Despite the scorn, Jane Austen is still alive 250 years later

Once dismissed as corny, the British novelist is more fashionable than ever thanks to her rediscovery by new generations

By now, in 2025, it’s hard not to have noticed that we’re in the year that marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. For months, new editions of her novels have been gleaming in shop windows, some published in commemorative boxes, such as those released in Spanish by Planeta, Penguin Random House, Alianza, Nórdica, and Alba, a publishing house that has always considered Austen one of its flagships.

Tributes are taking place all over the world, especially in the United Kingdom, where the author is so highly regarded that she is often compared to Shakespeare, as Harold Bloom did in his famous Western canon. The scope of the celebrations is evident in London bookstores. The new releases table at Hatchards, the London bookshop that made Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway dream, is full of carefully curated and colorful editions of all her works, but also of suggestive new titles, such as Jane Austen and George Eliot: The Lady and the Radical (Biteback Publishing, 2025) by Edward Whitley, or Living with Jane Austen (Cambridge University Press, 2025), a moving book by Janet Todd, who has devoted much of her life to studying her works. Faced with such a beautiful treasure, any “Janeite” (the name by which Austen fans around the world are recognized) would have felt in paradise.

In addition to the reissues, the Jane Austen centenary in Spain leaves other valuable contributions, such as the publication of the essays Two Afternoons with Jane Austen (Alianza, 2025) and In the Footsteps of Jane Austen (Ariel, 2025), both by María Laura Espido Freire, an English philologist and the writer who has contributed most to disseminating her work in Spain. New surprises are planned for autumn, such as The Novel Life of Jane Austen (Impedimenta, 2025), a graphic novel by Janine Barchas and Isabel Greenberg, and My Aunt Jane (Anaya, 2025), an exquisite biography aimed at young people, also written by Freire. And it is possible that as December 16 approaches, the day Jane Austen would have turned 250 (she lived from 1775 to 1817), other literary and audiovisual proposals will appear (such as the Miss Austen television miniseries released earlier in the year).

“It’s obvious that Austen is being read a lot in Spain,” says Martín Schifino, editor at Penguin Random House. “There are constantly editions appearing for all audiences, both young adult and adult, romantic in style, but also for university students, in paperback, with inflected edges, illustrated…” Centenary releases help a lot, he adds, although he believes that film adaptations in recent decades have also boosted sales.

Misogyny and ignorance

However, if we look back, it’s also clear that Jane Austen hasn’t always enjoyed such a healthy publishing presence in Spanish. “She’s an immense author,” says José C. Vales, one of her main translators, “full of wonderful details and jokes that haven’t always been understood.” The first work translated into Spanish was Persuasion, in 1919, a century after her death. And, until not so long ago, mentioning her name in intellectual or university circles was tantamount to being labeled a sentimental or saccharine reader. Misogyny? Probably. Ignorance? Definitely.

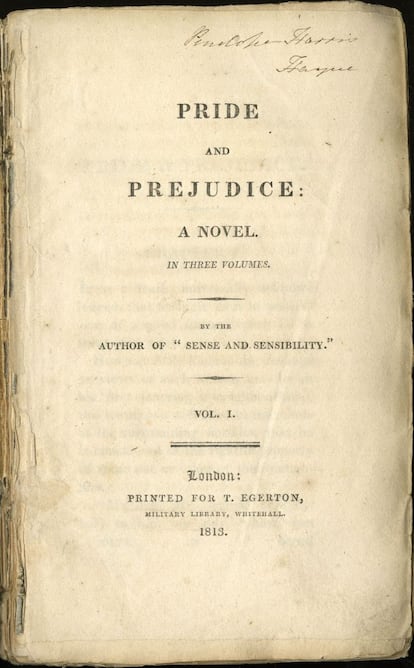

Postwar translations also helped to pigeonhole Austen as a minor author, a “romance novelist,” a derogatory label if ever there was one. Proof of this is the curious edition of Sense and Sensibility published in 1958 in the Spanish Revista Literaria Novelas y Cuentos under the most eloquent title: Toward Happiness by Way of Love. Or the no less curious version of Pride and Prejudice published in the Violeta Collection by the Molino publishing house, with a cover illustration by Joan Pau Bocquet Bertrán, who also drew entertaining comics. But among all these relics, the most notable is Mansfield Park, published by Tartessos in 1943. In addition to its amusing title — a copy of another French translation — this version of Mansfield Park hides an anecdote that would have made Austen herself laugh. Guillermo Villalonga, its translator, decided to take the liberty of omitting the 10 chapters in which the characters rehearse a play, precisely the same ones that literary critics, with Nabokov at the head, consider not only the most accomplished but also one of the great summits of the 19th-century European novel.

Although Sergio Pitol and José María Valverde had already produced important translations of Emma in the 1970s, it was not until the 1990s that Luis Magrinyà — responsible for numerous classic editions at the publishing house Alba and himself the translator of Sense and Sensibility — published Austen with the care and seriousness that a classic author such as her deserved. Among other things, it was Magrinyà who commissioned Francisco Torres Oliver, National Prize winner and pioneer of Gothic literature in Spain, to produce the dazzling translation of Mansfield Park for Alba, which, needless to say, includes every chapter. “I’ve been rereading Mansfield Park and refreshing what Nabokov explains about the work,” Torres Oliver comments in a generous email exchange. “It’s an analysis that makes you love literature. I’ve also seen that Martín de Riquer compares it to a string quartet; I think that, musically, it would be better to compare it to a Baroque concerto, if only because of its three-movement structure. But we all know that its essence is theatrical: it’s a drama, or a comedy of intrigue, as Nabokov wants it, whose pieces she works with millimetric precision.”

Returning to centenaries, they not only constitute an exceptional opportunity to revise translations and reissue works, but also, as Magrinyà points out, for new generations to offer different interpretations of established authors. Or, as A. S. Byatt would say, they serve to judge the extent to which the presence of a writer like Jane Austen lives on among us. In the case of Spain, it is true that Austen has required two centuries for her figure to become better known. It has also taken two centuries for her to find her true place in bookstore windows and on library shelves. But, despite the obstacles and numerous disdainful remarks, she has finally managed to enchant and possess Spanish-speaking readers. And if she has succeeded, it is because her ghost lives on.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.