Wendy Carlos: The brilliant but lonely life of an electronic music pioneer

The musician helped create the Moog synthesizer and composed groundbreaking albums and film scores, but lived in seclusion for almost 10 years to hide her gender reassignment

It’s no exaggeration to say that Wendy Carlos is the most important living person in the history of electronic music. The creator of some of the most hallucinatory and terrifying soundtracks in the history of cinema, Carlos was born in 1939 to a working-class family in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, a historic East Coast city less than four hours’ drive from New York City. When she was only six, her musically oriented parents were so enthused about her piano playing that they drew a keyboard on paper so she could practice between lessons, as they could not afford to buy her an instrument.

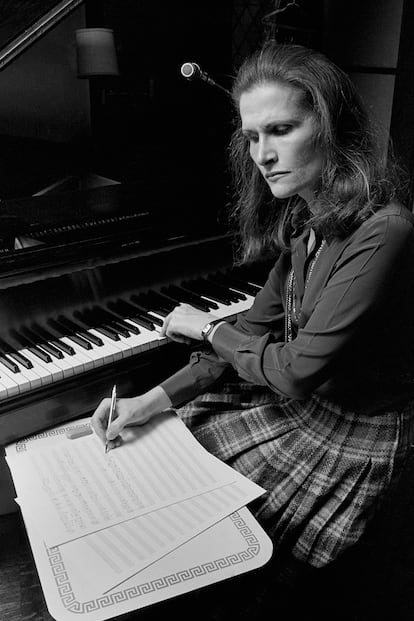

She was born Walter Carlos, but says she always felt like a girl. She liked long hair and girl’s clothing, and didn’t understand why her parents treated her like a boy. Over the years, she began to realize how difficult it was for society to accept people who were different. The challenge that endures to this day was even more pronounced in conservative New England during the 1940s.

But Wendy was a unique child in many ways, and demonstrated an exceptional talent for music and gadgetry from an early age. She wrote her first composition, “A Trio for Clarinet, Accordion, and Piano,” at 10, and then started sawing wood and soldering wires to build a hi-fi system for her parents from scratch. In 1953, when few people had even heard of a computer, the 14-year-old Carlos won a scholarship to build one.

After a childhood and adolescence marked by gender dysphoria and merciless taunting by classmates, the future musician entered Brown University (Rhode Island) where she studied music and physics. In a 1985 interview with People magazine, Carlos said she tried to conform in college and even went on a few dates, but they didn’t go well.

Carlos steeped herself in classical music during those turbulent college years, and discovered that she loved the musical, mechanical and expressive aspects of electronic music. After graduating from Brown, she continued to study and compose music, gradually incorporating electronic elements. In 1965, Carlos graduated from Columbia University (New York) with a master’s degree in music composition, where she rubbed shoulders with Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening, two pioneers of electronic music who worked at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York City.

During her time at Columbia, Carlos met Robert Moog and developed a career-defining partnership with the man whose name is on the first commercial modular synthesizer. Carlos provided musical advice and technical help to Moog as he developed the instrument that would revolutionize music in the 1960s.

The Moog synthesizer quickly became part of the pop revolution and spawned the new genres of progressive and electronic music. German electronica bands like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk used the Moog extensively, and the last few Beatles albums also featured synthesizers. Carlos came up with the idea of adding filter banks, pitch adjustment sliders and a pressure-sensitive keyboard to the Moog. “In my entire lifetime, I’d only seen a very few people who took so naturally to an instrument as she did to the synthesizer,” Moog told People magazine. “It was just a God-given gift.”

In 1966, Carlos got her own Moog and began adapting classical music to the synthesizer and creating her own compositions. To earn some money, she used her Moog to create sound effects and jingles for television commercials. Around that time, she met and shared a Manhattan apartment with Rachel Elkind, a singer and producer who worked for Columbia Records. Elkind’s introductions helped her get a recording contract in 1968 for Switched-On Bach, an album of Johann Sebastian Bach pieces performed on the Moog.

Columbia Records had low expectations for the album and only gave Carlos a $2,500 advance, opting instead to compensate her with a higher percentage of future royalties. Released in October 1968, Switched-On Bach became an unexpected commercial and critical success, becoming only the second classical album and the first electronic album to go platinum in the United States. It also helped draw public attention to the synthesizer as a genuine musical instrument.

At the same time, Carlos was getting counseling from sexologist and transgender rights advocate, Dr. Harry Benjamin. She began receiving hormone treatments, a prerequisite for an eventual sex change operation. It was something Carlos had been considering for a long time, and Dr. Benjamin’s counseling reaffirmed her decision. The hormone treatments began showing visible effects at a time when her first album was attracting enormous media attention. Overnight, Carlos became a world-famous musician and composer – the electronic music radical – and offers to perform live began to stream in.

In 1969, Carlos was invited to perform her electronic Bach pieces with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra before a live audience. But what was supposed to be an induction into the American musical firmament turned into a nightmare for Carlos. Crying in her hotel room, she told her producer, Rachel Elkind, that she was terrified of going onstage. The estrogen treatments had transformed her appearance – she now looked like a woman – and she was panicked about the audience’s reaction.

From today’s vantage point, Carlos made a sad decision. Before she took the stage, she donned a man’s wig, pasted on fake sideburns, and had a make-up artist add beard stubble to her face. The performance was a smashing success, but Carlos decided to never perform live again.

Carlos developed a phobia about being seen in public and became a recluse in her home studio. Famous musicians – Stevie Wonder, George Harrison and Keith Emerson – showed up wanting to meet her, but Carlos couldn’t face them. Her visitors were told that Carlos was away. “I would listen to them from upstairs,” Carlos told People. “I accepted the sentence, but it was bizarre to have life opening up on the one hand and to be locked away on the other.” When forced to go out in public for television appearances and interviews, she went disguised as a man.

She used her disguise to appear on the BBC and The Dick Cavett Show. When Stanley Kubrick asked Carlos to write the score for A Clockwork Orange, she dressed in men’s clothing for their meetings. “I could tell he felt something was strange,” she says. “But he didn’t know what.”

The wild success of Switched-On Bach enabled Carlos to meet Kubrick and turn several Purcell, Beethoven and Rossini pieces into a chilling synth score for A Clockwork Orange, and also gave her the freedom to venture into unexplored musical terrain. In her 1972 double album, Sonic Seasonings, Carlos dedicated an entire side to each of the four seasons. She didn’t want to produce music that required focused attention, but instead sought to recreate moods.

For her venture into mood music, Carlos combined outdoor recordings of animals and nature with sounds created on her synthesizer to produce a soundscape just as haunting as her earlier work. Sonic Seasonings represents another Carlos-created leap forward for electronic music and is the first ambient music album, even though Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978) is thought by many to be the first of the genre. The release of this new album coincided with another key event in the musician’s life. In May 1972, Carlos finally completed her sex change and officially became Wendy Carlos.

Outwardly, nothing changed, and Carlos continued to live in seclusion in her New York apartment. As Arthur Bell said in his 1979 Playboy interview with Carlos, she had become a latter-day Phantom of the Opera. That interview was her official coming out, though Carlos later called it “a betrayal” because only a few paragraphs of the 15-page article talked about her music. Still, it’s a unique insight into the suffering Carlos endured during a lifetime of gender dysphoria. Up until that point, she had released eight albums as Walter Carlos as she lived in self-imposed secrecy.

During that long period of seclusion, Carlos had almost no contact with other musicians or the electronic music industry that she had pioneered. She invented all kinds of excuses to hide and maintain the fiction of Walter Carlos, because transsexuality remained the last great sexual taboo in American society.

Perhaps to relieve the stress of eluding the spotlight, Carlos took up the esoteric hobby of photographing solar eclipses, which took her to far-flung places like Siberia, Bali and Australia. According to her friend and collaborator, Annemarie Franklin, Carlos acquired a well-deserved reputation as a leading eclipse photographer.

After being voluntarily outed in Playboy, Carlos continued her brilliant composing career. She again collaborated with Kubrick for The Shining. Although she created a complete soundtrack for the film, Kubrick ended up using only two pieces. The discarded compositions remained unpublished for decades until they were released in 2005 in an appropriately-titled album – Rediscovering Lost Scores. Her commercial success enabled Carlos to move into a larger apartment in which she built a Faraday cage to shield her equipment from electromagnetic fields that caused white noise and interference.

In 1980, Carlos was commissioned to compose the soundtrack for Tron (1982), a science-fiction film that became some of her best-known work. Carlos used new digital and analog synthesizers for the soundtrack and incorporated recordings by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the University of California choir and the Royal Albert Hall’s famous pipe organ. The end result was an album that is much richer and less overtly electronic than some of her previous work, which may be why it has stood the test of time so well – perhaps better than the film itself.

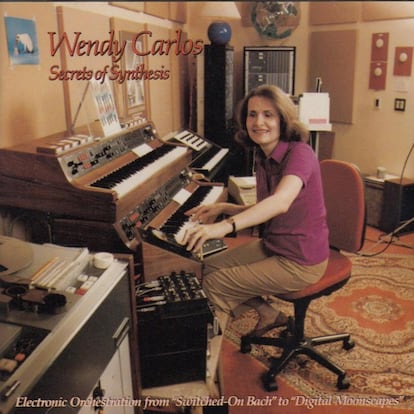

Other studio albums followed Tron, including Digital Moonscapes (1984), the first album to exclusively use digital synthesizers, a complex undertaking given the state of technology at the time. Carlos invented a “digitally synthesized orchestra” with more than 500 “voices” that she created one by one over a three-year period to replicate symphonic instruments. “Wendy has built up lyrical sounds nobody ever heard coming out of a digital synthesizer before,” Moog told People. “Nobody is in her league.”

The People article coinciding with the release of Digital Moonscapes concludes that Wendy seems to have finally found the peace that eluded her for so many years, and that she was even planning to resume performing in public. “It will be fun,” she said, “to get out into the open again.”

Her return to public life never happened, although Carlos continued to work. Now 83, she supposedly remains active in music, but is still an elusive figure who fiercely protects her work.

Carlos’ recordings are hard to find on streaming music services because she owns most of her catalog and has not authorized its release on those platforms. She also spends considerable time and money combatting those who post her music on the internet without her consent.

The last time we heard from Wendy Carlos was a brief note posted on her website (a nostalgic trip to the early days of the internet) in August 2020. Carlos denounces the unauthorized book by musicologist Amanda Sewell, Wendy Carlos: A Biography (Oxford University Press), saying that she was never interviewed for the book, which was based exclusively on write-ups of other interviews done for magazine articles.

Wendy Carlos will be remembered as an exceptional woman who was never able to fully enjoy her well-deserved success. Her self-imposed seclusion is a cautionary tale for us today, something that she admitted in the 1979 People interview. “The public turned out to be amazingly tolerant or, if you wish, indifferent,” she said. “There had never been any need of this charade to have taken place. It had proven a monstrous waste of years of my life.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.