Could a 1933 novel about Nazism provide a cautionary tale about totalitarianism in 2022?

‘The Oppermann Brothers’, Lion Feuchtwanger’s seminal book about the German Reich, has been republished in the US to great acclaim

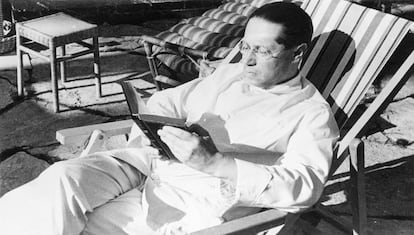

Lion Feuchtwanger was one of the many Germans who saw their world fall apart with the rise of Nazism and Hitler. Feuchtwanger was a well-known pacificist who gained broader fame for his 1925 novel, Jud Süß (The Jew Seuss, in English), a virulent denunciation of anti-Semitism. Intelligent and free-thinking, Feuchtwanger was Jewish, leftist and anti-military – everything the Nazis hated. In 1933, he undertook a long and dangerous trip into exile and initially settled in the south of France. When the Germans invaded in 1940, he fled once again, this time to California. There he met Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann, like-minded German exiles who had also settled in Los Angeles.

The novel that put Feuchtwanger squarely in the sights of book-burning Nazis was The Oppermann Brothers, the 1934 story about a German Jewish family that quickly made an enormous impact. It was almost immediately translated into 10 languages and sold 250,000 copies. At the time, the German government was energetically rolling out its anti-Semitic policies and had already opened Dachau, its first concentration camp. Persecution of Social Democrat and Communist party members was commonplace. But many leaders of other countries remained unconcerned, and considered communism to be a greater threat. In fact, the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin attracted widespread international participation. Early on in Hitler’s rise to power, many Germans thought he could be controlled, but Feuchtwanger’s book showed that no one was safe from the murderous madness of the new regime.

Anyone who reads The Oppermann Brothers today will be shocked by Feuchtwanger’s acute descriptions of how Nazism persistently crept into every corner of life. The inescapable conclusion of the book is that no free-thinking citizen could remain in Germany, and that the persecution of the Jews would never stop. Few people so clearly intuited and foretold the Holocaust and World War II. In one of the book’s many plotlines, a student of the Oppermanns reads his essay in class out loud. “Luther’s translation of the Bible and Gutenberg’s inventions were undoubtedly far more important for Germany and its reputation than the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest,” (when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed and defeated Roman legions in AD 9). A teacher sympathetic to the Nazis (whom Feuchtwanger calls “the populars”) denounces the student to the French high school principal, who comes to his defense.

The Nazi-sympathizing teacher declares that Oppermann is not a “good German,” nor can he ever be. Without revealing too many spoilers, when Hitler comes to power, the principal is forced to choose between his job and poverty, at best. More likely, he would be beaten and thrown into a concentration camp. To choose his job over these other fates would mean deserting an excellent pupil with whom he agrees.

“History taught me how incredible it was that besieged people only considered escaping to safety when it was much too late,” says the book’s narrator. That’s the lesson in a nutshell – persecuted people realize that it is no longer possible to escape, and people who thought they were being governed by a democracy suddenly realize that it’s actually a terrorizing dictatorship. While nothing compares with Nazism, this lesson has all too obvious contemporary echoes – would Brazil have remained a democracy if Bolsonaro won a second term? What about the United States if Trump wins the presidency again in 2024? Are Hungary and Poland dictatorships right now? Can Italian democracy survive Meloni? Will the rights of the most vulnerable minorities be protected?

The Oppermann Brothers has recently been republished in English (Simon & Schuster, 2022) with a foreword by Joshua Cohen, who won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his genre-bending novel, The Netanyahus. The book has rekindled the debate on whether Feuchtwanger’s 1993 story can be applied to the present, a warning from the past about the anti-democratic forces that are doggedly gaining ground in Europe and the United States, while we naively think that our democracies are too strong to be defeated from within.

In his foreword, Cohen writes that The Oppermann Brothers is evidence that a cautionary tale can echo beyond the immediacy of its time if written with honesty, great dramatic skill, and deep feeling for human beings. One of the most disturbing aspects of the book is how closely it describes a world ruled by the likes of Vladimir Putin and Daniel Ortega, a world in which true and false have no meaning. “The fog of lies thickened more and more over Germany, given over to the lies that the populars spread day after day in millions of ways, shouted from loudspeakers and on printed paper. He had founded a special ministry for this purpose. With the most modern technical means available, the hungry were convinced that they were satiated, the oppressed were told that they were free, the threatened were persuaded that the whole world envied them for their vitality and glory.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.