Ahmad Jamal, pianist: ‘You turn on the TV and never see Billie Holiday… that’s when you know the world isn’t doing well’

The legendary musician – who, at the age of 92, has released two of his unedited tracks from the 1960s – spoke to EL PAÍS about a career that has spanned eight decades

Ahmad Jamal, at the age of 92, has the history of piano at his fingertips. As one of the last survivors of the golden age, he’s a musical legend.

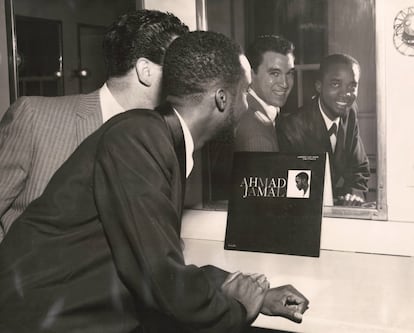

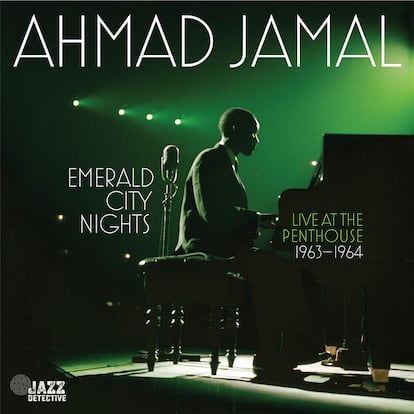

He recently released two albums, filled with live recordings that took place between 1963 and 1966 at the Penthouse Club in Seattle, Washington.

“I wasn’t so thrilled [about the music] from 59 years ago. But they convinced me to release the tapes,” Jamal told EL PAÍS via telephone.

Jamal –who lives in the Berkshires, Massachussets– accepted the request for an interview in November of 2022, with a few conditions. This reporter was forbidden to mention the names of two particular dead jazz critics, or ask Jamal any questions based on what is available on Wikipedia.

In 1948, he moved from Pittsburgh to Chicago – his “second home”. “I worked for 80 cents an hour installing kitchens. I played music in my spare time. Israel Crosby (a double-bassist) was the man who first hired me,” he recalls.

Crosby – who died in 1962 – was one of the members of a legendary trio, which included Jamal on piano and Vernell Fournier on drums. The group made its recording debut with one of the most famous albums in jazz history: At the Pershing: But Not for Me (1958).

“That record got us the spotlight,” Jamal says proudly. “Many people have tried to imitate that sound, but they’ve failed.”

The Ahmad Jamal trio – which competed with the likes of Chuck Berry and Ritchie Valens for popularity – distinguished itself by using a minimalist, spacious touch. Their music overflowed with imaginative arrangements, giving infinite life to the songs, while the rapport between the musicians was solid.

Many years later, in his memoir, Miles Davis praised Jamal’s influence on jazz music:

“[In the mid-fifties] I admired his lyricism on the piano, his style of playing, the spacing he used…. I’ve always thought that he didn’t get the recognition he deserved.”

The Penthouse Club in Seattle, Washington was one of Jamal’s favorite places to play.

“There was extraordinary respect for music. If you made a ruckus, they kicked you out of the joint.”

Charlie Puzzo – the club’s owner – was in the habit of recording artists who were doing their residency at the Penthouse. He held a weekly radio broadcast on Thursday nights.

“There were an enormous number of tapes – about 100 hours in total – from a wide variety of artists,” music producer Zev Feldman explains in a telephone conversation. “The [Puzzo] family made me co-custodian of that material.”

Feldman recently contacted the pianist, although he didn’t have much hope that Jamal would agree to authorize the sale of previously unreleased recordings. “He has a reputation for saying ‘no’ to these things.”

But Jamal surprised him. With two volumes of newly-discovered recordings having been released in 2022, Feldman is already promising a third volume of Jamal’s live performances, which took place at the Penthouse between 1966 and 1968.

In his interview with EL PAÍS, Jamal clarifies that he doesn’t like to be referred to as a “jazz” musician – he considers this label to have racist echoes. What he really creates is, simply, “American classical music.”

“The only genuine cultural products of this country are Native American art and African American classical music. I don’t distinguish Bach or Beethoven from Duke Ellington,” he affirms. “Without Louis Armstrong, Billy Strayhorn, Sidney Bechet or Don Byas, the Beatles wouldn’ have existed, nor everything that came after them.”

“Music no longer really exists. You turn on the TV and you never see Billie Holiday… that’s when you know the world isn’t doing well.”

When asked if his many albums have made him rich and famous, Jamal snorts. “Being rich isn’t about what you have in your pocket, my friend. It’s about what you have in your head. Peace of mind. That’s why so many millionaires are poor.”

To make his case, the pianist recalls a 2018 performance he gave in Ukraine. “It was one of the biggest concerts of my life. Everything was normal then. Now, chaos reigns – there are six million refugees. There’s no peace of mind for those people. I’m sure they would give all the money in the world to get it back.”

During the conversation, the musical legend often shows more interest in talking not so much about his craft, but rather about current events, from climate change to the protests in Iran. Or the strangeness of contemporary life, such as computer scams –he was just the victim of one – or “the thousands of passwords that we have to enter just to do anything.”

Jamal is now retired. He has “two Steinways at home,” but rarely touches them. He recorded his last album in 2019, for a French label, where he is adored.

“A few days before the (COVID) lockdown, I played in Washington.” It was the end of a career that began professionally “at 10 years old,” just when World War II was in its early stages. He went on to play “with a group of musicians in their fifties” who “couldn’t believe” that the young man already knew the repertoire inside-out.

“Repertoire is the most important thing, whatever musical style you play.”

The rescued tapes from the early stages of Jamal’s career hit the stores on Black Friday. The recordings – all of them of optimal quality – allow listeners to hear the pianist perform with different bandmates. The songs also reveal Jamal’s experimentation with different tunes, before his style matured in the 1970s.

Little did Jamal know that, decades after the prime of his career, his musical production would be widely consulted by the hip-hop movement. However, when asked if he’s interested in rap – a genre that has taken so much inspiration from him – the pianist hesitates.

“Everything is fine by me… so long as I get paid. But that’s very difficult. I actually had a fallout with Jay-Z because of that and had to get my lawyers involved.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.