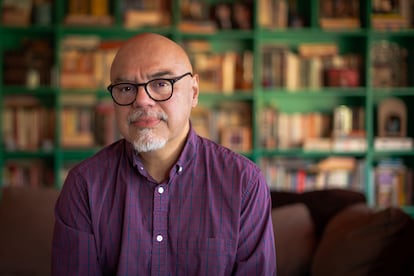

Héctor Tobar, writer and journalist: ‘The United States has made being white akin to owning property, a very valuable asset’

In ‘Our Migrant Souls’ the author reflects on the Latino experience in the U.S. and the identity process of Hispanic communities

With a long journalistic career, five books and a Pulitzer Prize behind him, Héctor Tobar’s latest project began with a simple question: what does it mean to be Latino in the United States? It was not the first time that the Los Angeles-born writer explored the identity process in a country as racialized as the U.S. He first did so in Translation Nation (2005), in which he explored the territory of Spanglish, that intangible nation made up of 35 million Spanish speakers in North America.

Tobar, 64, revisits the subject in Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino”, in which he examines decades of thought on the subject from an angle that is both ambitious and personal. A professor at the University of California, Irvine, the writer describes what he calls the “Latino experience” which, in his case, began with his father’s departure from Guatemala after the U.S.-backed 1954 military coup that ousted President Jacobo Árbenz. Tobar retraces his father’s journey, visiting his family’s village, where he was able to piece together his family tree for the first time.

“Every time I go back, I realize what I lost,” the writer says over a sandwich at the iconic Phillip The Original restaurant in downtown Los Angeles. It’s the place Tobar, an experienced Los Angeles Times journalist, chooses to talk about his new book, which won the University of Arizona’s Zócalo Award, presented June 13.

Question. Why did you write Our Migrant Souls?

Answer. I was working with a lot of young people in courses on Literary Journalism and Chicano Studies. For their finals, I asked them to tell me a story about the Latino experience in the United States. So I became familiar with a lot of stories about growing up as a Latino here. I didn’t think there had been anything written before on this experience with a literary impact equal to what James Baldwin or Ida B. Wells did with racial issues. And I wanted to go in that direction. I wanted to write something poetic.

Q. Did you also talk to your students about it?

A. Absolutely. It was a kind of recognition of them. They are living a unique moment; they are people who have lived through the experience of their parents and have a vision of what this country is. It is material that hasn’t made it into mainstream media. It’s not on Netflix. What we’re presented with are extremely romanticized or extremely violent visions of the Latino experience. So I felt the need to honor their vision and show how powerful it is. I tell my students that they are standing on enormous cultural capital.

Q. And what is your vision?

A. The United States is a mestizo country. It is assimilating the way of being, and the idiosyncrasies of the Latino communities across the country. If you go to South Dakota, Maine, Tennessee, or Oregon you will find Latino communities. Almost everyone has a Latino co-worker or their children married someone from a Latin American country. So that Latino-ness is seeping into the American way of being, which is the story of the U.S. A lot of the xenophobia is a response to that, to this supposed threat to the racial order of this country.

Q. Why do you use quotation marks when you refer to “Latino”?

A. Because the ethnic and racial terms of this country are myths; they are inventions. Latino — and this is something I learned recently — comes from an idea of Latin America linked to the mythology of French imperialism in Mexico. It’s this idea of “we are not invading you because we are Latino brothers, and we have a common cause against the Anglo-Americans.” Our idea of Latin America has its origin in the Napoleonic wars, which is absurd. And not only that, Latino implies that the essence of our collective identity is European, which completely erases our Indigenous roots and African influences.

Q. You write that “Latino” replaced other terms such as Chicano and Bracero, etc. Is it a hollow definition?

A. Those terms have always been very fluid in history. During my lifetime, I have seen the term Chicano almost die out. At the same time, I have seen the ethnogenesis of Latino. Ethnic terms can be born out of nowhere. Here in California for a while “Californio” was used to describe mulattos, Indians and Creoles. These are hollow terms. That’s why it’s ridiculous for people to spend time saying who is Latino and who is not.

Q. Maybe whites in the U.S. have specific traits in common. What traits would Latinos have in common?

Q. I thought about this a lot. The Latino term means you have a history of empire in your ancestry. It’s almost like being Jewish. When you’re Jewish, you sit down and celebrate Passover, a story of exodus and survival. That’s what being Latino means to me. At some point, you are defined by this relationship with the power of an empire. If you are Cuban, it means that the struggle between the U.S. and the former Soviet empire helped you define your relationship with an island. Before that, it was the struggle between Spain and Cuba. If you are a Texan several generations back, at some point the border crossed your path.

Q. Does this also lead to the need to decolonize histories?

A. Racial and ethnic identities are really masks that hide complex histories. I once interviewed a 90-year-old guy from South Los Angeles for a column. He was white but had led a life of crime in gangs. He was from Macedonia, with roots in the old Ottoman Empire. He moved to a part of town where everyone was from somewhere else — Canada, Ireland, Germany. On that street, everyone became white. White, in America, meant you left behind the pain of being a poor European. You are no longer a poor Italian, Pole or Jew. You are already in a white space where there is only opportunity, and no obstacles in your way. Not only that. The political and economic system gives you every advantage. This country has made being white akin to owning property, a very valuable asset. The other races were created as a contrast to being white.

Q. Latinos make up 20% of the population, but the goal of many — for example, the Latino Trumpists — is to join that white empire.

A. That has always been part of the Latino experience. In the court case that prompted integration in Orange County Schools — Mendez v. Westminter — a group of Latino families, Puerto Rican and Mexican, had seen their children separated from the rest. So they sued the school. And one of the arguments was that they should not be segregated because they were not Black.

Q. So you agree the experience has negative elements?

A. Yes, it can be negative, but magical at the same time. You have this beautiful place in your past. Here in Lynwood, there’s a mall that gives people a taste of what a small town is like. People get the idea that they come from a place more associated with nature and community. It gives them pride and a feeling of being centered and more deeply rooted. If you talk to a poor white person from a rural area, they don’t have this idea of belonging to something solid and grounded. That’s why Trumpism exists. It offers them this identity or an explanation of their status.

Q. In fact, you barely mention Trump in your book. Why is that?

A. There was no need. What’s interesting is what makes people believe in him. If you only think about Trump and his insanity, you stop thinking about the emotional reality that created him. Which is that white, as a project, is dying. It is more important to me to link our history to a 300-year history. What the Latino people are experiencing now is what the oppressed people of North America have experienced since the founding of the country. We have been treated as a crisis. It is the American way of doing business and creating wealth: attract people to come, exploit them, and then consider them parasites. They did it to the Chinese in 1870 and to Black Africans during slavery. It’s an old story. It’s important to me that Latinos know it wasn’t just us.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.