The Chicano mural that overcame censorship to shine in the heart of Los Angeles

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County is bringing back Barbara Carrasco’s ‘L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective,’ a 1981 masterpiece that spent decades in storage

In the lower corner of Barbara Carrasco’s monumental 1981 mural, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective, there is an assembly of characters. Among them are Chicana activists like Anna Nieto Gomez, sports icons like Fernando Valenzuela, Mayor Tom Bradley, and celebrities including Jane Fonda, musician Rick James, and actor Martin Sheen, who is of Spanish-Irish descent. Sheen, the star of Apocalypse Now specifically requested to be included in the painting to transcend time, according to Carrasco. The mural also features young artists who helped create the work, and tucked among them is a smiling woman with glasses — the painter’s own mother.

“She said to me, ‘Why is everyone there except me? … So I included her,’” Carrasco recalls, standing in front of her mural, which, after decades of censorship, can finally be appreciated once again.

Since mid-November, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective has been on display in the new wing of the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History County (NHM), one of the city’s most celebrated cultural landmarks. It has been renovated and expanded for the upcoming 2026 World Cup and the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. In this luminous space, sunlight streams through large windows, illuminating the fossilized remains of Gnatalie, a 22-meter-long sauropod with greenish-hued bones. The remains share the space with Carrasco’s mural, which like the dinosaur, has emerged from obscurity to share its story with the world.

“I definitely think I was a victim of censorship, but I always felt a responsibility to fight against it. Not just to accept it, but to fight it,” reflects Carrasco, now 70. In 1981, at just 26 years old, she was already carving out her path as an artist. Having studied art for two years at the University of California, she was working at the time creating topographic maps for the Los Angeles Community Development Agency. When an architect approached her about designing a mural for McDonald’s corporate headquarters across the street, she jumped at the opportunity. Yet weeks later, her design would run into several obstacles.

“One day I arrived at City Hall with [labor leader] Dolores Huerta. I wanted her to see part of the mural, and I noticed that some panels were missing. So I went to the loading dock in the basement and saw workers loading the mural into a large truck. They had orders to take it to a warehouse in Boyle Heights,” the artist recalls. After making several urgent calls, Carrasco managed to halt the relocation. However, Huerta made it very clear to her what the politicians saw as the destination for her work. “You have to get this mural out of here,” she told Carrasco.

Thus began the decades-long odyssey of L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective. For several years, the mural became like a kind of art meteor, appearing fleetingly for brief exhibitions in museums and galleries across the United States. Wherever it was displayed, its reputation preceded it: it had been censored for what it revealed.

One of the warehouses that housed the mural for months was the headquarters of the United Farm Workers (UFW), the influential agricultural union led by Huerta and Cesar Chavez, located at the foot of the Tehachapi Mountains northeast of Los Angeles. “I worked with them for many years making banners for conventions and events, so they let me store it there for free,” Carrasco recalls. The UFW headquarters had been a hospital for tuberculosis patients. The mural was kept in the building’s basement, a dark and damp space. “The colors stayed super vibrant,” she adds.

In 2012, then-president Barack Obama designated the UFW headquarters as a national landmark, which required Carrasco to remove the mural and move it to a warehouse in Pasadena. It has only left the building on rare occasions to be exhibited at the MIT in Boston and the Autry Museum of the American West in Griffith Park.

The mural, towering nearly five meters high and stretching 24 meters in length, offers a Mexican perspective on the history of Los Angeles — a city founded by migrants from the Mexican state of Sonora. Carrasco’s design is rooted in the city’s original name: El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río de Porciúncula (The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of the Porciúncula River). Carrasco chose this imaginary monarch as the focal point to narrate the events that have shaped the city over the centuries. The queen is actually based on one of Carrasco’s sisters. In her hair, different vignettes illustrates pivotal moments from the city’s history, beginning in prehistory.

The mural features scenes such as the construction of the Spanish missions in the late 18th century, built through the labor of Native Indians. It highlights the lives of the Gabrieleños and Tongva peoples, the war for Mexican independence from Spain, and early milestones like the city’s first automobile, the construction of City Hall, and the central train station built by 3,000 Chinese laborers — a community that profoundly shaped the identity of Los Angeles.

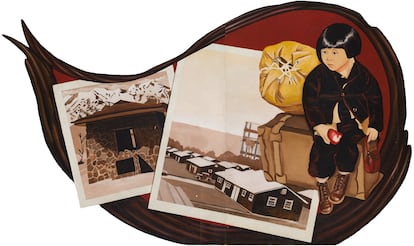

Carrasco identifies the scene she believes led to the mural’s censorship. It depicts a Japanese girl sitting on a trunk of family belongings, symbolizing the 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly exiled or interned in concentration camps during World War II. “I was asked to remove that image even though I have beautiful letters from the Japanese community saying that the episode must be included so that history does not repeat itself,” she says, gesturing to the image in question.

A few meters away, there are other controversial scenes. A red vignette shows a float symbolizing the 1871 massacre of 22 Chinese people, a racially motivated atrocity that took place where Union Station now stands. Carrasco initially included a noose to represent how the victims were massacred, but McDonald’s executives asked for it to be removed. It was the only change the fast-food company insisted on.

The mural bears visible traces of its history with censorship. In the version on display, some panels remain colorless or roughly sketched. This was because Carrasco and the artists who helped her stopped working on it as soon as they learned of the piece’s fate. “I think these unfinished parts are part of history, which is why they didn’t want me to touch or retouch it, even now,” explains Carrasco.

Some contemporary accounts suggest that the mural was not officially censored, but rather sidelined due to a personal clash between Carrasco and Gary Williamson, the architect overseeing the project. The artist acknowledges that a major point of contention was the rights to the mural. The agency overseeing the mural sought to retain control, but Carrasco took preemptive action by placing a trademark logo on the initial sketch and registering it at the Library of Congress in Washington. This move enraged her superiors.

Four decades later, the residents of Los Angeles can finally see the mural about the city’s history. After years of obscurity, the mural’s display at the NHM stands as a testament to Carrasco’s vision and her determination to tell the city’s story from a fresh — and controversial — perspective. “I am Mexican, and even though I am a poor Mexican, I tried to tell the story in a more inclusive way than it was told back then. Many people left us out, as if we didn’t exist. That happened in more inclusive museums too, but it doesn’t happen like it used to,” says Carrasco.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.