Why Woody Guthrie’s guitar was a killer of fascists

Music, like culture, has the power to defeat right-wing extremists and their antidemocratic ideas rooted in xenophobia, racism, homophobia and sexism

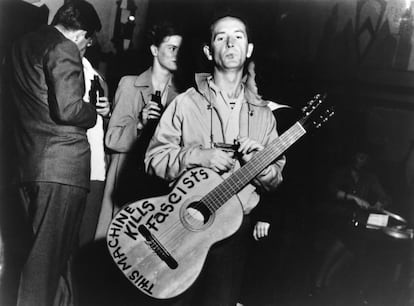

There was a time, not so long ago, when we believed fascism had met its eternal demise. In the 1960s, Donovan, hailed as “the British Bob Dylan,” strummed a guitar with a bold message on it, a tribute to his hero Woody Guthrie. The words read: “This machine kills.” Donovan deliberately chose to omit a single word — “fascists.” Years later, when an interviewer asked why he had altered Guthrie’s iconic message, Donovan replied, “I reckoned fascism had breathed its last.” How wrong he was. How wrong we all were.

Fascism never completely dies because some people never lose the desire to engage in what dictionaries define as “authoritarian and antidemocratic behavior.” There’s a 21st-century mindset linked to fascism, the far-right, authoritarian, ultranationalist political ideology and movement that emerged in the early 20th century. In a democratic society, it is crucial to recognize that those who think differently are not automatically fascists. Merely having diverse viewpoints should not warrant the casual usage of this term. It is important to reserve the “fascist” label for ideas and attitudes that actively promote authoritarianism, antidemocratic activity, and even nationalism or corporatism, often at the expense of equality, tolerance and justice.

The major concern now is that fascists have managed to infiltrate democratic societies and influence others who may not consider themselves extremists. These individuals may not hold extreme views but have aligned themselves with what are now called “alternative right-wingers.” These leaders openly embrace fascist or right-wing extremist ideologies. They have ignited a political revolution by capitalizing on discontent, provoking and mobilizing dissatisfied citizens. This phenomenon is happening in a Western world where turbocharged capitalism often prevails.

Argentine journalist and author Pablo Stefanoni published a book a few years ago about how today’s rebels are mostly right-wingers. He wrote that the rise of anti-progressivism is defined by its deliberate political incorrectness, and the right has co-opted righteous indignation from the left. The pressing issue is the institutional infiltration of right-wing movements, as seen today in Spain, which will hold crucial elections on July 23. This electoral cycle revealed how these movements are actively shaping the narrative of conservative and traditional right-wing parties, their influence growing with each passing day.

In the 1930s, as Woody Guthrie traveled from coast to coast across the United States, he witnessed the struggles of marginalized and disaffected people firsthand. Through his songs, Guthrie not only exposed their reality but also proposed ways to bring about change. With a sense of urgency that seems distant today amidst all the slick commercial and promotional strategies, Guthrie’s music spoke to the present while envisioning a near future. After all, tomorrow cannot afford to wait when faced with the relentless surge of fascist ideas. That’s why Guthrie pleaded, “Good people, what are we waiting on?” in his song, Tear the Fascists Down.

Woody Guthrie’s guitar didn’t kill fascists because it fired bullets. It killed by neutralizing the fascists. Music, like culture, has the power to defeat right-wing extremists and their antidemocratic ideas rooted in xenophobia, racism, homophobia and sexism. Guthrie fought using ideas, language, music and the shared desire to build a better future together.

They say he borrowed “This machine kills fascists” from workers in an American factory supplying the Allied war effort during World War II. They wrote it on their lathes. Regardless, the message forever became linked to his guitar and served its purpose. Woody Guthrie paved the way for many artists and generations, with Bob Dylan being the most recent and most captivating follower.

If Guthrie’s guitar was able to kill fascists, it was simply because it was heard. As Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck once wrote, “There is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of a people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.” Guthrie’s music and presence should endure. To sing or stand up against fascists and the current wave of right-wing extremists, one must embrace the ideology — at the very least, the spirit — of a democrat. It’s the ideology of refusing to remain indifferent when the ghosts of the past reappear, the very ones that Donovan thought were long gone.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.