The Hand of Irulegi delivers more questions than answers on Basque origins

Experts admit the 2021 find is being used for political gain and that the ancient artifact has exacerbated an age-old controversy about the genesis of the language

The 2021 discovery of the Hand of Irulegi 10 km from Pamplona has rekindled a debate on the origins of the Basque people and their language. A bronze artifact dating back 2,100 years that supposedly includes the first words ever to be written in Basque has thrown up questions such as whether or not the Basque culture derives from populations of the ancient Aquitaine – north of the Pyrenees, in modern-day France – or from those settled in what is now the Spanish region of Navarre.

Experts also disagree on whether the Hand of Irulegi is actually inscribed with the first words written in Basque or if the words are in fact written in Celtiberian language or even in Latin but engraved in a combination of letters and symbols of an indigenous language. The problem is further complicated by the political and cultural implications, since linguists place the original use of Basque in the Spanish regions of Navarre, La Rioja and Aragón, rather than in the present-day Basque Country, where Basque allegedly was not spoken, except in the area of ancient Oyaso, which is now the city of Irun, on the border with France.

It is a complex issue which Juanjo Sayas, a professor of ancient history at the long-distance-learning university UNED, believes contributes to the “Basque controversy.” Meanwhile, Javier Andreu, a professor of ancient history and director of the Archaeology Diploma course at Navarre University, criticizes the “political use” of the finding, comparing it to an ancient bronze Roman-era sculpture known as Togado de Pompelo which was returned to Spain last June. “The best bronze of the Iberian Peninsula and one of the best in the West arrived [from the United States] at the Museum of Navarre, and the leader of the regional government was not even there to receive it,” he points out. “Now, a hand measuring 14 by 12 centimeters shows up and there has been no end of ceremony, with the Navarrese premier taking part.”

The authenticity of the finding is not in question. The Aranzadi Science Society has documented the unearthing process in detail, says Alicia María Canto, a professor and epigrapher at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who was the first to point out “oddities and impossibilities in the revolutionary graffiti” of Iruña-Veleia in 2006, a widely reported case of Basque epigraphic forgery that ended in court.

With the unearthing of the Hand of Irulegi last year, old arguments have surfaced. Canto believes that the discovery just 10 kilometers from the old Roman city of Pompaelo (modern-day Pamplona) will make it hard to reject the idea that in the distant past – except in the coastal area of Irun – the present-day Basque Country was inhabited by Indo-Europeans rather than the pre-Roman Vascones, while also making it hard for anyone in Navarre to deny that Navarre was the true cradle of the Vascones. Josetxo Beriain, a professor of sociology and social work at the Public University of Navarre, believes that the relevance of the hand is that it generates “a new beginning, since all communities try to establish a departure point from which their identity is scattered.”

Beriain believes that the finding “can represent a certain conquest of the past as a way to conquer the future, given that we were already there when the Romans arrived.” What still cannot be determined is whether the Vascon culture accepted Roman culture or imposed its own. According to Beriain, it is likely that today’s nationalist sectors use the find to claim that the Basque culture was not subjugated, although “that is an ideological construction rather than a historical construction.”

Experts stress that the four lines of the inscription are important because they may be an indication that Pamplona was the cradle of the Basque people

Did the Basque people therefore move from Navarre to the Basque Country in the ancient past? Sayas believes that the scarcity of information on the more northern reaches of these communities has to be taken into account. But everything points to the fact that Rome used geographical criteria to divide the ethnic groups. This meant they took advantage of “the Pyrenean massif to establish the division between Gaul and Hispania,” although before the Romans there was a cultural homogeneity between the peoples on both sides of the Pyrenees. The division was made on a map and did not always take into account ethnic groups, settlements or cultures; only administrative interests. In this sense, it cannot be ruled out that different ethnic and linguistic groups converged on Basque territory. In fact, in different texts, there is mention of Celtiberians who in the 2nd century BC proclaimed themselves to be descendants of the Celtiberian world, but there is no one who proclaimed themselves to be a Vascon from the 1st century BC until the end of Romanization, according to Sayas. “There are, however, testimonies of those who considered themselves Pompelonians, Carenses and Andelonians,” he says.

Meanwhile, Andreu flags up the fact that Viana, a site in Navarre where numerous texts have been discovered in Celtiberian but none in Basque, is barely 90 kilometers from Irulegi. The coins found on Basque territory from that period are also inscribed in Celtiberian. This is further proof that “in Navarre, in ancient times, Basque, Iberian and Celtiberian were spoken. Most likely,” Andreu adds, “this area was a melting pot of cultures and languages long before the Romans arrived.”

“Most likely, this area was a melting pot of cultures and languages long before the Romans arrived,” says professor Javier Andreu

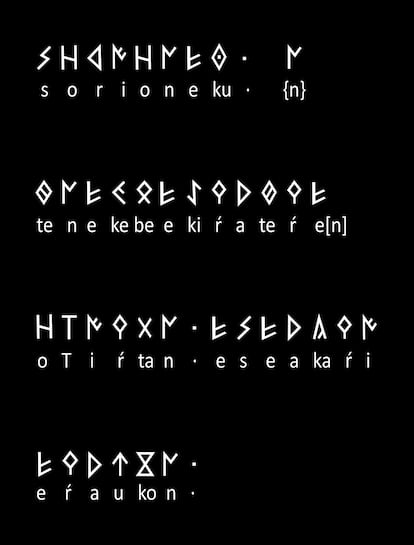

As for the language in which the Hand of Irulegi is written, both Joaquín Gorrochategi, a professor of Indo-European linguistics and, Javier Velaza, professor of Latin philology, have concluded that the text is written in archaic Basque. In fact, in their opinion, the first word to be deciphered is sorioneko, linking to the current term zorioneko, which can be translated as good fortune, and which appears to have been written in an adaptation of the Iberian characters, but with some Basque characters to reflect sounds typical of the language.

There are other interpretations, such as the one given by the archaeologist Guillermo López, from the Archaeological Studio consultancy, who maintains that these symbols are similar to those found on hundreds of Celtiberian pots unearthed in Navarre, La Rioja and Aragón. Moreover, he suggests that this inscription contains Latinized features, a consequence of the Romanization of the area, and that the artefact was used as a token of friendship rather than being a decorative object. That is to say, he believes there were two hands, the right one, found in Irulegi, and another left one still to be unearthed in the town in which a supposed treaty was signed.

Andreu rejects this hypothesis but does not rule out that sorioneku could be a word derived from Latin because “in ancient languages these concomitances exist.” He also finds similarities between the Hand of Irulegi and the so-called Stela of La Vispesa, a symbol of protection typical of the Iberian culture. Alicia Canto also suggests there may be a link to the Stela of La Vispesa, though she does say the hand could be simply and literally be “a severed limb, a classic amputation of Iberians and Lusitanians against enemies, which could have been exhibited as a trophy at the entrance of houses or shrines.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.