A kilo of cannabis and a mind-blowing interview: When Bob Marley landed in Spain’s Ibiza

It’s been 50 years since the release of ‘Catch A Fire,’ the album that introduced the king of reggae to the world. Shortly after, in 1978, he traveled to Spain for the first time, in a visit that gave rise to surreal moments

When Catch a Fire was released in April 1973, Bob Marley (1945-1981) already had a 10-year-long career and multiple recordings under his belt, although the latter were all credited to his band, The Wailers. They were local idols but garnered little attention outside their native Jamaica. In the 1970s, Chris Blackwell signed them to his label, Island Records, and plotted their course to world stardom. The release of Catch a Fire was the initial step. “It was the first album in which the artistry and charisma of Marley and The Wailers – Peter Tosh and Neville “Bunny Wailer” Livingston – combined with the commercial vision of Blackwell, who began to act on the roots, rock, reggae idea he had conceived for turning The Wailers’ sound into something that could connect with many more people,” says Dr. David Decker Vilches, a reggae expert. Island Records aggressively promoted the album, and the tour had several notable milestones: in New Jersey, Marley opened for then-newcomer Bruce Springsteen and, later, for the entire Sly & The Family Stone tour. Well, not exactly: on the fourth tour date, the promoters decided to remove the band from the lineup because, some say, they were overshadowing the main act.

Catch A Fire was the first album that Marley recorded professionally in a studio, under the same conditions as rock stars of the day. His style of incorporating elements of rock, blues, funk and soul paved the way for his international success. And Marley’s lyrics were also fundamental to his appeal; his songs had a very powerful message that already showed why he was going to catch on globally: “They called him the Black Bob Dylan for a reason,” says Carlos Monty, a cultural journalist and the author of the book Bob Marley: Positive Vibrations. “His message of emancipation for the oppressed of the world, of love and positive vibrations as the only way to live, and respect for roots and nature, transcends his Jamaican and Rastafarian localism and appeals to the universal values of peace and mutual respect with which any generation in any part of the world identifies […] Without trying to, Marley connected with the dispossessed, and his extraordinary attitude, at once revolutionary and spiritual, made him the first global icon to emerge from the so-called third world. There is no place on the planet where people don’t know him.”

Ganja in Ibiza

During Spain’s transition from the Franco dictatorship to democracy, not many people knew about Bob Marley’s legendary status. Today, his first concert on the Spanish island of Ibiza on June 28, 1978, is remembered as a historic event, but at the time, the local population did not see it that way. “At that time, he was not sufficiently understood, and, somehow, he was pigeonholed as a hippie, at a time when the hippies’ day had long passed, and by the stereotype of sun-palms-weed-good vibes, which has done so much damage to reggae,” explains Dr. Decker.

That performance in Spain occurred thanks to a group of British promoters based on the island, and they paid a considerable sum for the Jamaican to start his European tour for the album Kaya in Ibiza. They also faithfully met the artist’s demands: a kilo of Jamaican ganja (cannabis), another kilo of Jamaican honey and 10 kilos of white fish. The concert tickets were costly, and the arena was not full, even though much of the audience entered without paying. “There was a mess with the tickets, some were sold two or more times, and many people snuck in,” recalls Mariano Planells, a Spanish writer and journalist who attended the event. “By then, there weren’t many hippies, but a band of mixed race people with dreadlocks didn’t attract much attention, either. [They were of interest] only to the people who were waiting for them at the airport.”

The entourage that received them at the airport included music journalists Ángel Casas and Carlos Tena. They were the first to welcome Marley to Spain and conducted an interview with him on Spanish television. Photographer Francesc Fábregas joined them. Fábregas took photos for the magazine Vibraciones and followed Marley’s entire journey through Spain’s Balearic Islands. The trip was much easier than the rock star tours to which he was accustomed. “It was all very provincial, very primitive, I don’t even know if they went through customs, there was very little control.”

That laidback attitude can be seen in the interview, in which Bob Marley appears smoking. “Maybe it was the ganja, or perhaps the nervousness of finding ourselves in front of a star of Bob’s caliber, or maybe the patois-inflected English of the author of No Woman, No Cry or our own [English], but the fact is that we didn’t understand each other at all,” Carlos Tena recalls on his blog. “I asked him about an incident that had apparently got him shot in an arm, to which he replied that it never happened. An hour later, when the cameras had finished rolling, he showed me a scar on his left arm and said: ‘Look, look at the bullet I took a few years ago during a scuffle in Kingston,’” the journalist recounts.

But despite the shared sense of disaster, Fábregas those moments are etched in his memory. “Of the many thousands of concerts I’ve been to, he’s the one I remember most fondly. What he transmitted was something spectacular. His feeling, his way of moving like a contemporary dancer. It was a special thing that caught [your attention and] hypnotized you,” says Fábregas.

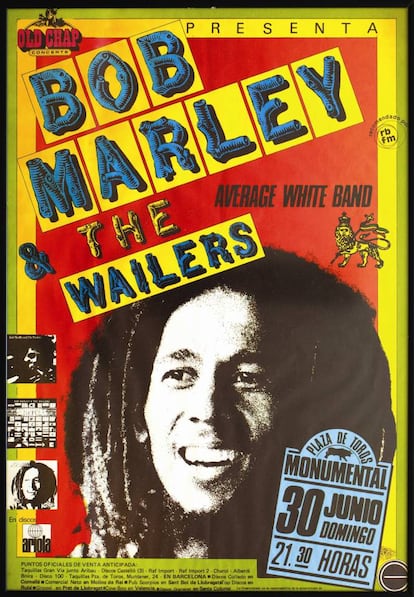

Two years later, on June 30, 1980, Marley performed in Barcelona. He was scheduled to perform in Madrid as well, but the government forbade it due to an incident two days earlier at a Lou Reed concert. Almost 20,000 people went to Barcelona’s La Monumental bullring. Fábregas photographed Marley from the pit again, but it wasn’t the same: “We were already in show business, everything was much more professional and restrictive, and I don’t even remember how the concert went. The one in Ibiza, however, I will always carry with me, I don’t even need the photos to remember it.” Just 11 months after his visit to Barcelona, Marley died from a malignant melanoma under his toenail that he had refused to treat. He was 36 years old.

Rastaman in 2023: Revisiting the icon

Forty years after his death, Bob Marley is still a brand and a money-making machine. According to Forbes magazine’s lists from the last decade, he is usually among the top five highest grossing dead celebrities. Among musicians, he is surpassed only by Michael Jackson and Elvis Presley. His Facebook profile has 67 million followers (twice as many as The Beatles), and on Spotify, Marley attracts 15 million listeners each month. His website, which is owned by his heirs, is dominated by marketing, including an ad for a video game, casting for a future biopic and deluxe reissues of his discography.

Beyond his posthumous earnings, Marley continues to have an enormous cultural impact. In Spain, for instance, the Rototom Sunsplash festival dedicates tributes of all kinds to him every year, and his influence has expanded through constant tours by his widow, Rita; his sons, Ziggy and Damien; and even The Wailers, who remain active. “Since 1981, [there have been many] tributes in all languages and from all around the world, one after another,″ Carlos Monty explains. “A few days ago, the Grammy Award for best reggae album went to The Kalling, by the innovative artist Kabaka Pyramid, which was produced by two of Marley’s sons, Damian and Stephen, demonstrating that the relevance of [Bob Marley’s] dynasty.”

But despite his popularity, Marley had his share of contradictions and controversies. It seems inconsistent that a man who symbolized peace and social justice bought the Rastafarian idea that Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (who was criticized by human rights organizations) was the reincarnation of God. And Rita Marley’s 2005 autobiography, No Woman, No Cry, offered a critical and unsparing view of the singer: he was abusive in their marriage, polygamous and fathered illegitimate children with several women around the world. Does this cast a pall over the personality, or make him a target for so-called cancel culture?

“It would be absurd and counterproductive to eliminate parts of music history because [someone’s] values do not mesh with current [mores]. But, precisely for that reason, revisiting the character and the work seems necessary and positive to me,” notes musicologist Laura Viñuela. Historical context can lead to a better understanding of his actions, but we also have to consider that Marley traveled a lot around the world and, since the late 1960s, the second feminist wave was in full swing with slogans like “The personal is political.” Moreover, within the civil rights movement, Black feminism was also flourishing at the time. Bob Marley could have been interested in this part of the struggle against social injustice because it was also part of his context.

“The first thing to clarify is that Jamaica, with its African heritage and the Rastafari religious movement, has cultures of oral tradition, not written ones like we are used to in the white West. There is a lot of fabrication. That’s why the same story is repeated by its protagonists in a thousand different ways, depending on who and when you ask,” argues Carlos Monty. “The things that Rita Marley or any of her relatives may say or publish now about someone who is no longer here to defend himself, in addition to being opportunistic, do not jibe with the proven fact that she was the one who, for much of her life, chose her husband’s multiple mistresses when he was on tour. Nor does it fit the greedy way in which she hoarded the inheritance.” The journalist points out that “a Eurocentric analysis of foreign cultural figures without the appropriate context would be yet another example of white supremacy. We have to understand that a working-class hero like him necessarily had to be fierce to defend his own and survive in a hostile environment; that explains many of the accusations that can be made against him from the comfort of the European middle class.”

“What personality, or even what person, does not have a good and bad side? In Marley’s case, it is clear that his genius and legacy far outweigh those flaws, which we cannot deny if we want to be objective,” adds Dr. Decker. “The thing about revisiting figures of this type is that, in the end, we don’t want to lose the illusion that they were something pure. And learning that they were flesh-and-blood people who did things we don’t really like makes us feel betrayed. The music we love says a lot about who we are and is part of our emotional autobiography as well, so there is a tendency to protect artists. Ultimately, it is a way of protecting ourselves,” Laura Viñuela argues.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.