This is how a 150-ton stone was moved thousands of years ago to complete the Dolmen of Menga

A study reveals the advanced mathematical, astronomical and geological knowledge that was used to build one of humanity’s first stone buildings, located in southern Spain

The Dolmen of Menga in Antequera, in the southern Spanish province of Málaga, is the oldest and largest of those located on the Iberian Peninsula. It was built between 3,800 and 3,600 BC and is crowned by five large slabs. Until now, experts wondered how it was possible that in the middle of the Neolithic period, more than a thousand years before the first pyramids of Egypt were built, these enormous stones could be moved and placed with millimetric precision, orienting them towards the sunrise for astronomical purposes.

Ten years of research reflected in a study published in the open-access scientific journal Science Advances offer a surprising answer: they were dragged from a quarry located about 2,800 feet away. This was done by preparing a track with leveled sleepers mounted on a system of sleds that allowed them to be steered in any direction. For the Spanish researchers who wrote the scientific article, “the extraordinary dimensions of some of the structural pieces of the dolmen required sophisticated design and planning, a large mobilization of manpower, as well as perfectly-executed logistics.”

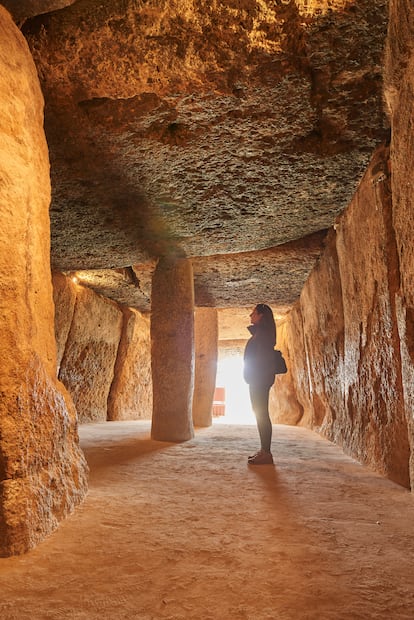

The Dolmen of Menga is located on the top of a hill that rises about 160 feet above the plain of the Guadalhorce Valley. It’s a megalithic gallery monument: 81 feet long, with a maximum width of 18.7 feet and a height that varies between eight and 11 feet. Access to the interior space is through a small, roofless atrium. It preserves three aligned pillars (although it possibly had a fourth). The 32 stones that make it up weigh about 1,140 tons. Of these, the largest — and the one that covers the back of the chamber — weighs 150 tons. This is the largest slab that was moved during the megalithic phenomenon in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-largest in Europe, only surpassed by the Great Menhir Brisé, south of Brittany, in France.

José Antonio Lozano Rodríguez, the principal author of the study and a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), explains that, to build the dolmen, “soft or moderately soft stones were used, which indicates that [the builders] had spectacular engineering knowledge. The problem was that they had to be transported without breaking, taking into account that it was a porous material. Therefore, everything was planned from the quarry, thanks to the sophisticated knowledge of engineering, geology, geometry and astronomy that its builders had.” This expert points out that the first thing that was done was to prepare a smooth pavement, so that the stones wouldn’t vibrate. This was then leveled with cross beams, so that the sleds on which they were mounted could slide easily.

Since there was no heavy machinery available to lift such a huge stone in the Neolithic period, those in charge decided to bury the megalithic building, made up of orthostates, or blocks of stones placed vertically. In this way, the convex slabs could be slid over the orthostats and pillars, meaning that the workers wouldn’t have to climb ramps.

The enormous pressure exerted by the slabs and the mound that covers it caused the engineers to design the orthostats with an inclination of between 83 and 86 degrees, so that they would rest on each other and the building would be able to join together to form a unit. “The inclination unified all the orthostates and created a homogeneous distribution of stress,” Lozano explains. To prevent the slabs from breaking in the center, pillars were placed to support them. And the upper face of the slabs, especially the heaviest slab, was given a convex shape. The slabs thus acted as relieving arches, just as occurs in medieval and modern cathedrals: this made it possible to shift the stresses towards the orthostates. “It’s the first proven use of the principle of the relieving arch, almost 6,000 years ago. It’s one of the first complex stone buildings in the history of humanity,” the researcher emphasizes.

The study adds that the engineering design and its orientation “towards the mountain of Peña de los Enamorados (”The Lovers’ Rock”) and with a solar significance” demonstrates that, in the Neolithic period, there was already scientific knowledge of extraordinary precision and inventive brilliance. The Dolmen of Menga reveals an astronomical alignment: its solar orientation means that, during the summer solstice, the left side of the inner chamber remains in shadow. Meanwhile, a large part of the right side remains illuminated.

Megaliths are structures made of large stones. They’re found in a variety of regions throughout the world and were especially popular in late-prehistoric Europe (the Neolithic period, the Copper Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age). During these eras, megalithic monumentality was widespread. Humanity’s first monumental stone constructions also contained profound social and ideological messages that were durable and visible. The longevity of large stones (unlike wood) and their visual impact on the surrounding landscapes suggest that long-term persistence was an important driver behind their construction.

The megalithic sites in the city of Antequera includes two natural formations, Lovers’ Rock and the limestone massif of El Torcal, as well as four large monuments: the aforementioned Dolmen of Menga, the Dolmen of Viera, the circular tomb of El Romeral and the recently-discovered megalithic hypogeum of Piedras Blancas, located at the foot of Lovers’ Rock.

For its time period, the Dolmen of Menga is unique for several reasons, according to the researchers from the CSIC and the universities of Alcalá, Salamanca, Seville and Granada. The use of pillars to support the gigantic cornerstones and the embedding of a large part of the building in the bedrock to achieve stability, as well as the perfect fit of the orthostates with each other, all make it a monument with “characteristics that aren’t seen in any other megalithic construction.”

A deep knowledge of the properties and location of the available rocks, as well as notions of elementary physics such as friction, activation energy, the optimal slope of a ramp, or the estimation of the center of mass or load capacity of the available rocks, make the structure unique and demonstrate the builders’ mastery of geometry, engineering and astronomy (among other disciplines). For the researchers, all of this is confirmed by “the precise alignment of the central axis of symmetry of Menga at 45 degrees, thus coinciding with the natural orientation plane of the northern cliff of the Peña de los Enamorados, to which the dolmen is oriented.”

The authors affirm that, due to the accumulation of advanced knowledge in various fields of geology, physics, mathematics and astronomy, this dolmen not only represents a feat of early engineering, but also a substantial step in the advancement of human science. “[The Dolmen of] Menga demonstrates the successful attempt to make a colossal monument that would last thousands of years,” the study concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.