New research suggests oldest diving device in history may be early 17th-century Spanish invention

An investigation has concluded that a large copper piece recovered from the galleon ‘Santa Margarita’, shipwrecked in 1622, is the upper part of a submersible diving bell, predating Edmond Halley’s machine by seven decades

Sometimes the most surprising archaeological finds do not require long and costly excavations, but rather a special ability to look at something that is already in plain sight from another angle. For 40 years it was thought that one of the pieces found on the Spanish galleon Santa Margarita, discovered in 1980 by the famous American treasure hunter Mel Fisher (1922-1998), was nothing more than a large copper pot the crew used to boil fish. Now, some of the archaeologists who participated in that expedition have dedicated themselves to investigating the matter from another point of view. Their conclusion is that this strange piece of copper — 147 cm in diameter and dotted with rivets — is the upper part of a diving bell; perhaps the oldest submersible device ever discovered for which there is physical proof. The results of this research have been published in the latest issue of Wreckwatch magazine, which specializes in underwater archaeology and technology. If the researchers’ hypothesis proves to be correct, the discovery would place Spain among the pioneering nations in the history of diving, which until now has been almost exclusively attributed to British inventors.

Since its discovery, the copper piece has been on display at Mel Fischer’s museums in Florida — first in Key West and then in Sebastian — as part of the remains of the Santa Margarita, a galleon of the Fleet of the Indies that was wrecked in 1622 along with the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and the Nuestra Señora del Rosario in a devastating hurricane in the Florida Keys. The treasure the convoy was carrying was the cause of a years-long legal dispute that pitted Spain against Fisher and ended with the victory of the treasure hunter. Spanish officials still angrily point out the number of photos Fisher took of himself displaying gold medallions hanging from his neck. But that is another story.

In any case, the copper bell in question, according to researchers, would not have traveled in that convoy, but on one of the salvage ships sent to recover the cargo. The promoter of that expedition was the Spanish soldier and politician Francisco Núñez Melián, resident in Havana and treasurer of the Windward Islands at the time of the shipwreck. According to a document dated 1630 and consulted by the researchers, Melián was aware of the lost riches and obtained royal permission to send a frigate to the area of the shipwreck in August 1625, piloted by a certain Francisco de la Luz. The fate of that vessel, whose name remains unknown, is still a mystery, but everything suggests that it was lost off the coast of Florida with the diving equipment it was carrying to attempt to extract the precious cargo.

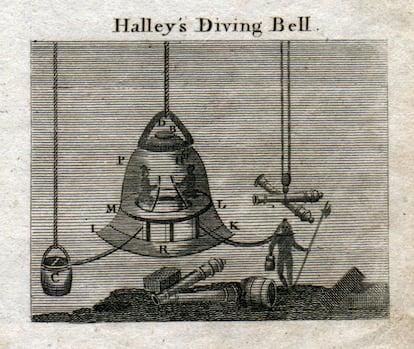

There is evidence that Núñez Melián launched a second expedition that returned to the area that same winter. In the 1630 document, it is noted that a new bronze diving bell was commissioned, weighing 700 pounds, standing 1.21 meters high and measuring 91 centimeters in diameter. That bell was probably built according to the 1606 prototypes designed by Jerónimo de Ayanz, which had been tested in the Pisuerga River in northern Spain. Air pressure maintained an air-filled chamber inside the bell. Fresh air was obtained through a tube connected to the surface that allowed two crew members to descend and supply air to another diver on the sea floor.

The second expedition proved successful and Núñez Melián was able to recover 350 silver ingots, 74,700 pesos in reals and eight cannons. Over the following two years, he managed to recover more of the sunken wealth. As a reward, and after much petitioning, Philip IV appointed him governor of Venezuela, a post he held from 1630 to 1637. He died in 1644 when he fell off his horse during a military parade.

The bulk of the treasure that Núñez Melián searched for would not be found until centuries later, when Fisher and his team found the remains of the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and the Santa Margarita. Among their discoveries was the huge copper piece, which they took to be a pan for stewing fish. The archaeologists’ recent deduction is overwhelmingly logical: if Núñez Melián sent a second expedition, it is because the diving equipment was lost on the first. The pan was actually the upper part of a diving bell, similar to the one used on the second trip, but much larger and probably made of a different material. Had it been made of bronze or copper, it would not have escaped the magnetometer deployed on underwater wreck-finding expeditions. “For that reason, I’m inclined to think that the first bell was made of wood with a copper dome fitting,” says Sean Kingsley, one of the researchers and founder of Wreckwatch magazine.

Kingsley, who holds a Ph.D. from Oxford University and has explored some 350 wrecks, hands most of the credit for identifying the diving bell to Jim Sinclair and Corey Malcom, two of the experts on Fisher’s team who conducted the exploration of the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita wrecks. Neither of them had been convinced by the cooking pan theory.

During the colonial era, Spain was a major naval power that conducted around 17,000 return voyages to the Americas, almost all of them loaded with gold and silver coins bound for the coasts of Andalusia in southern Spain. Some estimates indicate that 16% of those ships were lost due to bad weather. It is therefore logical to assume Spain made a virtue out of necessity and occupied a place in the history of submarine technology, even if until now it has been little recognized. Edmond Halley — the discoverer of Halley’s comet — has generally been credited as the inventor of the diving bell, in 1691, and the forerunner of modern diving.

In the article in Wreckwatch magazine, whose latest issue is devoted to underwater technology, Sinclair and Kingsley walk through other human attempts to breathe underwater. “Going into inner space — the depths of the sea — was for a long time one of the great tests of mankind,” says Kingsley. “As the Titan tragedy shows, we have not yet mastered the deep. It’s tough and dangerous. Despite all the many drawings of historic diving bells that exist, there is not a single trace of a real-life machine. That’s why the Margarita bell is the rarest technological treasure. One big question remains to be solved: where was it made and what did the whole device look like? A lot of research remains to be done.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.