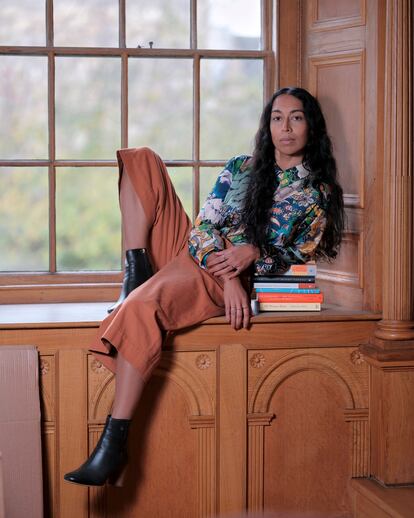

Amia Srinivasan, philosopher: ‘We must create a sexual culture that destabilizes the notion of hierarchy’

The most intimate of acts is in fact a public matter, states the Oxford scholar in her book ‘The Right to Sex.’ She advocates for a feminism at the intersection of gender, class and race

To talk with Amia Srinivasan is to be exposed to a dazzling, incessant stream of wisdom that puts your prejudices in a tight spot and arouses your mind with provocative notions and unexpected ideas. The daughter of an investment banker and a classical dancer, both of Indian origin and educated in Hinduism, her life journey took her around half the world — Bahrain, New York, Taiwan, London — and pushed her towards analytical philosophy, which she studied at Yale and at Oxford, to find a way to explain herself and her place in the world; this she found in feminism, which she has studied in depth in order to be able to move back and forth between each of its historical stages and define the coherence of a political struggle that never ends.

In 2019, after an extremely rigorous examination, she obtained the Chichele Professorship (so named in honor of founder Henry Chichele) of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College at the University of Oxford. That prized role was previously held by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin; Srinivasan is the first non-white woman – as well as the youngest person – to ever achieve that academic position.

Srinivasan received EL PAÍS in her university refuge, a room with hardwood walls, a fireplace, Chesterfield armchairs, leaded windows that overlook one of the cloisters of the building and books, lots of books, on shelves, in boxes, on the study table.

An overwhelming, high-profile woman has burst into a club of circumspect gentlemen in tweed jackets and bow ties that used to be supported by the full weight of classical Western philosophy. With an agile, poignant, accurate and intelligent style of writing, her book The Right to Sex has aroused an enthusiasm and an interest in feminist literature that had not been seen for a long time. As an essayist, Srinivasan covers many other issues, but as she herself points out, paraphrasing Michèle Le Dœuff, “when you’re a woman and a philosopher, it’s useful to have feminism to be able to understand what is happening to you.”

Question. What is feminism?

Answer. Feminism isn’t an idea or a theory or a belief. Sometimes people say it’s the belief that women and men should be equal. That leaves open lots of questions. Women should be equal to… which men? Because men themselves aren’t equal. And equal in what way? Materially? Economically? Politically? Legally? You can also believe that women and men should be equal, but not be struggling for it. And so what I want to say is that feminism should be first and foremost understood as a political struggle, as a movement, or really a set of movements that happen across the world at different moments in history, that ebb and flow and have different kinds of commitments. And most of all, I think it’s a movement about bringing closer to reality a set of as yet unimagined possibilities.

Q. The new feminism has established consent as a fundamental criterion in sexual relations.

A. This is such an important question. I mean, we get to thinking about the permissibility, the legal permissibility, of sex, in terms of consent; it’s a great feminist advance on the traditional historical ways of thinking about it, where force was the definition of the criteria of sexual assault. And of course, as we know, there are cases where force isn’t used; you can think about vulnerable people, young children, but nonetheless, there’s obviously a violation. So in that sense, moving towards consent is a victory.

Q. But...

A. But it poses various kinds of problems. I mean, in a court of law you need very clear criteria, and it needs to be operationalizable, and it has to be criteria that you can actually apply and use to make decisions to distinguish between, you know, legal and illegal cases of sex. But once we get outside of the law court, and we’re thinking about actual interpersonal relations, we all know it’s much more complicated than that. There are cases in which someone will not only not say no, not resist, but will actually say yes, but that yes, itself, is the product of a certain set of social expectations which the other person might not even have. You see this, I think, especially with young women, young adult women.

I think sometimes feminists are guilty of endorsing forms of overregulation, because what they’re trying to do is to use the law – or proxies for the law, like university regulations – to try to get people to act as we would in an ideally moral case. And so one of the major themes in the book is the limits of the law in our ability to change culture, and alternative ways that we can change culture.

Q. In certain societies, there are sectors that do not understand the overly combative tone of feminism. They believe they perceive an unnecessary aggressiveness.

A. The point of a political movement isn’t always to simply convince opponents, right? There’s also a value, or can be a value, in expressing and experiencing certain kinds of seemingly extreme political emotions as a way of mobilizing groups. An obvious example of this is the case of Malcolm X and black power in the US, you know, extremely off-putting to an opposition and scary to the white, male, cultural mainstream. We can say that it was quite effective because it made Martin Luther King, who was himself very much a radical and very much an economic radical, seem quite moderate.

We should think about the anger that you correctly identify as sometimes central to feminist movements in the same way. Yes, it can be off-putting, but it can also be galvanizing. And also, sometimes, it can be persuasive. Sometimes people do things because they’re scared of not doing it right. Scared of what will happen, and it can, by contrast, make certain demands seem quite moderate and sensible. And the final thing I’ll say about anger is, even when it is counterproductive, it’s sometimes still the right emotion to feel.

Q. One of your essays, motivated by the appearance of the incel movement [involuntary celibacy: online forums of men who are angry about being sexually ignored], raises a provocative debate: is there a right to sex? What happens to all those to whom it is denied?

A. This is incredibly well documented, the way in which people of certain races are effectively discriminated against on dating apps. We also all know that women beyond a certain age are no longer considered desirable to men, even of their same age, this sort of thing. The sexual marketplace is organized by a hierarchy of desirability along axes of race, gender, disability status and so on. And so what do we do? Although it’s worth pointing out that some feminists in the 1970s experimented with this sort of thing. They would enforce celibacy among the women in their group, or require them to be political lesbians, to no longer have relations with men. Those projects always go badly. I think what I would like is sort of two things. One is for us to kind of create a sexual culture that destabilizes the notion of hierarchy. And what I want to do is remind people of those moments that I think most of us have experienced at some point or another, where we find ourselves drawn to (whether sexually, romantically or just as a friend) someone that politics tells us we shouldn’t be drawn to, someone who has the wrong body shape, or the wrong race, or the wrong background, or the wrong class. I think most of us have had those experiences.

Q. Is it a matter of reeducating our desire, then?

A. I don’t mean something like engaging in a kind of practice of self-discipline, but rather, you know, critically reminding ourselves of those moments when we felt something that we then just denied. That’s an experience that’s very familiar to any queer person, right? Because most queer people have grown up with the experience of having desires that their politics, their society tells them not to, and then they silenced them. And so that act of remembering the fullness of one’s desires and affinities, I think it’s a good thing to do.

Q. There is an incipient battle between new and traditional feminism, regarding trans women, that confuses and worries many people.

A. Just as women entering the workforce or gay marriage constitutes a kind of threat to traditional life, so do trans people. They disrupt the very system of gender and sexuality and identity that I think forms the basis of the traditional, patriarchal worldview. And I also think that trans people speak to an anxiety that lots of us have, even people who [identify themselves] as just women or men, an anxiety we all actually have about our relationship to sex and gender. We have dreams where we have sex with the wrong kinds of people, the wrong kinds of bodies, the wrong kind of desire; in order to enter into mainstream social and political life, all of that needs to be repressed.

What I want to say to those feminists who are resistant to trans people, is to diagnose the kind of continuities that exist between cis people [those who identify themselves with the gender they were assigned at birth] and trans people, and begin from those places of continuity. Of course, there are lots of specific questions about policy, but in a way, I think there’s panics around bathrooms, or puberty blockers, that take us beyond the more fundamental conversation we need to be having first, which is: how sure are you that you really are a man? And how sure am I that I’m really a woman? And what does it even mean to really be that?

Q. What is behind the talk of false accusations? Is it a problem? An unintended effect?

A. It’s very hard to get good statistics on this, but statistically, in the US, for example, when you look at the history of exoneration, people who’ve been convicted for sexual assault and then later get exonerated – usually because of DNA evidence – Black men are massively disproportionately represented in that population. To be fair, I mean, Black men are massively disproportionately represented, you know, for all forms of exoneration. We should be talking about the failures of the legal system, when it comes to all crime. But I actually want to spend time focusing on and taking seriously the idea that it’s a terrible thing to be falsely accused of rape. It is a terrible thing. And it cannot be dismissed. And in part because it has something in common with the experience that so many rape victims have of not being believed. So both male victims of false rape accusations and female victims of rape are often facing this kind of conspiracy, this epistemic conspiracy of disbelief. But I want us to ask the question: who are the men who must suffer from it? And the answer is very often working class men and men of color.

Q. Seen with a certain logic, the 2008 crisis has a lot to do with the rebirth of feminism.

A. Yes, absolutely. I think there are sort of two lines one can draw from the 2008 crisis to the resurgence of feminism. One line is, precisely as you’ve said, that generalized economic crisis always particularly hurts certain groups and poor women globally have been some of the primary victims of the crisis, often because they’re the ones who are in charge of squaring an impossible circle of depressed wages, increased inequality, increase in cost of living, the eradication of Social Security in the welfare state. It’s the women who have to figure out how to feed their children and feed their husbands and so on. And I also think you’re right that 2008 showed the end of certain things that we took to be orthodoxies, sort of clearly evident truths, that growth was always on the rise, that the technocrats fundamentally knew what they were doing and were managing systems that were going to benefit everyone in society and the advanced capitalist countries were going to be kind of beneficiaries of the capitalist engine. So since 2008, especially in countries where something like socialism is an evil word, like the US, there’s been a growing kind of interest, especially among young people, in radical socialist and Marxist feminist alternatives. And the climate crisis is also very much implicated in all of this.

Q. Nevertheless, there is a traditional left that thinks that the identity debate ruined the progressive discourse.

A. I think there’s no question that the radical energies of feminist or anti-racist movements have been successfully co-opted for capitalist ends. It’s really in the interest of corporations to get rid in some ways of the logic of racism and sexism, because what you want are just the best workers, and in a way racism and sexism can be a barrier to get a smooth functioning meritocracy. And what drops always is the class analysis, because to do class analysis to talk about the working class and the oppression of the working class, and the power of the working class, is essentially threatening to capital. But an old left that simply wants to do an analysis on the basis of the wage relation and wants to see things simply in terms of the relationship between the owners of capital and those who sell their labor will never completely understand the stability of capitalism. Why hasn’t the US ever had a very serious working class movement? Racism has a huge amount to do with it. Owners of capital could successfully segregate parts of the working class between white and Black and Latino workers, and create lines of animosity. And similarly, I don’t think you can understand the stability of the stronghold of capital without thinking about unwaged work that women do. So a full analysis of the very thing that old school left people want to give an analysis of cannot be undertaken without so called identity politics.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.