Baldness was funny, blindness was not: Mary Beard unveils humor in Ancient Rome

In a new book, the Cambridge scholar analyzes how laughter help us understand Roman society

The cast of Monty Python made it very clear in their movie Life of Brian what the Romans had done for us. “The sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a freshwater system, and public health.” Mary Beard, professor of classics at the University of Cambridge, adds one more thing: humor and jokes. In her book, Laughter in Ancient Rome: On Joking, Tickling, and Cracking Up, Beard tries to explain what the Romans laughed about and explores whether we have inherited their sense of humor. She also considers whether jokes can be a way to understand the society of ancient Rome.

One of Beard’s conclusions is that, while there are jokes that now seem to us pretty absurd and distant, many others that were circulating back then are still popular today. The stones of the Coliseum in Rome or those of the aqueduct in Segovia, Spain, have survived nearly 2,000 years, but so have the laughs. For example, “a guy goes to the hairdresser and he asks him, ‘How do you want me to cut your hair?’ And the guy replies, ‘In silence’.” There are a number of versions of this next joke – which was reportedly the favorite of Sigmund Freud – but it also dates from the classical world: “The king meets his double and says, ‘Did your mother work in the palace?’ and the double says, ‘No, but my father did.’”

Given that (fortunately) urine is no longer used as an essential element to leave clothes clean in a laundry, as was the case in ancient Rome, some Roman jokes are difficult to understand. For example: “A meanie went into a fullery, and not wanting to pee, died.” Not even Beard can find a logic to this one, and offers this explanation. “Possibly (and this is the best explanation I can offer) the mean man was so keen not to give his valuable urine to the fuller for free that he retained it until his bladder burst and he died.”

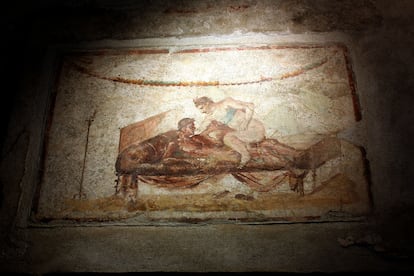

Thanks to classical historians such as Dion Casio, but also to a compilation of ancient jokes that has survived, Philogelos (The Laughter Lover), which is a joke book dating from the fourth or fifth century, we now know that the Romans laughed about alopecia but not blindness, that they would make jokes about crucifixion or patricides, and that emperors such as Commodus or Caligula had a very dark sense of humor. Suetonius offered an example of the kind of jokes that the latter tyrant would make. During one of his sumptuous banquets, he began to guffaw. Asked about what had made him laugh he replied: “What do you suppose, except that at a single nod of mine both of you could have your throats cut on the spot?”

“I believe that humor always is related, in part, to power,” explains Beard, 67, via an email interview. “You can very clearly see the jokes around the emperor. Bad emperors used jokes to humiliate others, like Caligula in this case. The good emperors enjoyed their friendly jokes with their people and could accept any joke made in the appropriate spirit. But it goes further than that. Just like us, the Romans used humor to classify outsiders. For example, the inhabitants of Abdera [an ancient port in Spain] were amusingly stupid.”

One of the questions posed by the book (which was originally published in 2014 and has just been released in a Spanish version) is that studying humor allows us to understand Roman society, even though a part of the population – slaves, but also to some extent women – are overlooked. And, at the same time, it’s a mirror into which we can gaze to study our own society.

In the epilogue, the author recalls a conversation in a café in Berkeley with another classicist, Erich Gruen, who had been reading about many of the themes touched on by Beard at her conferences since he was a student. She asked whether we could ever find a joke about crucifixion funny. Gruen responded by saying that the surprising thing about Roman humor is not its rarity, but rather that 2,000 years previously, in a radically different world, we can still laugh at some of the jokes that cracked the Romans up.

Asked about what jokes about Rome can teach us, Beard replies: “What makes different cultures laugh takes us directly to their relationships with power and their concerns. It has often caught my attention the way that Romans laughed at questions of mistaken identity (how to know who someone is), much more than us, even though this is still an element of some comedies. I’m sure that its importance in Roman culture is related to a major problem in a world without ID documents: how can you be sure that someone is who they say they are? Laughs can also take you to a popular world that is rarely glimpsed. It seems, for example, that the Romans found baldness funny, but thought that it was cruel to laugh about the blind.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.