The real story of Spain’s El Cid: medieval hero or shrewd mercenary?

Many of the episodes that people know from books and movies never really happened, says scholar David Porrinas. But Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar’s life and exploits were still extraordinary

The real El Cid, the man named Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, did not own two swords that he called Colada and Tizona, nor did he have a horse named Babieca, and he never forced King Alfonso VI to swear that he had nothing to do with the death of the monarch’s brother.

Also, his daughters’ names were not really Elvira and Sol, but María and Cristina, and he had a son named Diego. Nor is it true that his daughters were assaulted by the counts of Carrión, or that he himself won a battle after death.

As a matter of fact, it could well be that nobody called El Cid by that name during his lifetime, although he did go by the name of “Campeador” (from the Latin campidoctus, or lord of the battlefield), which he attached to his signature.

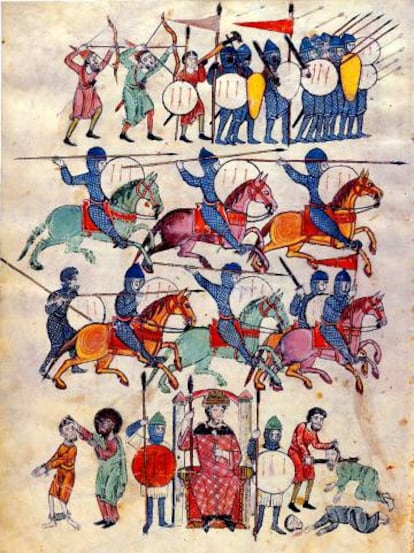

He headed a hybrid army made up of members of his own armed retinue as well as Muslim troops

But this does not mean that the real-life individual and his exploits were not extraordinary in their own right.

Now, a renowned medieval history scholar named David Porrinas, who teaches at Extremadura University, has published an enlightening new essay on the real Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, who was born around 1040 and died in 1099.

El Cid, historia y mito de un señor de la guerra (or, El Cid, history and myth of a warlord), focuses on Díaz’s battlefield activities and depicts him as a man of action. He was an adventurous, opportunistic and pragmatic warrior who was adept at navigating the often hazy frontier separating Christian and Islamic Spain. He headed a hybrid army made up of members of his own armed retinue as well as Muslim troops. He was a mercenary in search of booty, and a strong leader to follow in a mixed-up world where Christian and Muslim kingdoms fought against each other and among themselves, switching alliances regardless of religion.

He was a fearsome fighter who could prove brutal – he had civilians tortured and ordered the Muslim judge of Valencia to be burned alive – and he earned a reputation for being invincible in battle. Both the character and the backdrop are powerfully captured by the writer Arturo Pérez-Reverte in his latest novel, Sidi, although the latter also includes a few legendary elements from the popular accounts about El Cid.

“It is very complicated to extract the real, historical Cid from the legend that was created around him,” explains Porrinas, underscoring that some enduring clichés have been around for so many centuries that it is difficult to banish them, as Díaz himself was banished twice by the king.

But that is not for lack of good historical sources, he notes. “He is probably the character who attracted the greatest news coverage of his time, even more than the emperor himself, Alfonso VI. It is an absolutely exceptional thing to have this much information about someone from the 11th century who was neither a member of royalty or a high-ranking church official,” says Porrinas.

One of these historical documents is the Historia Roderici, which was written during El Cid’s lifetime or shortly thereafter. There are also accounts by Muslim chroniclers who wrote about the conquest of Valencia, El Cid’s greatest military feat. Some of these historians even experienced the event first-hand.

Porrinas explains that even the document recording the marriage between Díaz and Jimena has survived, and that it shows Díaz’s own signature “Ego ruderico” (I, Rodrigo). The halting writing suggests that El Cid was much better with a sword than with a quill.

He was a fearsome fighter who could prove brutal: he had civilians tortured

Despite these sources, it is the Cantar de mio Cid, an epic poem that was put down in writing between the late 12th and early 13th centuries based on minstrel accounts, which has dominated the public’s view of events. “It established a literary imagery that’s very different from the historical one, but which was destined for much greater success,” notes Porrinas.

The confusion was compounded by the fact that in the early 20th century Ramón Menéndez Pidal, a noted historian and scholar of Spanish folklore, decided that Cantar de mio Cid and other romances about Díaz de Vivar should be considered valid historical sources to learn about the real man.

And then there was the Franco regime’s praise of the national hero, not to mention the 1961 movie starring Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren. The imagery contained in Cantar de mio Cid is “very cinematographic,” admits Porrinas, who says there were “evident concessions made for mushiness, fantasy and morbid drama.”

The scholar notes that none of the most famous episodes that most people think of when they think of El Cid actually happened. Instead, they were created much later. The duel with Jimena’s father, for instance, first became part of the story in the 15th century. As for making the king swear that he had nothing to do with his brother’s death, it was only in the 13th century that this episode was incorporated into tales about El Cid. In any event, it would have been impossible for a nobleman to thus defy the power of a monarch.

Diego, the son that so little is known about, is reported by historical sources to have died in battle against Muslim troops at Consuegra in 1097. “It was a severe blow for El Cid, who lost all hope of establishing a lineage that would perpetuate his hold on the recently conquered principality of Valencia, although he did manage good marriages for his daughters,” says Porrinas.

As for the famous scene showing a dead El Cid tied to his horse and striking fear into his enemy’s hearts, it is part of the legend created by the monks at the monastery of Cardeña, where Díaz was buried after his embalmed body was taken out of a Valencia under threat from the Almoravids.

Porrinas says there is no evidence that he was ever called Cid or Sidi (“lord” in Arabic) during his lifetime. “The first time we see that is in the Poem of Almería, dating back to the mid-12th century, where he is mentioned as Cid. This does not mean that his Arab soldiers or Valencian subjects did not call him that, but there is no documentary evidence of it.”

It may come as a surprise to many that El Cid was a mercenary. “It sounds pejorative, but that is the definition of someone who fights for money,” says Porrinas. “Rodrigo was very pragmatic and he understood that serving King Al-Mutamin of Zaragoza and his successors was the best way to achieve his own ultimate goal of taking Valencia. One cannot understand the Campeador without understanding his military, political and cultural relationship with the Muslims.”

Porrinas laughs when he is asked if a book like his could have been published under Franco. “Impossible. Francoism was devoid of ideology and it had to create one, and it appropriated symbols such as Don Pelayo, Covadonga, Agustina de Aragón and El Cid. Franco identified with the Cid of legend, and he liked others to see him that way too. He really made things easy for the shooting of the Charlton Heston movie, which globalized that epic image of the character.”

Looking back at El Cid, Porrinas says that “he did not change History with a capital H, but he did change cultural history.” The epic poem Cantar de mio Cid changed the history of Spain, and both Pérez-Reverte’s new novel and an upcoming Amazon Prime series have created renewed interest in Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar.

“It is a new Cid for these new times, but that does not mean that it is the definitive one or that everything has already been said on the subject,” notes Porrinas. “History is a living science, and El Cid will still be riding for a long time to come.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.