Andy Warhol and Brazilian Pop Art converse in São Paulo

Two exhibitions allow viewers to appreciate the similarities and differences between the work of the American icon and the tropical version

Pop art enthusiasts can take advantage of the opportunity to visit São Paulo, where, seemingly by chance, two major complementary exhibitions are being held at the same time for several weeks.

One is dedicated to Andy Warhol (1928-1987), a global star and one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, thanks to a body of work that seems tailor-made for these times of Instagram and fleeting fame. Visitors can reconnect in person with the originals of works central to the popular imagination, such as Marilyn Monroe, Mao, and Pelé, The King of Soccer.

The other exhibition is an immersion in what Brazilian Pop Art was like in the 1960s and 1970s, at the height of the dictatorship, through the work created by around 100 artists. Here, political criticism is an essential ingredient, along with icons such as Che Guevara, Roberto Carlos, and yes, also Pelé.

The organizers attribute the coincidence of both exhibitions in the great Brazilian metropolis to mere chance. Pop Brasil: Vanguarda e nova figuração, 1960-70 is the title of the season’s major exhibition at the Pinacoteca, a public museum. The exhibition, which has just opened, brings together 250 pieces by around 100 artists, including a significant number of female artists whom the curators have selected to place front and center alongside their male contemporaries. The exhibition will be open until October and will then travel to the Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires (MALBA) in Argentina.

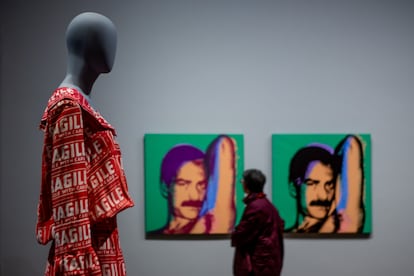

Andy Warhol: Pop Art!, which closes at the end of the month at the private Brazilian Art Museum FAAP, is billed as the largest exhibition outside the United States dedicated to the unique artist, unbeatable self-promoter, and founder of The Factory in New York. It brings together 600 original works from the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the epicenter of the steel industry and Andrew Warhola’s hometown.

Pop art took its first steps in the United Kingdom, but reached its peak in the United States. Although Brazil tropicalized pop art with it intense colors, humor, irony, images from television and advertising, and industrial reproduction techniques such as silkscreen printing, it has distinct hallmarks that distinguish it from the American style, explains Pollyana Quintella, one of the curators.

“While the United States is undergoing a process of full-blown industrialization and creating a consumer society with mass-produced quality products, in Brazil, industrialization is more contradictory and delayed, fraught with conflict,” he says in an interview at the Pinacoteca. “Here, the workmanship of the works is more precarious.”

In the United States, playfulness prevails, while social criticism is more cynical, says the specialist. During that time, Brazil suffered the years of military rule, which shut down Congress and intensified censorship. This repressive and somber atmosphere was challenged by creators. “Brazilian artists understand art as an instrument of social transformation and embrace its political role, intervening in public debate,” Quintella emphasizes.

Some of the works refer to resistance against censorship or the criminalization of poverty. It was in this context that one of the iconic works of this period in Brazil was born: the 1968 print by Hélio Oiticica with the motto Seja marginal, seja herói (Be marginal, be a hero). It shows a man lying dead on the ground, his arms crossed, after shooting himself while cornered by the police.

This was one of the silkscreened banners that starred in the so-called Happening of the Flags, in a square next to Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, promoted by a group of artists eager to turn their backs on museums, occupy the streets, and democratize art. It’s ironic that, almost six decades later, these pieces, located one by one with enormous effort, solemnly welcome us into an art gallery.

The Warhol exhibition was packed with visitors on a recent Sunday. Few passed up the opportunity to take a selfie or pose next to the portraits of Elvis, Liza Minnelli, Blondie, or the unique reinterpretation of the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. Warhol, with an eye for business and another for questioning the limits of art, persuaded wealthy and powerful people in the U.S. to buy a painting of Comrade Mao for their living rooms in 1973, a year after President Nixon’s historic visit to Beijing and in the midst of the Cold War.

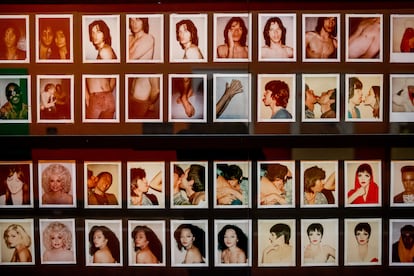

The Campbell’s cans, which launched him to stardom, reign in one of the FAAP museum’s galleries, which display other everyday objects that Warhol reinterpreted long before the verb entered the vocabulary. Also on display are pieces from his early days as a cartoonist for luxury brands, experimental films, and several series of his famous Polaroids, the hallmark of that New York art factory where legendary parties mingled with established figures from the world of art, rock, and fashion. These somewhat yellowed portraits showcase a who’s who of the moment: Muhammad Ali, Bianca Jagger, Truman Capote, Sonia Rykel...

Two metro stops away, back at the Pinacoteca, the 1966 work Adoração by Nelson Leirner plays with ambiguity, with a neon silhouette of Roberto Carlos surrounded by Catholic saints, who is both praise and criticism. The real Roberto Carlos got involved and attended the opening. In the same room, astronauts watch, from a painting on the opposite wall, other Brazilian stars such as Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Chico Buarque, and Elis Regina, who made their debut on popular television competitions.

Brazilian Pop Art also explored female desire and inequality, the great scourge that has plagued the country for centuries. Here, as a reminder, are Rubens Gerchman’s Elevator Social and Elevator Service (1966), exhibited together for the first time. Far from being a relic, classist elevators that distinguish between tenants and staff are common in upper-middle-class towers.

These two pop art exhibitions are connected by Pelé, a tribute to his role as the most universal Brazilian of all time. A global icon, thanks to the fact that his artistry with a soccer ball coincided with the arrival of television in millions of homes around the world. Alongside him, other paintings celebrate the national team that lifted Brazil to the heavens by winning five World Cups. “We’ve made a small selection,” says the curator, “because it would take a whole exhibition of pop art and football alone.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.