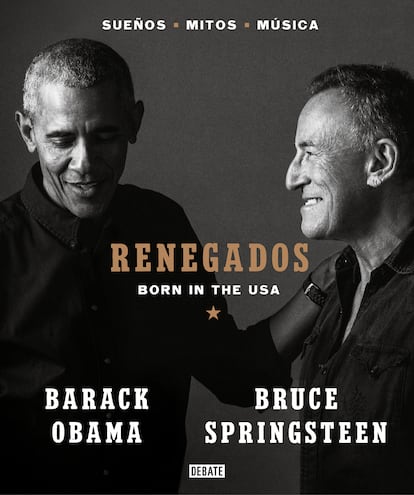

“Democracy isn’t automatic; it has to be nurtured, it has to be tended to. We have to work at it.” Barack Obama said this at the funeral of John Lewis, one of the heroes of the American Civil Rights Movement. It was near the end of August 2020, just weeks before the elections. A few days later, Obama traveled to Bruce Springsteen’s home to record a podcast with him. By then, the singer’s partisan commitment was already clear. The conversation between two friends blossomed into the book Renegades (2021), a dialogue about their musical tastes, their lives, their masculinity, but especially about the national crisis.

“If we don’t fix [economic inequalities], the country is going to fall apart,” Springsteen tells him at one point. “When folks lose that sense of place and status,” the former president notes, “when, suddenly, steady work alone isn’t enough to support your family or to be respected, and when you have chronic insecurity, there’s a bunch of policy stuff that has to be fixed.” The rapport between the two is clear.

Springsteen was also one of the latest guests on Michelle Obama’s podcast. He spoke about his experiences as a son, husband and father.

First round

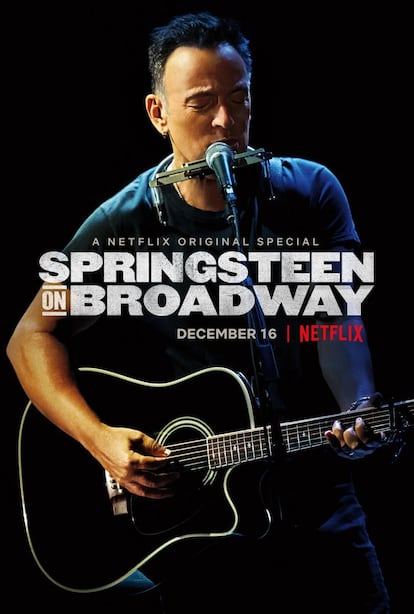

A week before leaving the White House, Obama treated his staff to an acoustic Bruce Springsteen concert. The performance — held on January 12, 2017 — included political commentary, which was interspersed between songs. It ended up being a rehearsal for the show Springsteen on Broadway. He gave 236 shows in a small Manhattan theater between October of 2017 and December of 2018. It was a journey through his own life that culminated in a patriotic statement. It was also his response to Donald Trump’s first presidency.

In 2016, Springsteen — after many years of psychoanalytic therapy — exposed his inner demons in his autobiography, Born to Run. The key was his complex relationship with his father… a psychiatric patient who could turn the house into a living hell. He remained a shadow that haunted him until he became a father.

On Broadway, he described his strict Catholic childhood and his youthful escape, but halfway through the show – before the performance of Born in the USA – he offered a political explanation for his work, connected to the first Trumpian moment of democratic decline. “These are times when we’ve also seen folks marching, and in the highest offices of our land, who want to speak to our darkest angels, who want to call up the ugliest and most divisive ghosts of America’s past. And they want to destroy the idea of an America for all. That’s their intention.”

Before the last song — like a preacher — he said goodbye to the audience with a rendition of the Lord’s Prayer.

Traditional songbook

At the end of August 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and killed more than 1,500 people across the state of Louisiana. A few months later, the city’s famous jazz festival was held.

On Sunday, April 30, 2006, Bruce Springsteen premiered his version of the gospel hymn Oh When The Saints Go Marching In and performed songs from a newly-released album, We Shall Overcome. The title track is a progressive anthem: it entered the songbook of the American Civil Rights Movement, popularized by — among others — Pete Seeger, who is depicted as a supporting character in the recent Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown (2024). Springsteen sang with folk patriarch Seeger at Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration. And solo, he sang at Joe Biden’s, in 2021.

An older Springsteen’s desire to connect his work and career to the history of the United States is very explicit in these sessions with Seeger. The rock figure embraced a tradition he hadn’t felt was his own, because it was the best way to reinvent himself as a political artist who is critical of his nation. Springsteen did this with folk music, along with country and soul.

Rising up after 9/11

The police fired 41 shots at the 23-year-old Guinean student Amadou Diallo. The officers were searching for a rapist and identified him as a possible suspect. When Diallo put his hand in his pocket to search for his ID, he was shot to death. For Springsteen, this was an example of blatant racism. And so, at the end of the E Street Band’s comeback tour in mid-2001, he sang a song denouncing it.

Police departments protested, calling for a boycott of the shows at Madison Square Garden. Even then-mayor Rudy Giuliani protested, asking him not to sing American Skin. He ignored them and was subjected to light boos. On that tour, he also premiered Land of Hope and Dreams, an elegy for the American soul, in which he works with the founding imagery of the nation.

A year later, after the 9/11 attacks, families of the victims played his songs at funerals to commemorate their deceased loved ones. In a fundraising television show, he performed My City of Ruins. It’s a prayer he’d previously composed: it describes a deserted, hopeless city. The doors of a church are open: he enters to pray and ask God that, together, they may rise again. This song is the centerpiece of his current tour and closed out The Rising, the album he released as a civic response to the crisis caused by the terrorist attack.

Protest song

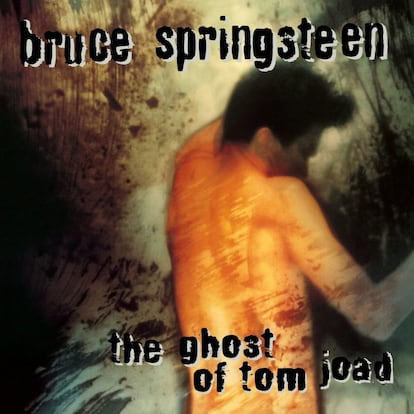

He hadn’t read The Grapes of Wrath (1939), but he had seen John Ford’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel. And he internalized a particular scene that lies at the heart of American progressive culture: the monologue that persecuted labor activist Tom Joad addresses to his mother. He won’t be with her, but she’ll be able to recognize him in the struggle for justice and the common good.

Springsteen embedded this monologue into the title track of a 1995 acoustic album. In his memoirs, he explains that it was then that he reconnected with one of the currents of folk protest music: the so-called “contemporary songs.”

For six months in California — where he was living with his wife, Patti Scialfa — he immersed himself in the human geography of the area, so that he could compose a new tableau of the disinherited of the Earth.

A Vietnam veteran reappears throughout his musical body of work. And, in the song Youngstone, the son of another veteran — this time from World War II — sees his world crumbling, because the steel mill that gave meaning to the town has closed: he’s a victim of globalization avant-la-lettre. But surely the key figure is the Latino who crosses the border in search of hope, whose life expectancy is dashed because his only chance of survival is to join the drug-trafficking networks.

The Cold War

The communist Free German Youth’s plan backfired. Protests against repression had erupted in the preceding months: the government of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was fed up with young people flocking to the wall to hear rock stars perform in West Berlin. Perhaps a Bruce Springsteen concert — part of his Tunnel of Love Express Tour — might calm things down. It was framed as an act of support for the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua (untrue) and the party’s old guard was presented with a narrative that the singer was a representative of the working class, who also spoke about the dark side of the American dream.

“I’m not here for any government. I’ve come to play rock’n’roll for you, in the hope that, one day, all the barriers will be torn down.” That phrase — sung between the chants of Born in the USA and Bob Dylan’s Chimes of Freedom — was heard not only by tens of thousands of excited young people, but also by the viewers watching the broadcast on television. The audience didn’t rush to tear down the wall — which fell a year later — but the spectacle transformed them, as Erik Kirschbaum documents in the book Rocking the Wall (2013). Two months after that concert, Springsteen joined the Human Rights Now! worldwide tour, on behalf of Amnesty International.

A cursed anthem

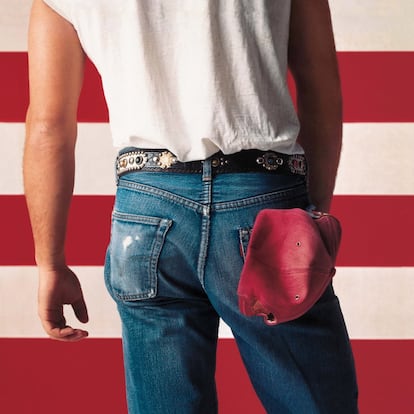

This Land is Your Land — the first version of which was composed by Woody Guthrie in 1940 — is considered to be the best song about the United States. “A promise of what our country should be,” in Springsteen’s words. It expresses a desire nurtured by the lessons learned during the Great Depression: the hope that, in the face of inequalities, the country — from east to west and from countryside to city — would be a land of opportunity for all. In the late-1980s, Springsteen began singing it in his concerts. He then began to shape Born in the USA (1984).

The hit song is a paradox of patriotism: while looking at the vast distance between defending power and defending the values of the flag, Guthrie’s values are adapted to a post-industrial society. The protagonist of his patriotic, cursed anthem is a bewildered war veteran. “I’m 10 years burning down the road / Nowhere to run ain’t got nowhere to go.”

It was the other side of Born to Run (1975). After youth, there’s the knowledge that comes from disappointment… both personal and collective. But the critical potential of Springsteen’s lyrics seemed to be undermined by Ronald Reagan’s self-serving interpretation of the song during the 1984 election campaign.

Dark side

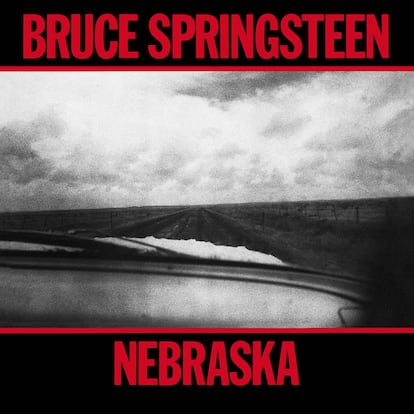

Two days after Reagan’s rally, Springsteen performed in Pittsburgh. And — before singing a song about an unemployed auto worker who becomes a murderer — he referenced the Republican: “The president was mentioning my name the other day. And I kinda got to wondering what his favorite album must have been. I don’t think it was the Nebraska album.”

That album — released in 1982 — is the darkest of his entire career and probably the one with the most legendary history. After the brutal success of The River Tour, he locked himself in his house in Colts Necks (a township in his home state of New Jersey) and recorded hours and hours of songs in his bedroom, alone with a guitar. These songs were supposed to be the basis for a new album with his band… but nothing compared to the purity of that raw sound.

“He sank into a loneliness more powerful than himself,” writes Warren Zanes in Deliver Me from Nowhere (2023). This excellent book forms the basis of the script for a Springsteen biopic starring Jeremy Allen White (the trailer looks promising). Nebraska is a dazzling exploration of the darker, wilder side of the prototypical white American man.

Dreams and reality

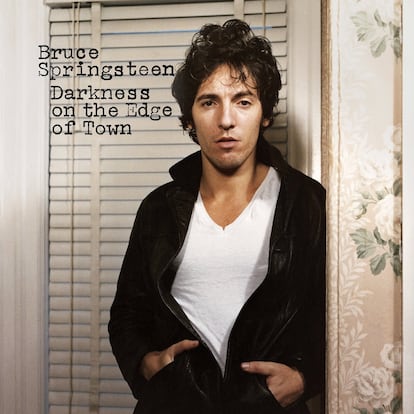

At 20, he played dumb to avoid serving in Vietnam. But digesting the trauma of that war — in which young musicians from his hometown died — was a trigger for his civic conscience. In 1978 — on one of his endless road trips across the United States, fleeing his ghosts — he bought a copy of Born on the Fourth of July (1976), by Ron Kovic. This autobiography by a Vietnam veteran inspired the film of the same name by Oliver Stone.

In a Los Angeles hotel, Springsteen met Kovic by chance, who took him to a residence for veterans. It was a transformative experience. A few days later, at a concert in San Francisco, he dedicated Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978) to Kovic.

The song exemplifies Springsteen’s great theme: the contrast between the American dream and reality. The voice — speaking in the first person — recalls his youthful past, which is contrasted with his present situation. He tells “Sonny” that he has settled on the dark margins of the city and society. “I lost my money and I lost my wife.”

Dissecting this vital sense of defeat — so as to gain self-awareness about his country — is the cornerstone of the political commitment of Springsteen’s songbook. It’s the same dynamic he would explore in The River (1980), which uses the war veteran, the unemployed person and the immigrant as its symbols.

Country, rockabilly, mariachi and more music from the frontier

The release of Tracks II won't change our assessment of Bruce Springsteen's career, but it does help us understand it more precisely. The box set includes seven albums with 83 previously-unreleased songs. They were recorded between 1983 and 2018, but this chronology could be misleading. The truly substantial part begins after the 1992 misfires that were Human Touch and Lucky Town.

We’re now hearing the songs that made up the artist’s search for alternative creative paths, as he attempted to revive his mature career. In his early-forties – after having already experienced his songwriting glory – Springsteen would explore other possibilities.

The cycle linked to Streets of Philadelphia (1993) – a song which occupies one of these recovered albums – led him back to composing works with contemporary themes, in a more pop-oriented vein. But we now know that he didn’t simply stick to one genre. While returning to acoustic and critical solitude in The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995), he ventured into country and rockabilly in Somewhere North of Nashville (2019). It's an example of his willingness to take risks, in order to become part of a North American musical tradition that he didn’t originally belong to. This created a new kind of genre altogether, which is even more evident in Springsteen’s following album, Inyo (2025). It's an album from the border, touching on Mexico, California and Texas. Mariachi bands can be heard, while the song titles are steeped in Chicano imagery.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition