The spectacular life of Mikhail Baryshnikov: Fleeing the USSR, Hollywood romances, and that role in ‘Sex and the City’

The renowned Latvian dancer remains deeply engaged in his work at the helm of the artistic center that bears his name, and recently joined Pedro Almodóvar for one of the filmmaker’s major nights in the United States

When the third season of And Just Like That premieres later this month, we’ll find out whether Carrie Bradshaw continues her relationship with Aidan — the boyfriend who rivaled the eternal Mr. Big for her heart. Aidan was one of the main draws of the most recent episodes in the Sex and the City sequel, but Carrie’s romantic history includes many names, most of them fleeting.

One however has left lasting imprint: Aleksandr Petrovsky, also known as “The Russian,” who persuaded her to move to Paris. He was played by Mikhail Baryshnikov, now 77 — one of the greatest dancers in history and a leading figure of the prestigious Kirov Ballet. To Clive Barnes, the former dance critic for The New York Times, he was “the perfect dancer.”

The Latvian-born dancer is amused that people who’ve never seen him perform recognize him. “At least they remember something, though they actually don’t remember my real name. They say, ‘oh it’s Alexander Petrovsky,’” he told The Telegraph.

Baryshnikov says that Sex and the City fans approach him more often than fans of anything else he’s done. “The irony of me working in theatre for 40, 50 years and they remember you for that TV show. But that’s fine, I understand why… That’s America!” he told The i Paper.

But he’s grateful for the boost in popularity. “I thought that I would have a couple of months and do a couple of episodes but then they asked me stay for the whole last year. It was a lot of fun.”

It wasn’t his first venture into the world of film and television. In addition to his acclaimed ballet specials — which earned him two Emmy Awards — he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for The Turning Point.

Baryshnikov also knew what it meant to be hounded by the media. In the 1970s, he became a household name in the United States after his high-profile defection from the Soviet Union — though he dislikes that term.

“My first English phrase was, ‘I’m not a defector, I’m a selector,’” he said in an interveiw. “I chose another country. I was just a regular person who wanted to change his circumstances. For me, it was as natural as moving from Riga to St. Petersburg.”

The U.S. welcomed his talent with open arms. He became a fixture of New York’s nightlife scene, and his romance with actress Jessica Lange made him a favorite of the tabloids.

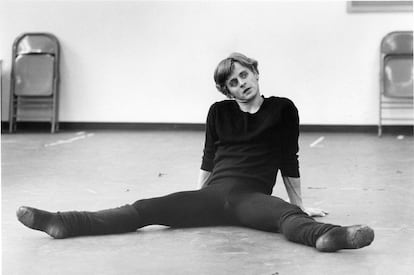

A life in dance

Baryshnikov was born in Riga, Latvia. His father was a strict military man to whom he didn’t feel particularly close, and his mother was a dressmaker who killed herself when he was 12. She loved art and instilled in him a passion for ballet. He began dancing at the age of seven, and by 16, he was studying under Alexander Pushkin, one of the greatest ballet masters of the Soviet Union. At 19, he joined the Kirov Ballet of the Mariinsky Theater, the most prestigious company alongside the legendary Bolshoi Ballet.

Standing at just 1.65 meters (5′5″), shorter than a ballerina en pointe, he seemed destined for secondary roles — at least within the rigid Soviet system. But his international tours made him begin to question whether he was in the right place to fully develop his art. He felt he didn’t fit within the strict order and conventionality of the Soviet ballet school, and he began to wonder if he truly belonged there. It wasn’t a political issue — it was an artistic one.

He wouldn’t be the first to leave his country: in the 1960s, Rudolf Nureyev had sought asylum in Paris, and a decade later, Natalia Makarova never returned to the Soviet Union after a performance in London. Nor would he be the last: Alexander Godunov, the Bolshoi’s principal dancer, would later make headlines with his high-profile defection to the United States.

He has always maintained that it wasn’t a planned escape, but rather an impulsive decision.

“In Russia I was never a [...] political dissident,” he told People magazine years later. I was a civil servant. The Kirov was sponsored by the government. I had all the privileges and material things I wanted. Enough money, a car, beautiful apartment. I was right there next to sons of ministers in the elite. But I couldn’t travel abroad when I wanted, I couldn’t work with people I wanted."

Over time, however, he has become politically outspoken, especially following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “Ukraine is our friend. I danced Ukrainian dances, listened to Ukrainian music and singers,” he said in an interview with The New York Times. “I am a pacifist and an antifascist, that is for sure.”

His defection, or “selection,” wasn’t easy. The previous defections of other dancers had alerted the KGB, and surveillance was tight. During a joint tour of Canada by stars from both the Bolshoi and Kirov, a group of Canadian friends offered their help. On June 29, 1974, at 6:30 p.m., just before the final performance, Baryshnikov met with a lawyer in Toronto and signed the necessary paperwork. The lawyer advised him not to return to the theater, but Baryshnikov didn’t want to harm the company and decided to give his last performance. Those who witnessed it said his hands were shaking as he held his partner.

The plan was simple, but any small mistake could ruin it. When the curtain fell at 10:30 p.m., two friends would be waiting to take him to a safe house. From there, they would change cars and drive to another house in a rural area. However, a delay with the curtain caused the show to start 15 minutes late, and the audience’s enthusiasm led to an unusually long round of applause.

To make matters worse, they begged him to attend a reception immediately afterward. Baryshnikov was sure the delay would foil the plan, but as he left the auditorium, while one friend eluded the KGB agents guarding him and another avoided autograph seekers, he ran to the waiting car and escaped.

“The defection was like a thriller — with a comic twist," he told People. “It was arranged secretly through friends. I was running, the getaway car was waiting a few blocks away as we were boarding on the group’s bus. KGB was watching us. It was actually funny. Fans are waiting for me outside the stage door, and I walk out and I start to run, and they start to run after me for autograph. They were laughing, I was running for my life. It was very emotional moment.”

“Soviet Dancer in Canada Defects on Bolshoi Tour,” read the headline on the front page of The New York Times. The news was a major blow to the Soviet Union; all of Baryshnikov’s friends were interrogated and forced to write letters urging him to return. This included his father, who at the time was teaching military topography at the Air Force Academy.

“I knew the K.G.B. services would be interviewing him and asking him if he was involved, and if he would write me a letter or something. He did nothing. I must say, ‘Thank you, Papa. Thank you for not bending over.’”

The dancer wrote to thank him, but his father never responded. He died in 1980.

Hello, America

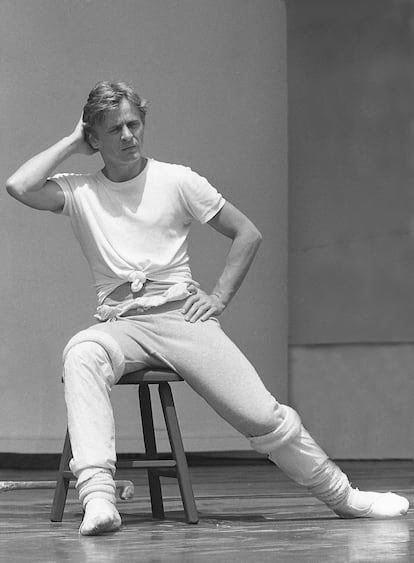

Baryshnikov joined the National Ballet of Canada but soon made his way to the United States. For four years, he was a principal dancer with the American Ballet Theater, and in 1978, he joined the New York City Ballet. He became something of an obsession for a country still deep in the throes of the Cold War, paraded around like a prized trophy.

The press adored him, and the world of cinema soon began to take notice. He was popular not only for his dancing but also for his looks, his apparent fragility, his melancholic air, and his blue eyes. Despite this, he loathes being labeled a sex symbol. “People who know me, it has nothing to do with reality,” he told Haaretz. “I am not a skirt chaser, you know, I am not a sex maniac. I am not nice-looking, I am not tall, I am not a hero by any means. And I am not a macho kind of a guy, so what’s this sex all about?”

His first film was The Turning Point (1977), a drama set in the world of ballet, in which he starred alongside Shirley MacLaine and Anne Bancroft. He received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor, one of 11 nominations for Herbert Ross’s film, though he didn’t win. Despite the Oscar nod, it took him another eight years to return to Hollywood. White Nights (1985), alongside Helen Mirren, Isabella Rossellini, and Gregory Hines, told a story of dancers and defections similar to his own. Though it didn’t win over critics, it was well received by audiences.

Baryshnikov’s popularity continued to rise. He launched a perfume and a clothing collection and frequented Studio 54, mingling with the likes of Martha Graham, Andy Warhol, Liza Minnelli, and Mick Jagger. However, he insists he wasn’t a regular. “How could I be there until 6 a.m. when I had to be at 10 a.m. at dance class. I was there maybe three times altogether.”

He was nearly out of the spotlight when the producers of Sex and the City reached out to him. His friends advised against participating, but he saw an episode of the show and liked it.

“It was a very curious challenge,” he says. “On television you have to work very fast; they’re changing texts at the last second, you have to improvise in front of the camera. It’s a great school of professionalism. And when all these actors live together for six years and do series and series, just like that, for them it’s like they arrive, it’s in character. For me it was harder, but I’m glad I did it.”

He was no stranger to the limelight. By the late 1970s, his romance with actress Jessica Lange had placed him on every tabloid cover. They were young, good-looking, and famous. In the early 1990s, Lange told Vanity Fair that they met thanks to Milos Forman at a 1976 party hosted by screenwriter Buck Henry in Hollywood. “I remember seeing him standing at the pool. I had never seen anybody so white. It was like he was transparent.”

Lange admitted she didn’t initially know who he was. “In fact, I confused him with Nureyev. I didn’t know anything about the ballet world; I’d been totally unaware of his incredible defection. I had no idea the scope of his fame.”

Their connection was immediate, and their relationship lasted seven years, but they never lived together or shared a daily life. “We couldn’t have really lived together— we had these knock-down-drag-out fights," saidn Lange.

Their relationship wasn’t monogamous, and Lange was aware of his reputation as a womanizer. The dancer had been romantically linked to several famous women, including Ursula Andress, Liza Minnelli, Isabella Rossellini, and Janine Turner, star of Northern Exposure. But she didn’t mind the rumors.

Everything changed when Lange became pregnant with their daughter, Shura, and moved into Baryshnikov’s home. They hoped the arrival of their daughter would bring them closer, but it ended up driving them apart. Lange fell in love with playwright Sam Shepard, her great love, while Baryshnikov moved on with dancer Lisa Rinehart. They had already been in a relationship, and today, they are married with three children.

After triumphing on stages around the world, his career as a dancer is now a distant memory, largely due to injuries. “I abused my body,” he admits. “I went to certain extremes. I had 12 operations, just pushing it, being stupid a little bit, but it was interesting.”

Today, his main pursuits are theater, photography, and Baryshnikov Arts, the artistic center that bears his name — a name that continues to symbolize the entire world of dance. Last week, he was alongside Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar at a tribute held in his honor at Lincoln Center in New York, and just last Tuesday, he delivered the message for International Dance Day 2025.

“It’s often said that dance can express the unspeakable. Joy, grief, and despair become visible; embodied expressions of our shared fragility,” said Baryshnikov. His fragility — and his strength — have reached millions of people.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.