Thin Lizzy’s ‘Live and Dangerous’ remains one of rock’s greatest live albums, even if most of it was rerecorded

The sound quality of the famous concert recording was so bad that much of it had to be reworked in the studio

Tony Visconti’s heart dropped when he started listening to the tapes. He had agreed to produce a live album by a band he loved – Thin Lizzy – even though David Bowie was also impatiently waiting for him to produce an album. Visconti figured the Thin Lizzy gig wouldn’t take long and he could move on to the Bowie album. But then he heard the concert tapes, which were a mess. They were recorded at different speeds, and only some used the Dolby system of recording. When he finally managed to select a few songs for the album, Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott wasn’t convinced. That was when they hatched a plan to produce Live and Dangerous (1978), the greatest live album ever, according to Classic Rock magazine. The concert recording was recently reissued as a remastered, deluxe edition of eight compact discs with plenty of additional material.

Perhaps we should begin this story by saying there was a time when issuing a live album was de rigueur for a rock and roll band. Younger generations of music fans may never have set eyes on one, but more or lesss every pop and rock star has released at least one, from The Who to Beyoncé. The Rolling Stones have about 20 of them. Live concert albums are a genre in themselves that had one fundamental mission – to package up a band’s greatest hits. Sometimes they were released to save careers (Alive!, by Kiss, being an example), and sometimes the aim was to relaunch flagging careers. On many occasions, live albums marked a career retirement or a pivot to a different stage.

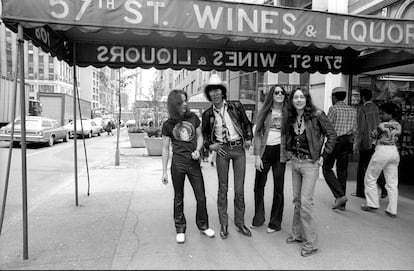

Thin Lizzy already had three good studio albums under their belts by the time they first considered releasing a live one. Inspired by the success of Peter Frampton’s Frampton Comes Alive! (1976), they thought they could do one too. Phil Lynott was the soul of Thin Lizzy, a singer, bassist and songwriter born in England to an Irish mother and a father from British Guiana (now Guyana). His father abandoned the family when Lynott was a few months old, and when he was seven, his mother sent him to live in Dublin with his grandmother. A mixed-race kid, Lynott always felt like the odd one out. Journalist Tito Lesende, the author of a book on the 100 best live rock albums, describes Lynott: “He read Albert Camus, fought constantly, listened to Frank Sinatra and prayed in church with his family.”

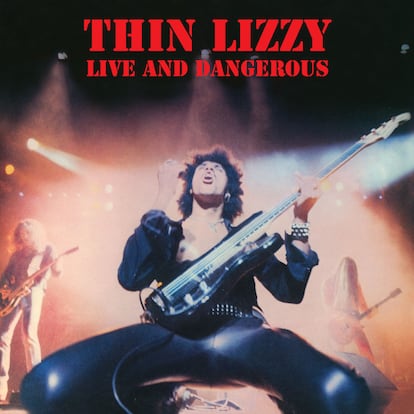

His songs were about gangsters, Irish heroes and tough guys bruised by heartbreak. People who acted tough to hide deep vulnerabilities. In Cowboy Song: The Authorized Biography of Thin Lizzy’s Philip Lynott (2017), Graeme Thomson writes: “Lynott embodied the paradigm of the rock and roll bandleader. He controlled, manipulated and electrified crowds, and became indelibly associated with the cover of Live and Dangerous – a Dionysian portrait in leather pants, clenched fist, spiked wristband and pirate earring.”

To put Live and Dangerous together, Visconti was given concert tapes from a 1976 London performance at the legendary Hammersmith Odeon, and two 1977 shows at the Tower Theater in Philadelphia. Once he had finished the “nightmarish” job of cobbling together the poor recordings, Phil Lynott showed up to listen. In his memoir, Bowie, Bolan and the Brooklyn Boy, Visconti writes: “We corrected a couple of bass notes in the studio and then Phil said, ‘It sounds great, but how about if I rerecord all the bass lines for the record?’” Lynott then decided he wanted to rerecord all the vocals and some guitar parts. The producer later revealed that 50-75% of Live and Dangerous had been rerecorded. Thin Lizzy guitarists Brian Robertson and Scott Gorham say that Visconti is exaggerating, but don’t deny that the album needed major touchups. It’s a common practice for live albums, but Live and Dangerous stands out because it’s such a legendary album and so much reworking was needed.

Michael Hann, a contributor to The Guardian and Rolling Stone, and author of a history of British heavy metal (Denim and Leather, 2022), writes in The Quietus: “For some, Live And Dangerous is discredited because of the suspicion of it being largely a studio album. But, really, does it fucking matter? Even if lacks veracity, it has verisimilitude. It sounds like you are at a phenomenally exciting rock & roll show: it roars out of the speakers at you, in a way that makes you feel as though you might have been standing in the stalls at Hammersmith Odeon.” Tito Lesende agrees. “You can clearly hear the drums and the audience from the original recordings, but can’t be too sure about the rest. It may have been reworked with studio overdubs. It was obviously doctored, but what difference does that make? Others would have produced a meme record, but this one is so well done that it represents a Thin Lizzy concert better than the original recordings.”

Visconti achieved a live sound by setting up stage equipment in the studio. He even attached a radio transmitter to Lynott’s bass guitar so he could move around the studio as he did in concerts. Lynott told the producer that he wanted to feel the booming sound under his feet, just like at a gig. Then, the audience cheers and sounds from the live recordings were enhanced to provide the live performance feel. Spanish rock historian Mariano Muniesa notes: “The album’s main strength is that it faithfully presents the energy of a Thin Lizzy concert. It’s a sincere album that captured the essence of a live performance by the legendary band.”

The songs on the album are superb: rough tunes like Jailbreak and Massacre; a ballad – Still In Love With You; the wonderful Cowboy Song; classic hit The Boys Are Back In Town; and the bluesy Don’t Believe A Word. Robertson and Gorham traded guitar solos, a much-imitated style that influenced Iron Maiden and later generations of metal bands. Lynott’s deep, passionate vocals often sound like narration, and his funk basslines underpin the songs with their special rhythms. These are the things that set Thin Lizzy apart from many of the bands of their generation.

People often wonder why Thin Lizzy didn’t take off more. Musiesa says: “They came up at the same time as the great hard rock monsters of the early 1970s – Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin – and the new wave of British heavy metal of the late 1970s like Iron Maiden and Saxon… They peaked in popularity at a time – the mid-1970s – when the genre was going through a period of transition and wasn’t all that popular.”

Soon after Live and Dangerous was released in 1978, friction between Lynott and Robertson pushed the guitarist out of the band. Thin Lizzy eventually split up in 1983. Three years later, Lynott was hospitalized, on December 25, 1985, after a heroin and alcohol binge. He died on January 4, 1986, at the age of 36.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.