The medieval monks who forged a nobleman’s will to appropriate a valuable church

Spanish scientists have discovered that the religious community of San Pedro de Cardeña doctored the document out of greed - but forgot to eliminate the original

The monks of the San Pedro de Cardeña monastery, in Spain’s Burgos province, had long had their eye on the Santa María de Cuevas de Provanco church in Segovia. But the substantial inheritance that the Count of Castile, Asur Fernández, and his wife Guntroda, bequeathed them made no mention of this Romanesque church surrounded by beautiful vineyards.

Such was the ambition of the monastery to own the church that two hundred years after the death of the Count, they forged the parchment on which his will was written. Their only mistake was an omission to remove all the copies of the authentic will. Now, the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the University of Burgos have been able to demonstrate that the fraudulent document, considered until now to be the oldest of those kept in the Historical Nobility Archive in Toledo, is in fact a forgery from the 12th century, and not from the year 943, as it claims.

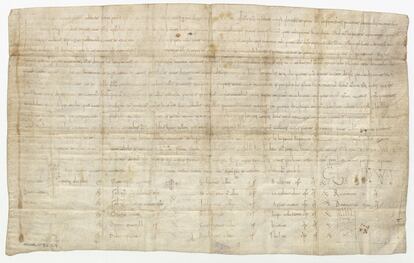

The document faked by the monks – officially known as OSUNA, CP.37, D.9 – is a parchment on which round Visigothic script records a donation from the Count of Castile to the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. Until now, the document was thought to be somewhat unique as hardly any original documents from the 10th century survive in Castilian Spanish. However, research has shown that it was actually drawn up two centuries later.

The research, to be made public shortly in the Medieval Studies Annual Report, has revealed which procedures were employed to doctor the will, as well as the motives that led the monks to do so. The forgers based their work on an authentic document stipulating a donation from the Count, inserting elements that were not in the original, in order to use it as evidence in potential lawsuits, two of which were subsequently filed and won by the monks.

The analysis of the document, carried out by Sonia Serna from the University of Burgos, has exposed anomalies both in its preparation and its writing. Serna explains that the scribe was accustomed to working with the 12th century Carolinian script, and made an effort to imitate the round Visigothic script typical of 10th century Castile. But anachronistic features crept into his work, such as the use of the Carolinian system of abbreviations and the adoption of anomalous solutions to abbreviate some words, elements that would not have existed in the 10th century. All the same, the forgery proved effective enough to win two court cases.

The forged document included a clause that ceded the church to the Burgos monastery

The original document used by the monk as a model for his forgery was lost. However, a copy survived in the collection of charters, known as Becerro Gótico de Cardeña and kept in the Zabálburu Library in Madrid. By comparing both texts, Julio Escalona from the CSIC History Institute verified that the monk copied the wording and appearance of the authentic will, but inserted a clause assigning the church of Santa María de Cuevas de Provanco to the monastery of San Pedro.

In 1175, the church of Santa María de las Cuevas was the subject of litigation between the monastery of San Pedro and the councils of Peñafiel and Castrillo de Duero. The Burgos monastery finally won by presenting the false parchment document and getting two monks to testify its authenticity. According to the experts, that document was the will filed in the Toledo archive, whose anomalous paleographic features are consistent with an elaboration in the second half of the 12th century, taking the original as a model.

“Its value does not lie in the anecdotal fact of its being or not being the oldest document in the archive [as was believed until now], but in showing how technical skills and moral and religious authority combined in this case to build a credible truth, capable of triumphing in a judicial scenario,” states the CSIC and University of Burgos study. “Ultimately, it reminds us that to fully understand any historical period, it is essential to understand how each period rewrites and manipulates its past.”

The monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, where the forgery was made, was completely plundered by the Napoleonic troops during the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808. The monks fled in terror and had to abandon all the treasures they had been guarding for centuries. One of the desecrated tombs was that of El Cid – or Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, with Napoleon’s soldiers selling off his weapons and remains throughout Europe. They even made engravings reflecting the plundering of the tomb of the legendary warrior. Today, a plaque states that although the remains of the Castilian hero are no longer here, his horse is buried in the monastery’s garden, though this may be no more than a myth.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.