A final verse in the trenches: armed poets who died for a cause

An author reconstructs the constellation of writer-warriors of the 1930s, who fueled a burning Europe before dying in the flames

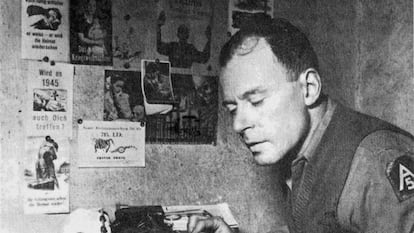

With one hand they held the pen; with the other, a gun. They were writers, but they dreamed of being warriors… or better yet, heroes.

They didn’t fear death. They were the last romantics. And, almost a century later,

Italian writer Maurizio Serra has brought many of them together in The Armed Esthete, a book about several poet-warriors who fought in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. They were the spiritual children of D’Annunzio, Kipling, Marinetti, Junger, Croce, T.E. Lawrence and other exalted writers. They were fascinated by utopias and attracted to the epic of tragedy. Due to their young age, they hadn’t fought in the trenches of World War I. They felt nostalgic for what they hadn’t experienced: they yearned for a patriotic adventure, an era of ideological overdose and fascination with banners and flags. Perhaps that’s why they began to poetize fascism, communism and war. Many would take up arms in the name of various causes.

Maurizio Serra – the biographer of several Italian poets – explains that the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) constituted an essential milestone to understanding the profound dimension reached by the armed esthetes of Europe. To understand the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry – already in his forties and tired of not being able to lend his strength to his country – you must understand what motivated him to fly with the French Air Force. To understand the poems by the British writer W. H Auden, one must grasp his obsession with honor. And, to enter the mind of the Italian poet Lauro de Bosis, one must recognize his anti-facism, which made him capable of writing a text titled Story of My Death, shortly before fulfilling the mystical call of sacrifice.

Likewise, Serra finds it essential to examine the communist soul of the English novelist Christopher Caudwell and his early death in Spain with the International Brigades, or the leanings of Simone Weil (so intellectual with her glasses), who left Paris to fight the fascists. He also dives into why the German writer Klaus Mann – frightened by Nazism – joined the Anti-Fascist Front in the Spanish Civil War, before enlisting in the US Army to take part in the liberation of Italy.

The embryo of many of these stories are found in the battle between the Republicans and the Nationalists in the lead-up to World War II. First, says Maurizio Serra, because it was probably the last romantic conflict in Europe. Secondly, because this romanticism gave a prominent role to intellectuals, to the point that the Spanish conflict was baptized as “the war of the intellectuals.” And, finally, because the Spanish Civil War revealed the need for many writers to take action. To leave the libraries, the newsrooms and the cafes: to go protest in the squares, or fight on the frontlines, abandoning the ambiguity that was typical of intellectuals.

“Spain,” the author of the book explains to EL PAÍS, “represented a fundamental crossroads. A phenomenon with no equivalent in the 20th century, neither before nor after. This shows that Spain – alien to the two world wars – was nevertheless a protagonist in the history and sensitivities of [the 20th century].”

It’s impossible to summarize a 500-page book, whose index compiles more than 800 names. There are excerpts from novels, fragments of poems, political connections, human stories… all the threads of an intellectual spiderweb that trapped many authors. Some died on the frontlines, while others committed suicide afterwards, or spent the rest of their lives in exile. Serra’s book paints a portrait of a lost generation that inflamed Europe, creating a veritable cultural bonfire. The Italian explains that, during the interwar period, “culture aroused passions that were, in turn, a reflection of its power to disrupt. The culture didn’t [opt for reconciliation] – it provoked reflections from some and counter-reflections from others. But many ended up [engaging in inappropriate actions] which had disastrous results.”

The catastrophe tore apart both Europe and the poets, who shared a rejection of a sedentary and bourgeois life. Their mystical vein was inflamed; their sense of honor was very pronounced. They wanted to show the public that they also knew how to fight… that they could sacrifice themselves just like the common people. All very romantic. However, reality contradicted them time and time again.

The English writer Frank Jellinek spoke about how “Barcelona was packed with thoughtful intellectuals who had no idea [about] what was happening and had no qualifications at all [regarding how to use] a machine gun or a typewriter.” The author of The Armed Esthete asks a similar question: “Spain, the Republic, freedom, the revolution… did they really need [the intellectual’s] blood, his often weak muscles, his often uncertain aim, his enthusiasm and his spirit of sacrifice, [all of which] rarely compensated for his poor aptitude for military discipline and combat?”

Perhaps the intellectuals’ greatest contribution to the war wasn’t in the trenches, but in the legacy left behind by the literature of testimony. An investigation has calculated that the 2,300 British combatants who fought in the Spanish Civil War wrote and published a total of 730 literary works, mostly war diaries… one book per every three combatants. They wanted to remember everything, while also reminding others about their feats, either in a romantic way, or in an authentic, crude way.

This latter realistic feeling was condensed in a phrase that summarized the destiny of that generation of young poets who carried rifles on their shoulders: “Where are the war poets? Killed in Spain.” This emphasizes the failure of the armed esthetes. One of them – Esmond Romilly, an anti-fascist journalist (and Churchill’s nephew) – noted, upon his arrival in Spain: “I came here because they told me there was a revolution and, instead, I found a full-blown war! I came here to fight against the fascist executioners… not to be turned into an idiot dressed as a military man.” Esmond survived the battle of Boadilla del Monte and its dense and dangerous fog. And then, a few years later, he died in World War II. He was only 23-years-old.

Incomparable to the present

In the opinion of Maurizio Serra – a member of the French Academy and winner of the Prix Goncourt in the category of Biography – it’s impossible to compare the role of intellectuals in those feverish times with the current era, which is also marked by wars and ideological ardor. “Comparisons are always difficult and incomplete. They belong more to sociology than to the history of ideas, which is my field. I don’t think it makes much sense to talk about armed esthetes today.”

What made them do it? Virginia Woolf, who lost her favorite nephew – the poet and critic Julian Bell – in the Spanish Civil War tried to answer that question. Why did so many intellectuals risk and lose their lives in that decade? “I think there’s a fever in the blood of the younger ones that we can’t understand,” Woolf said.

But it wasn’t in the blood. It flowed, rather, in ideas and emotions, in the longing for a regenerated humanity – the new man – and its absolute dedication to a goal that would give meaning to life. There wasn’t a right-wing or left-wing in that; it wasn’t a question of Malapartes or Malraux. There was shared messianism. Culture didn’t manage to inoculate Europe from horrors. There was poetry after Auschwitz, just as there was poetry before Auschwitz, to harken back to the horrors that preceded it. There were poets who, in the 1930s, believed that it was no longer sufficient to just publish – they wanted to fight in the mud of the prosaic trench. They were looking for the absolute and they lost everything, in a bitter final verse.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.