Queen Charlotte wasn’t Black and George III wasn’t mad: The half-truths of the hit series ‘Bridgerton’

This week marks 204 years since the death of the British monarch, who suffered from porphyria, a disease unknown to medicine at the time. The prequel to ‘Bridgerton,’ far from an accurate portrayal of history, nevertheless faithfully narrates the illness of the king popularly known as ‘Farmer George’

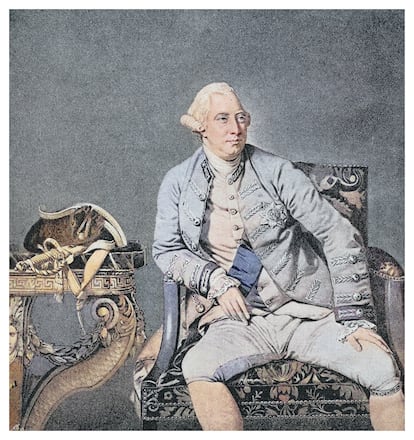

On the cold morning of January 29, 1820, King George III, monarch of the United Kingdom, took his last breath at the age of 81 at Windsor Castle. The day marked the end of one of the longest reigns in the history of the British monarchy, with the blessings of his descendants: Queen Victoria (1819-1901) and the recently deceased Elizabeth II (1926-2022).

George was the son of Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, and his wife, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. He hailed from the House of Hanover, the German dynasty that reigned in Great Britain (later, in 1801, the United Kingdom) beginning in 1714, after Queen Anne I died without descendants, leaving the thrown to Queen Victoria of Hanover and her cousin, Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. In the midst of World War I, and as a result of growing anti-German sentiment in the United Kingdom, the Hanovers decided to adopt the Windsor surname. Curiously, George III was the first of this dynasty to be born in British territory, and the first whose mother tongue was not German, but English.

The life of George III is fascinating from the point of view of history, and especially from the perspective of the history of medicine, as the king is believed to have suffered from porphyria, a hemophilia that he inherited and that was passed down his bloodline, ultimately affecting even the Spanish Royal Family: several of the children of King Alfonso XIII and Queen Victoria Eugenia, popularly known as Ena, were afflicted with the disease. Ena was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England, known as the “grandmother of Europe” because she had so many descendants that today it is rare to find a member of a European dynasty who is not related to her.

Almost nothing in George III’s life happened as it seemed it would. He was born premature, and was baptized immediately after birth under the assumption that he would die within hours. He was the second son, but the first male and thus the future heir after his father, Frederick Louis, ascended the throne. But due to a bad relationship between the reigning monarch — George III’s grandfather — and George II, the future king’s father was banished in 1737. The bad relationship most likely stemmed from the fact that the father and son had been separated when the little boy was just seven years old, leaving Frederick Louis in the care of the court in Germany. His parents went to live in England when they became heirs to the throne on the occasion of the accession of George I. Frederick did not see his parents again until he was an adult, finally arriving to England, but as a complete stranger to his own family.

Despite his reputation as a womanizer and a spendthrift, he finally found stability after marrying Augusta of Saxony, with whom he would father nine children, George III being the second born, but the first male, and thus heir to the throne. At the age of 44 he died before his own father, so he never wore the crown himself, and passed the title of Prince of Wales to his son, the future George III, who became king the day his grandfather, George II, died, on October 25, 1760.

A newly crowned king with no descendants — not the most comfortable position to occupy in a reigning royal house, but one that would resolve a year later following an exhaustive search for eligible European princesses. The chosen future queen was Charlotte, protagonist of Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, the prequel to the hit Netflix show Bridgerton, in which the monarch is portrayed as a Black woman — the first in a series of creative licenses that, while permitted by fiction, do not, of course, accurately reflect the real historical figure herself. In portraits and descriptions from the time, Queen Charlotte is consistently represented as white. The historian John Watikings described the queen as “rather small, but her shape fine, and carriage graceful; her hands and neck extremely well turned; her hair auburn; her face round and fair; the eyes of light blue face round and white, her eyes light blue...” Although at the time, marriages were arranged, it was customary to send portraits of prospective wives so that the groom could get a sense of the possible candidates and make his choice. George received two portraits of Charlotte that are preserved in the Royal Collection of the British Crown, in which she is depicted as having pale skin and blue eyes. There is no historically valid reason that she might be portrayed as Black. The only fact that might explain certain features is that the queen’s ancestors, specifically María Afonso, born five centuries before her, may have been Moors rather than Jews — something that in any case lacks a basis in history, given that, in the Middle Ages, the category of “Moor” referred to a religion and not an ethnic group, whose members could be from anywhere, including, of course, Europe.

No one can say for certain whether the couple was happy in their marriage; what we do know is that they had 15 children, of whom two died (a low number considering the high infant mortality of the time). The Netflix series focuses exclusively on the couple’s marital relationship and the king’s illness, which is, indeed, historically accurate — but George III was much more than his ailment. Such a long reign necessarily brings many events to a country. And so it was. “The reign of George III of Great Britain marked the arrival of a certain stability for the Crown,” explains Rocío García-Bourrellier, Professor of Modern History at the University of Navarra. “His predecessors, prince-electors of Hanover, had prioritized the direction of the Germanic territory over their obligations as British monarchs, which caused disaffection among the people and part of the nobility. George III was the first Hanoverian born and raised in the United Kingdom, his mother tongue was English, and he managed to charm the population with his pleasant folksiness, earning him the nickname Farmer George. In the realm of politics, however, he is considered a king with absolutist tendencies, who minimized the power of Parliament in making strategic decisions for the state, such as the signing of the Treaty of Paris [which ended the Seven Years’ War],” she says, adding another point: “He’s also blamed for the loss of the 13 American colonies. Later, he had the foresight to call on William Pitt the Younger as a trusted minister despite their personal differences, which led to better economic results for the country. Suffering from porphyria, his last years were spent between medical treatments and periods of lucidity. Because of his illness, a major debate arose as to who should hold power in the event of royal incapacity: Parliament, the Prince of Wales or the Prime Minister.”

In fact, the three points outlined by Garcia-Bourrellier were fundamental to George III’s reign, yet none of them are even mentioned in the Netflix series. The loss of the 13 colonies marked a major change in British foreign policy and, of course, a radical shift in relations between the two countries. George III’s reign began in 1760, when the territories had already begun to organize for revolution, ultimately declaring independence on July 4, 1776, with the colonies forever separating from Britain and forming the United States following the military victory of American troops at the Battle of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. On September 3, 1783 an armistice was reached with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which put an end to the War of Independence.

The king’s illness is accurately narrated in the series and is, indeed, something that really happened. At the time, however, medical professionals treated the symptoms as signs of insanity, providing the monarch with treatments as unpleasant as they were ineffective. Porphyria is a defect in the metabolism of red blood cell molecules, responsible for transporting oxygen. One of its symptoms is suffering from hallucinations and mental confusion, among many other ailments, hence the belief, at the time, that the king was mad. Today it is a disease that can be managed with medication.

Another historical reality that the series fails to even mention is the king’s absolutist exercise of power during his reign — an unusual approach for a monarchy such as the British, which in almost every instance has operated under strong parliamentary control. As the British philosopher and MP Edmund Burke warned, England was in danger of a revival of monarchical absolutism, with an unstable government, because George III insisted on unconstitutionally interfering in politics by using his friends and a “secret cabinet” to influence Parliament.

But the Netflix series is a product designed to entertain, not to convey the true history, so viewer can relax and enjoy their popcorn, knowing that much of what appears on screen never really happened — starting with the fact that Queen Charlotte was not Black.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.