Flavia Sabora: Lost Roman town is rediscovered under a crop field in Spain

University of Cádiz researchers used georadar to locate the ancient settlement, which has documented traces of streets, thermal baths and other buildings

Caius Cornelius Severus and Marcus Septimius Severus traversed more than 2,300 kilometers (1,430 miles) from what is now Málaga, Spain, to Rome to seek an audience with Emperor Vespasian. They arrived in August of the year AD 77 and three days later were granted permission to make their two requests. Vespasian, the most powerful man in the Roman Empire, accepted their petition to move the location of their town, Sabora, to more fertile land nearby but refused their suggestion that they collect their own taxes. In exchange, the new settlement was to be renamed Flavia Sabora, in honor of Vespasian’s dynastic house. Today, we are aware of the ins and outs of that meeting because it was engraved for posterity on a bronze that endured until the 18th century. The new city the two men planned did not fare so well and became lost in the mists of time. That is, until now, when it was rediscovered under a grain field in Cañete la Real, a town in Málaga province that has served to reveal a hidden part of the region’s Roman history.

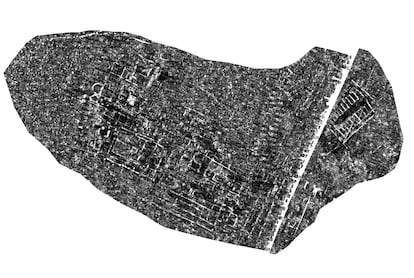

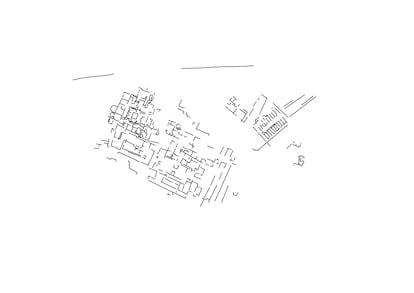

Scientists from the Geodetection Unit at the University of Cádiz (UCA) have identified the layout of what appear to be streets, public spaces and even thermal baths or a nymphaeum in El Carrascal, a rural crop-growing area on the outskirts of Cañete, the name of which is thought to derive from the Spanish word for spring or spout. Through the use of drones, georadar and data-processing using computer software - a technique known as non-invasive archaeology - the researchers have managed to scan the subsoil across an area of more than two hectares, under which the entire layout of a possible Roman town appears. “It is too large to be a village and too small to fit the profile of a large classical Roman city. It fits more with the concept of a small town, a civic, religious and administrative center that served a larger rural area,” says Lázaro Lagóstena, a professor of ancient history and head of the UCA Geodetection Unit who for decades has specialized in the study of landscapes and ancient rural areas.

On a nearby hillside, Lagóstena’s team has been able to identify the remains of streets organized in the classic Roman cardo-decuman arrangement (two roads running north to south and east to west), and areas with the possible remains of pavements - ”these are probably mosaics,” Lagóstena points out - an apse typical of a thermal space and even the remains of four niches that could fit the typology of a nymphaeum, a place of worship linked to water. In Lagóstena’s view, all these lines traced by georadar fit directly with the layout of “an administrative center of the Flavian dynasty,” which ruled the Roman Empire from AD 69 to AD 96. Therein lies one of the greatest values of the discovery: “It is a city that was built in a single phase, so it is ideal for studying the urban planning of that period,” the expert notes.

The UCA team - which has already garnered fame for its discoveries in Hasta Regia (Jerez) and the Punic port of Doña Blanca (El Puerto de Santa María) - alighted on Flavia Sabora two years ago through a chance discovery made by Antonio Aranda, a researcher and a resident of Cañete la Real. “While looking at some satellite images, he noticed that the outlines of some buildings were visible,” says Andrés Morón, Cañete’s deputy mayor and councilor for Historical Heritage. The discovery served to shed light on one of the great historical debates of the area, whereby several different hypotheses had been put forward as to the location of the lost Roman site. “El Carrascal is a completely different location than everyone thought,” says Morón.

Although Flavia Sabora’s exact location was an enigma, the settlement’s story was not. The Roman author Pliny the Elder, who wrote the Naturalis Historia, described it in the 1st century as an oppidum, or a settlement on a hill. “That is to say, a population of pre-Roman origin, subject to the control of and payment of taxes to Rome,” the UCA researchers wrote in their report of the finding for the Spanish Ministry of Culture. The first population center was established on the hill of Sabora, a defensive position located next to the current town of 1,600 inhabitants. But as Morón notes: “It is very cold there and there is a shortage of water.” With the security provided by the Roman conquest in terms of protection and prosperity, the second variable prevailed, as demonstrated by the request of the two municipal representatives to Emperor Vespasian.

Vespasian’s favorable decision on moving the settlement to more fertile land was preserved in bronze - a classic material in Roman legal epigraphy - to be exhibited to all in the new town. And there it would have remained, despite the decay of a municipality that did not prosper for very long, pushed into extinction by the crumbling of the urban centers in the Roman province of Baetica from the middle of the 2nd century onward. “Flavia Sabora’s life spanned just two or three generations. It was caught by the degradation of the cities. The nucleus moved over time back to the nearby hill, during the Islamic period, and then to the current location of Cañete”, says Lagóstena.

Engulfed by neglect, Flavia Sabora would have disappeared from history entirely were it not for a local farmer, sometime between 1517 and 1551, coming across the bronze plaque that told the story of its foundation. The piece ended up in the court of Spanish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and remained there until it disappeared from the records in the 18th century, probably devoured in the fire that gutted the Alcázar of Madrid in 1734. Fortunately, by the time the fire occurred, the text was well-known and had been transcribed. The discovery by the UCA team has finally located the exact spot from which the bronze originated and opened up new possibilities for research. “The next phase would be to analyze the site space by space, looking for parallels with other cities of the same period,” says Lagóstena.

Whether the team will be able to carry out that task or not is conditional on Flavia Sabora’s selection as a funded research project by the Andalusian regional government, but in Cañete la Real residents are determined not to lose their Roman heritage again. Morón says he is already taking steps to persuade the local authorities to initiate proceedings to protect the site as a designated asset of cultural interest, thus shielding the find from the attention of possible looters. At the same time, Morón underlines the local council’s intention of attempting to “buy the land from the current owners for a fair price,” before the expected protection status from the regional administration makes it less valuable for them. Then, perhaps, excavation and restoration could be carried out to make Flavia Sabora visitable for tourists. In the meantime what is certain is that the Roman settlement won’t disappear from history again.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.