‘I could’ve been more famous, but I wasn’t willing to do things I didn’t want to do’: the three deaths and resurrections of Michael Keaton

The 1980s Batman is back, co-starring in ‘The Flash’ and closing the circle on a career of strange and unpredictable roles, as well as celebrated and forgotten successes

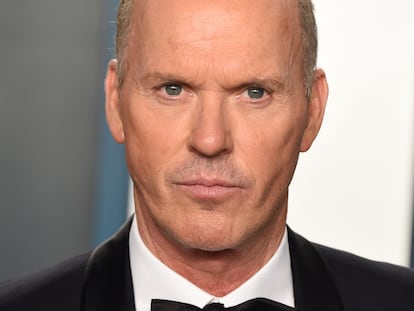

That most Americans believe Michael Keaton (Pennsylvania, 71 years old) was “the best Batman ever” will come as a surprise to those who remember the controversy his casting provoked thirty years ago. Fans wanted a canonical hero in the style of Schwarzenegger, not a tacky goofball they associated with zany comedies like Beetlejuice (1988) and Mr. Mom (1983). They didn’t consider Keaton “masculine enough” to play the imposing Bruce Wayne or his superhuman alter-ego. But now, the actor who once turned down $15 million to play Batman a third time, who often chose the most unexpected of roles, who parodied himself in Birdman (2014) and dazzled audiences in the exceptional TV series Dopesick (2021), has emerged as a popular and critical favorite in the new movie, The Flash (2023), where he once again speaks the phrase that provoked such skepticism decades back, and now provokes only affection: “I’m Batman.”

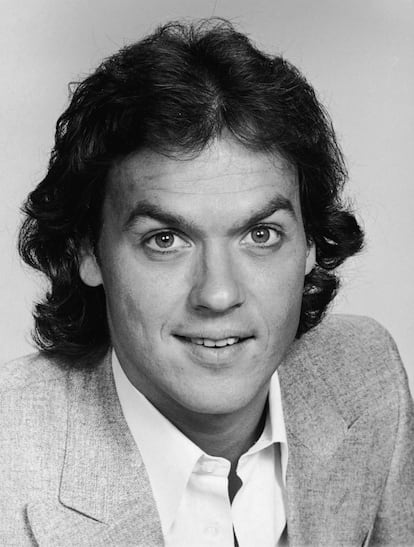

Michael Keaton hit his first stumbling block in Hollywood when the Screen Actors Guild broke the news that his real name, Michael Douglas, was already taken by another actor. As Keaton tells it, there was no great inspiration behind his choice of new last name — he didn’t choose it because of Buster Keaton, it was simply the first name that came to mind and sounded good. He grew up with seven siblings in a working-class family, and before becoming an actor he studied to be a journalist, a background that would serve him well for his performances in two films: The Paper (1994) and the Oscar-award-winning Spotlight (2015). But he would find his true calling through his experience in stand-up comedy.

Talent agent Harry Colomby discovered Keaton during one of his stand-up performances in West Hollywood. “What I saw in Michael was something original,” he said. “I also saw charisma onstage.” Colomby managed to secure Keaton a starring role in Working Stiffs (1979), a sitcom about two brothers (Keaton and James Belushi) who work as janitors. The show didn’t even last a full season, but it put Keaton on the map, and swept him along to his next role in Night Shift (1982), where he plays a character who tries to turn a morgue into a brothel — a role that, in a way, would come to define his career, as an actor drawn to unconventional performances.

Keaton’s first success was Mr. Mom, a cliché-ridden film about a man who does housework: it could have easily been insufferable, but Keaton’s performance and John Hughes’ script managed to save the film. After two successful roles, Keaton’s career seemed fully launched, but a couple of performances in films that didn’t quite live up to expectations landed him back at the end of the line. Hollywood waits for no one. His excitement at being chosen as the star in the romance The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) was short-lived. After the first few days of filming, Woody Allen decided that Keaton was too “modern” for the role, that he didn’t fit the dapper classic heartthrob character he was looking for, and replaced him with Jeff Daniels. “Michael Keaton was right out of the 1980s, not the 1930s. People are always trying to figure if it was more than that, but that’s all it was,” Allen would later clarify.

The executives at Fox would not return Keaton’s calls, and eventually let his contract expire. He seemed doomed to fade into the endless list of actors who fill the ranks of supporting cast, but he had two things working in his favor: he was very talented, and now, suddenly, he was very cheap to hire. That combination proved irresistible to Tim Burton, a young, eccentric director whose only notable work to date was the unclassifiable Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985), a rare television gem, propelled by the singular performance of Paul Reubens and grossing some $40 million. At the time, Burton was preparing a small project about a mischievous bio-exorcist named Beetlejuice. His first choice to play the character was Rat Pack member Sammy Davis Jr., but producer David Geffen suggested Michael Keaton. The film was a critical and commercial success that skyrocketed the actor’s popularity, despite the fact that Keaton appeared on screen for less than 20 total minutes. That same year, he played an addict in the drama Clean and Sober (1988), proving that he could be more than just the perfect comedy lead.

Tim Burton had no doubt that Keaton would be his perfect Batman. But the superhero’s fans disagreed. Warner received more than 50,000 letters protesting Keaton’s casting. In a world that did not yet know the all-consuming global power of social media as force for directing collective hate, these fans took the time to compose letters, buy envelopes, and purchase stamps in an effort to communicate their opposition to the casting of their cartoon hero. They feared that Keaton’s past would turn Batman into a parody, and they criticized his short height (5′7″) and his not-very-athletic demeanor. The Wall Street Journal carried the controversy to its front page: “Keaton has a receding hairline and a less-than-heroic chin.” And the paper quoted the opinion of one fan who argued, “If you saw him in an alley wearing a bat suit, you would laugh, not run in fear.”

Burton saw before anyone else that Keaton’s circumflex eyebrows and piercing gaze captured the tormented soul of the character who, as a child, witnessed the murder of his own parents. Keaton was not only a good Batman, he was a great Bruce Wayne. “Michael Keaton is basically an ordinary guy, a regular human being,” the director said. “I thought it would be much more interesting to take someone like that and make him into Batman. I met with a number of very good, square-jawed actors, but the bottom line was that I just couldn’t see any of them putting on a bat suit.”

The angriest critics ate their words as they watched the film rack up $400 million at the box office when it was released in 1989. Batman mania was everywhere: Prince’s theme song played on every radio station and the black and yellow logo was plastered on every product imaginable. The dark and majestic depiction of Gotham captivated even the purest fans. Everything worked. Especially Keaton, a Batman capable of resisting the force of nature that was Jack Nicholson playing the Joker.

As with any successful Hollywood blockbuster, the inevitable sequel followed. In Batman Returns (1992), Burton became more Burton than ever, both for better (Pfeiffer’s Catwoman) and for worse: the army of penguins led by Danny de Vito overshadowed Batman, and scared children. This time it was not the fans who complained, but the parents of terrified kids. Warner wanted a family-friendly saga, so they ditched Burton and set their sights on Joel Schumacher, another young director who had managed to pack the theaters with teenagers eager to see his hit horror flic, The Lost Boys (1987). Nearly 30 years later, Keaton and Burton teamed up again for the live-action adaptation of Dumbo (2019). “What Tim did changed everything.” Keaton told The Hollywood Reporter. “Everything you see now started with him.

Many expected Keaton to exploit his new heroic image as Batman, but once again, he opted for the unpredictable. He put his manic gaze to good use in his role as the tenant who intimidates Melanie Griffith and Matthew Modine in Pacific Heights (1990), played a dying father in the moving drama, My Life (1993), stepped back from his usual leading role in Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing (1993), and did the same in Jackie Brown (1997) and Out of Sight (1998), both adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard. Once again, Keaton appeared to find himself ostracized and off the map.

“I guess it wasn’t the obvious way to go if you wanted to carry on being a big star,” Keaton confessed in a 2014 interview with The Independent. “It’s great to make your own choices, but there’s a price to pay. I could’ve made more money or been more famous. I could be the current groovy guy. You don’t want to lose your status but I was never willing to preserve it by doing things I didn’t want to do.”

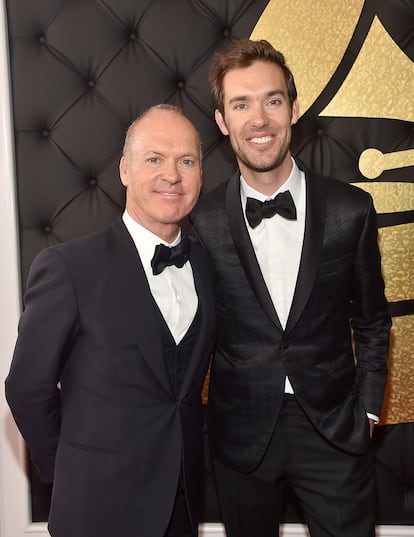

Keaton was fine with losing his status and his chance at greater fame. He retired to his Montana ranch to raise his son. “I gave up more than a few movies when my kid was young because I always wanted to be a dad,” he said. Keaton likes to keep his private life private: he had a relationship with Courteney Cox (Friends), and was married for eight years to actress Caroline McWilliams, with whom he had a son, Sean.

Keaton was a lost star of Hollywood when he received a script for Birdman (2014). The plot centered on an actor celebrated for playing a superhero who turns his career around — a role that, despite director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s insistence that the film reflects his own midlife crisis, felt more like a biopic of Keaton himself. His walk through Times Square in his underwear became the most talked-about scene of the season, and put him in the race for an Oscar. He didn’t win, but he received his first and only nomination of his career to date. The following year, he joined the cast of another box-office hit, Spotlight.

While the little golden statue continues to elude him, Keaton has won plenty of accolades for his performance in the television series Dopesick. His role as an Appalachian doctor who unwittingly places himself at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic won him a Screen Actors Guild Award, a Golden Globe and an Emmy. In his acceptance speech for the latter he vindicated himself: “I’ve had some doubters. You know what? We’re cool. But I also had those people for all these years when times were up who were the true believers.” Even so, his role in Dopesick could have been his second most memorable television performance: 20 years earlier, Keaton had turned down the role of Jack Shephard on Lost (2004-2010).

When DC Comics asked him to put the bat suit back on (first in the unreleased Batgirl, which was cancelled in post-production, then in The Flash), he didn’t understand the concept of the multiverse, and how it could justify sharing a role with Ben Affleck for the same character in the same storyline. “They had to explain that to me several times,” he said. Despite his reservations, he agreed. “Frankly, in the back of my head, I always thought, ‘I bet I could go back and nail that motherfucker.’” And, according to critics and fans, he has.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.