Elizabeth Taylor was fed up with her own beauty

The documentary ‘The Lost Tapes’ contains the confessions of the actress at the moment of her greatest global fame. She said she was frustrated by the constraints of Hollywood stardom and eager to be recognized for her talent

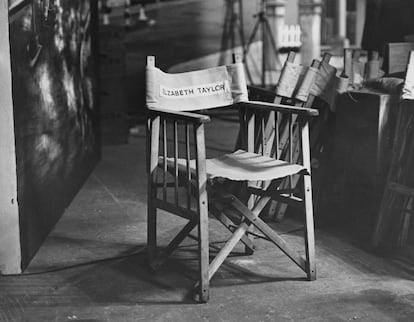

She was one of the most beautiful living beings ever to appear on the big screen, but she spoke of it as if it were a curse. Elizabeth Taylor could not imagine herself not being famous, because she had been a celebrity since the age of 10. She was the first star to suffer from the paparazzi phenomenon: journalists would try to sneak into her house by any means, even posing as plumbers. And her stormy private life — she was married eight times to seven men — made her fodder for the tabloid press. What she really wanted was to be recognized for her talent as an actress, which is not the same as being a movie star, and she regretted that she only achieved this on rare occasions.

The confessions of the diva par excellence can be heard in her own voice in Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes, available on Max. In 1964, when she was 32, Taylor had a series of recorded conversations, totaling around 40 hours, with Richard Meryman, a journalist for Life magazine and author of biographies of Hollywood figures (some of which were presented as autobiographies). The conversation gave rise to the book Elizabeth Taylor: An Informal Memoir, which did not show the journalist’s signature. It was not until after the writer’s death, in 2015, that these tapes were discovered, in which the actress expressed herself with enormous frankness, trusting that they would never be reproduced. Film director Nanette Burstein has given shape to this HBO documentary, produced by J. J. Abrams, which revolves around Taylor talking about herself, accompanied by archival footage and interviews with some of her Hollywood colleagues.

At one point, Taylor gets desperate with Maryman, who insists on asking her about her beauty. The journalists asks her if she realizes that she is a sex symbol, a sexual goddess. “You’ve asked me that 19 times!” the actress protests. And she answers: “I’m a girl, I’m a woman. I don’t feel special.” She also mentions some of the times she felt discriminated against, harassed or threatened, precisely because she was attractive. The most disturbing: one of her husbands, the sinister Eddie Fisher, pointed his gun at her head and said: “Don’t worry, I won’t kill you because you’re too pretty.” She goes so far as to confess to the interviewer: “I’m looking forward to getting fat, obese, flabby.”

Taylor suffered from what her public image had become. “I think I have the image of a superficial person,” she says. “I suggest something illicit because of my personal life. But I am not illicit or immoral.” Her own father called her a whore for her relationship history when she left Fisher. And she was especially hurt when the Vatican newspaper wrote that she deserved to lose custody of her children. Her successive marriages were frowned upon in her time, although with today’s eyes they portray a free woman who sought stability but knew how to break off a toxic relationship (and hers were so more than once).

She had not studied acting, having spent part of her childhood in the studios (starting with There’s One Born Every Minute in 1942). But she boasted of her instinct, of her ability to truly believe in each character. She admitted her frustration with the roles that were available to her: “I am not happy with what I am or what I have done,” she said. “I am a movie star who has been able to act a couple of times.”

Two of her shoots are described in detail, those in which she shared the screen with Richard Burton (and, it is said, the sexual tension between them went beyond the screen). One is the super-production Cleopatra, the first time that an actress was paid a million dollars. The job took much longer than expected because, halfway through the shoot, Taylor came down with a serious case of pneumonia and was unable to return to the set until two years later. When she did, for the scene of Cleopatra’s triumphal parade before the masses in Rome, the extras really cheered her.

And the other is Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a complex drama in which she finally achieved her goal of looking ugly (well not exactly, but she was made up to look older and heavier), which earned her a second Oscar and was a great source of pride for her. Hidden behind Martha, she explained, she felt free and could be rude. However, she had very bad memories (“embarrassing,” “horrible”) of BUtterfield 8, the film with which she had won her first Oscar after three nominations without a prize. She believes that they gave it to her out of pity for her health problems: “It was because of the tracheotomy.”

At the end of the documentary, there is a hurried account of what happened to Taylor after the 1960s, before dying in 2011 at the age of 79. It briefly touches on her lowest moments, her addictions to alcohol and other drugs, her inevitable physical decline, her time in a rehabilitation clinic (where she met her last husband, Larry Fortensky). Her involvement in the cause of AIDS gets more coverage, starting with the death of her friend Rock Hudson in 1985, which was praiseworthy at a time when the disease carried a terrible stigma. She says that many of her friends belonged to the LGBTQ+ community, at a time when it was not possible to come out of the closet. There would be no Hollywood, she says in the tapes, without the homosexual community.

The Lost Tapes does not offer any deep revelations about the actress’ career, but she seduces us with her voice and her melancholy. The original material determines everything. The film is guilty of the same bias that infuriated Taylor, the same bias exhibited by Meryman and, therefore, also apparent in this article: the focus on her beauty and her marriages instead of her career. Her appearance was so dazzling that few people saw the artist who was there.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.