Deciphering the sex scenes in Spain’s medieval churches

Experts meet to discuss the meaning of highly explicit sculptures made 1,000 years ago

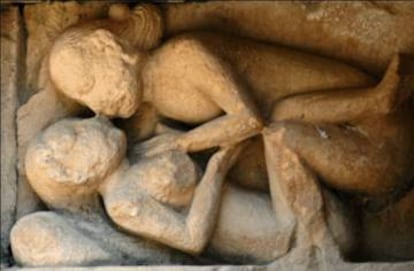

Why is that man showing off his enormous phallus, which seems to be pointing straight at us? What about that other bearded fellow who is apparently masturbating? And what is the meaning of that woman who is exhibiting her vulva? And is that couple really in the middle of intercourse?

These figures have all been there for nearly 1,000 years, sculpted into churches in northern Spain. They are in plain view on the façades, on the corbels that hold up the cornices, on the capitals crowning the columns, and even on the baptismal fonts.

But why did the stonemasons of the Middle Ages craft this cheeky iconography? What was the Roman Catholic Church trying to convey? A group of experts gathered inside the monastery of Santa María la Real in Aguilar de Campoo (Palencia) tried to answer that question last weekend at a seminar called “Art and sexuality in the Romanesque centuries.”

Unfortunately, there seem to be no clear answers. “How many interpretations are there of this eroticism? As many as there are people in this room,” said Eukene Martínez de Lagos, an art historian at the University of the Basque Country, pointing with her chin at the hundred-odd students sitting across from her on day one of the seminar.

The course included a field trip to four churches built in the medieval style known in England as Norman, and elsewhere as Romanesque, and which gradually evolved into Gothic architecture.

The most famous of these temples is the Collegiate Church of San Pedro de Cervatos, in Cantabria, which dates back to the 12th century. This northern region is home to the most relevant depictions of sex in Romanesque art, although other examples exist in eastern Segovia, in western Soria, in northern Palencia and Burgos, and to a lesser extent in other parts of Castilla y León, Galicia, Álava, Navarre, Aragón and Catalonia.

Not everything was darkness and horror in the Middle Ages

José Luis Hernando, Zamora Distance University

“The artists were organized into traveling workshops where there was typically one master and several apprentices, and they moved around depending on their commissioned work,” said Alicia Miguélez, of Universidade Nova in Lisbon.

Even today, it is striking to discover a man and a woman exhibiting their nudity on a capital right next to the altar inside the church of Saint John the Baptist, in Villanueva de la Nía. There are still traces of black paint on the woman’s pubis, while the man’s penis was cut off at some point during more demure historical times.

“Some people think it was meant as a lesson, as a representation of what not to do, explained in a forceful and explicit manner,” said another one of the speakers, José Luis Hernando Garrido of Zamora Distance University.

“That is a strange interpretation; it would be like giving a teenager porn magazines and saying: ‘look, this is bad,’”, retorted Jaime Nuño, director of the Romanesque Studies Center at Santa María la Real Foundation, which organized the seminar. Nuño tends to think that it was merely “a representation of daily life.”

Other experts posited that maybe it was an incitement to have children at a time when infant mortality was very high. There was yet another, more daring hypothesis put forward at the gathering. “Perhaps they were used as an antidote against evil, as some sort of lightning rod against the Evil One, who comes from above,” said Hernando. “It might have been something of a bear trap for the devil...although I’m still of two minds.”

The one thing that these sculptures could not possibly have been is a prank by the stonemasons, despite some belief to the contrary. “They were humble artisans, they had very little power of decision over decorative elements; those decisions came from the bishop or from the individual who was paying for the work.”

Medieval sex

The sculptures also provide insights into sexual relationships in the Middle Ages. “We erroneously believe that all sex was considered bad at that time. Yet doctors regularly prescribed sex as a way to keep a marriage healthy, and there was even some tolerance for members of the clergy who had relations,” said Paloma Moral de Calatrava, a historian at Murcia University.

Her remarks put the spotlight on an issue that was to divide the clergy and the medical profession: the Gregorian reform that established celibacy for members of the Church from the 12th century onwards, partly because of theological matters (“The sacrament of the Eucharist cannot be administered by someone who stains his hands with semen, considered impure”). But there were also economic concerns: clashes between the children of clergy members over their fathers’ assets could hurt Christian unity. As for the rest of society, the papal orders were clear: yes to sex, but only for procreation purposes.

Paloma Moral, an expert on women’s health during the Middle Ages, underscored that “the Church was forced to face the fact that monks and nuns were sexual beings.” Nuns suffering from “uterine suffocation” due to abstinence were allowed to masturbate, and were even allowed to use a primitive dildo. Medical records of the era written by doctors who were also members of the Church explained that this substitute for the male organ must be “delicate, crafted out of saltpeter, wax and watercress.” Monks, who did not suffer from this condition, were not allowed to relieve themselves.

The final message of the seminar was that “not everything was darkness and horror in the Middle Ages,” said Hernando. “Nor have we made that much progress on some matters of sexuality,” added Moral.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.