The old story of defeated empires: ‘The Inca rulers spoiled their children, while the Aztecs were told they were going to die in battle’

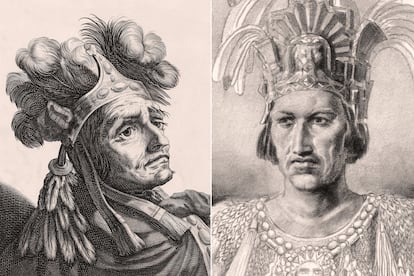

Peruvian anthropologist Luis Millones and Mexican archeologist Eduardo Matos speak with EL PAÍS and reflect on their new book, which deals with the figures of Moctezuma and Atahualpa, the last great pre-Columbian rulers

Two very wise gentlemen sat at a table to reflect, with a century-and-a-half of experience between them. They have at their disposal enormous amounts of knowledge, data, arguments and nuances regarding major issues of continental history and the life of the ancients: as in, those who lived in what is now called the Americas, before the arrival of the Spanish.

On one side is the Peruvian Luis Millones, one of the most renowned anthropologists of the Southern Cone. Millones has analyzed the life of the Inca people with devotion and ease. On the other side is the Mexican Eduardo Matos, an eminence of Mesoamerican archaeology. He’s responsible for the rescue of the remains of the old Aztec capital, from the depths of modern Mexico City.

Millones and Matos recently met up in Guadalajara, as part of the International Book Fair, to present their latest work together. Available only in Spanish and translated as Moctezuma and Atahualpa: Life, Passion and the Death of Two Rulers, it’s a comparative study of the life of the last great pre-Columbian leaders. “We had already written a previous book: Mexicas and Incas,” Matos notes, “motivated by that interest in knowing, in comparing the two great civilizations that emerged in [Latin America].”

“[Regarding] this book in particular… we went to a luncheon with a Peruvian researcher who lives in Mexico. And I said to Lucho (Luis), ‘Hey, do you see us writing about Moctezuma and Atahualpa?’ That was three or four years ago. And, well, we did it!”

They ended up writing a text that was rigorous, lucid and reader-friendly all at once, far from the stylistic flourishes of the academy, which tends to be a hiding place for great ideas that are waiting to germinate. Now, there’s no surprising news about the characters: much of what’s read in the book about Atahualpa and Moctezuma is already known to those who are familiar with Latin American history. But what’s important is the authors’ effort to contrast the two figures and to impose one on the other — the Inca on the Aztec and vice-versa — to understand who they truly were, how they came to lead their empires and how they acted in situations that only the two of them had to face. In their hands, they had their own worlds: the Inca Empire (Tahuantinsuyu) and Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire. The two rulers created a unique, unrepeatable experience, which is recorded in the book’s 200 pages.

Atahualpa and Moctezuma led starkly different lives. The former faced the Spanish conquest almost without realizing it, while he was still washing his hands of blood from the war of succession he had waged against his brother, Huascar. He had barely been able to enjoy his victory over the vast lands of the old Andean empire when the Europeans arrived. On the other hand, Moctezuma had reigned in Tenochtitlan for more than 15 years, a time of splendor in the Aztec empire, which spread its power from Lake Texcoco to the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. This is the principal and most obvious difference between the two rulers.

“The problem [for the Inca ruler] was the excessive extension of Tahuantinsuyu,” Millones explains. It was a territory that included what’s now Ecuador and Peru, as well as parts of modern-day Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. “A formula had to be found to govern that [vast territory], because, of course, there were rebellions everywhere,” he adds. “The Incas managed to establish a certain imperial order, a language. And Huayna Capac (the father of Huascar and Atahualpa) then proposed dividing the empire, on the border of what would be Peru and Ecuador today. One son would govern one, while the other would keep [the other half]. But then, before he died, Huayna Capac, who was ill, was asked several times about the line of succession. He would say one name, then another. It didn’t solve anything,” Millones sighs.

Then, war broke out. “The establishment of a formula that would allow the two ambitious brothers to coexist didn’t work,” the Peruvian anthropologist continues. “And the nobility that accompanied each son had its own interests… at its core, the growth of the empire was due to personal interests,” he reflects. “There was no philosophy of war or death behind it. On the other hand, in Tenochtitlan, [the Franciscan friar Bernardino de] Sahagún wrote that, when young Aztecs were born, it was said, ‘you were born here, but you will die on the battlefield, where you should. Either killing your enemies, or being sacrificed to the gods.’ In the Inca Empire, they spoiled their children,” Millones chuckles.

Matos, however, is a bit more cautious. “Well, in both societies, the warrior aspect is very important. From the moment the Aztec [subject] was born, if the child was a boy, the midwife performed a whole ritual, took the umbilical cord, made a little bundle and gave it to a warrior in the family and buried it on the battlefield, like a kind of magic league. If it was a girl, no, [the cord] was buried next to the hearth… as I’ve said in some conferences, there was no women’s liberation [in that society],” the archeologist jokes. “The differences between one [brother] and the other may have been numerous, but there was also a series of very important parallels between the two characters. Within the family scuffles, the appointment of the tlatoani (the sovereign) involved discussions about who was going to be chosen. In general, they looked for someone who was deeply religious — for ideological control — and a good soldier. That’s how they chose Moctezuma.”

The Sun — the cult of the star — also links both empires. Millones writes that “in the Aztec world, [the Sun] was born to change a world that was shrouded in darkness.” Then, he contrasts: “The Incas considered themselves to be children of the Sun.” Matos reflects: “The Sun has always been fundamental in agricultural societies. Both [the Aztecs and the Incas] were agricultural, as well as military. The main Aztec deity, Huitzilopochtli, led the Aztec forces… but he was a solar god who was born to combat darkness, the Moon and the shadows. In a certain way, when the tlatoani died, it was thought that the Sun had died. And another had to be found.”

The discussion about the last pre-Columbian rulers calls for an analysis of their persecutors: Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. “There’s a brutal difference. Cortés — despite all the trials that were brought against him — [managed to] maintain a legal relationship with Spain,” Millones explains. “The general deal with the Crown allowed the transition from conquest to viceroyalty to be possible, without major wars. In the Peruvian case, Pizarro was killed a few days after having conquered [the territory]. Pizarro’s plans didn’t exist; he quickly disappeared from the scene, while Cortés remained there for years. In Peru, it took until the fifth viceroy, due to the clashes between the conquerors and the Crown. So much so that Pizarro’s brother was crowned king of Peru for four years, breaking all relations with Spain.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.