Gang of Four, the last dance against nostalgia from the band that redefined post-punk

Kurt Cobain imitated them, R.E.M. supported them, the Red Hot Chili Peppers would never have existed without them. The most indefinable group of the English scene of the 1970s says goodbye: ‘We were never commercial. We never participated in that big spectacle’

Jon King lands in New York in 1976 and at the airport someone hands him a piece of paper with a skull on it and a warning: do not enter Manhattan. A student of fine arts at the University of Leeds, King is in the city because he has won a scholarship to write his final dissertation: an in-depth article on the great American artist Jasper Johns. His friend Andy Gill, from a different course year, decides to join him on the trip. There they meet Mary Harron, who will be their local guide. Over the years, Harron will direct cult films such as American Psycho or I Shot Andy Warhol, but in the late 1970s she is still a young journalist writing for the newly born Punk Magazine, which covers the avant-garde sounds coming out of the Lower East Side before anyone else. She has time to show them these New York streets with a bad reputation because she has just broken up with her ex, the drummer of a curious band, a mix of rock and poetry, led by a certain Patti Smith.

“She had a flat in possibly the hippest street in the entire world ever, Saint Marks Place,” King recalls. The singer who embodies the idea of cool, Blondie’s Debbie Harry, lives two blocks away. Beat writer William S. Burroughs, accused of killing his second wife but a revered counterculture figure, lives down the street. Joey Ramone, rock’s most famous mop-haired, leather-jacketed man, lives opposite. King, Gill and Harron spend their mornings scouring art galleries for their article and their nights at the first Talking Heads, Dead Boys, or Richard Hell gigs at CBGB. Everyone they meet plays in a band and assume they do too. They let them assume. “More or less everyone in the room became famous.” When they return to England, King, Gill and their friend Hugo Burnham, also an art student, decide to call the bluff. Leeds is not New York, but a young music scene is emerging around their university. This is how Gang of Four was born.

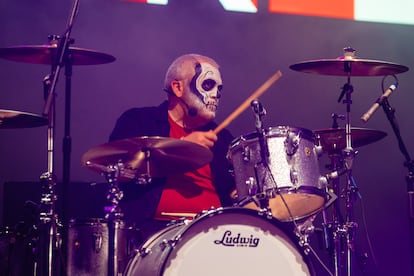

Half a century later, after breakups and reconciliations, Gang of Four is preparing to say goodbye, having become a cult group. Kurt Cobain once said that Nirvana started out as a copy of them — although it is true that he said the same about the Pixies and Scratch Acid; without them the Red Hot Chili Peppers would never have existed — “we were playing a big concert in Pasadena in 1981 and a naked guy jumped out of the crowd and grabbed me and held on, it was really funny. That was Flea jumping on stage naked” — and R.E.M., who started out supporting them, cite them as one of their greatest influences. Their legacy is immeasurable despite the fact that they never enjoyed commercial success. The big farewell will include 28 concerts in the United States and a handful more spread around the rest of the world. For now, they have already passed through Mexico City for the first and last time to scratch the itch of playing in the former D.F., at the Hipnosis festival.

Why the goodbye now? “I just like the idea of pulling down the shutters and saying: ‘That’s it. I think it’s just time to call it quits,’” says King, the band’s lead vocalist, prosaically. It’s not because they feel old, even though they are already pushing 70. “All musicians are in charge of playing their own material for as long as they like. The blues music that Hugo and I and Andy and Dave revered, the Chicago blues from the 1950s, those guys are playing to the age of 90 if they wanted to.” Rather, it’s because it’s time to stop. That saying about burning out rather than fading away, written by Jeff Blackburn, popularized by Neil Young, and martyred by Cobain when he included it in his suicide note.

It’s also a kind of declaration of principles: a war against the nostalgia consuming the modern music industry, against the tours by bands that return after years apart to play their old hits in search of one last taste of relevance. “We’re not a nostalgia band because we’re kind of an outsider band. We’re not part of the mainstream, and we were never commercial. We never participated in that big spectacle,” says King. “There are these very specific nostalgia tours that go around the U.S. every year that feature just 70s or 80s acts, all of whom have at least one hit, so they do three or four songs, and it’s fun, but we would never be asked to be part of that because we never had a hit,” agrees Burnham, the band’s drummer.

Unsuccessful and unclassifiable

Perhaps their lack of success is due to their style: hard-hitting rhythms, heavily influenced by reggae and funk, but with the power and dirtiness of the punk that dominated the alternative scene of the 1970s in England. Guitars like rusty saws and energetic voices, slow-digesting anti-formula pop songs. Not even the lyrics fit in with the rest of the groups of the time and their chewed-up social slogans. They maintained radicalism and political criticism, but from the more subtle approach of a group of art students, also influenced by that original trip to New York: Television, the Velvet Underground, David Bowie... To classify the unclassifiable, critics placed them under the umbrella of post-punk.

King pontificates: “Post-punk is a sort of an invented category. Our music only sounds like itself and so you can hear our influence in all sorts of musicians, and of course we were influenced ourselves by other artists. I think the reason that Entertainment! [the band’s first and most-acclaimed album] is still playing now and people still reference it is because it doesn’t sound like anything else. [There were] so many people of your age at the gig and the music meant something to them. Because our music is not empty, it’s great fun, it’s really loud, it’s really aggressive and it’s really danceable, but it is about stuff that I think everybody sort of thinks about.”

He launches into a diatribe against traditional punk: “You listen to a Sex Pistols record and actually it’s not very interesting. The lyrics are pretty good, but the music is a bit like Black Sabbath, they sound like a pub band. It doesn’t push any musical boundaries. It’s not like listening to Miles Davis or Jimi Hendrix.”

— And Gang of Four is?

— Exactly.

Burnham takes over: “At the time, it was outrageously exciting, compelling, it was part of the Zeitgeist of living at their time, the politics that we’re going on, the shift musically. But listening to it now it’s nostalgia. It’s fun, but it doesn’t have the same thing that it had, whereas Gang of Four wasn’t of a specific time; it’s not a matter of nostalgia for a certain period in time.”

Times have changed, life remains the same

An example of that timelessness they so defend? This interview was conducted by video call on November 5. King and Burnham were in the United States and the world did not yet know that Donald Trump would soon have access to the nuclear button again. “Here Hugo and I are in the United States with this election with the great anxiety that a fascist might win. I mean, the things that we sang about are relevant now: militarism, oppression, attacks on women’s rights.”

While Gang of Four was taking its first steps, Margaret Thatcher came to power in the UK and swept everything away. “Britain was a disaster,” King says. These were years of social and racial tension, economic hardship, miners’ strikes crushed by repression, mass unemployment, battles with the police in the streets, and the rise of the far right. “There was a very real threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, there were proxy wars in Africa and in the Middle East. Every household in Britain was sent a pamphlet about how to survive the inevitable nuclear war,” King recalls. Much like now. “That’s what really inspired me and Hugo and Andy and Dave to get together to do something that was radical. Obviously we failed miserably, but we wanted to change the world for the better.”

King still lives in England, has other projects, and is writing his memoirs, which focus mostly on the band’s early years. Burnham moved to the United States in 1988 and, after Los Angeles and New York, now lives in Boston and works in a university performing arts department. Gill, the guitarist, died in 2020. He was replaced by David Pajo. The bassist position has changed the most over the years.

Times have changed, life goes on as usual. Guitars are no longer popular. Bands don’t sing about politics. The music industry is conservative and most of the last remaining dinosaurs on stage are boring. “Rock music has declined in importance because there are far fewer acts talking about reality and people crave that; they want something that means something,” says King. “We thought we were living through the end of days, so you want to write songs about the end of days while you’re still alive. Now it’s got an end of days flavor about it. Maybe that’s always the case. I can’t think of many songs right now that have got the quality of the end of times about them.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.