A Spanish hamlet pins hopes of prosperity on its Roman Empire legacy

Villar de Domingo García, population 218, is home to an astounding archaeological site containing the largest figurative Roman mosaic found to date

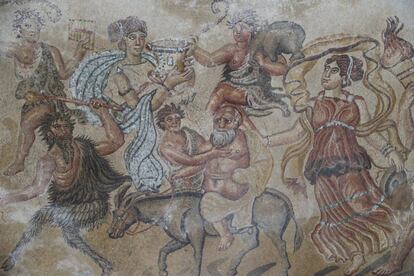

Once upon a time, there was an immensely rich man. He was so wealthy that he could afford to have wine sent from Syria to his home, nearly 5,000 kilometers away, even though this was back in the fourth century, in Roman Hispania. His estate, known as Villa de Noheda, was a testament to his great power: it covered more than 10 hectares, according to recent geo-radar measurements. Just his dining room (known in Roman as a triclinium) was 291 square meters, and it was decorated with mosaics fit for the palace of an emperor.

“This man really existed,” explains Miguel Ángel Valero, professor of ancient history at the University of Castilla-La Mancha. His name is not yet known “but sooner or later, we’ll find out,” says Valero, who has spent a decade uncovering the dazzling features of the villa, which is located in Villar de Domingo, a hamlet of 218 inhabitants in Cuenca province, in the central region of Castilla-La Mancha.

It’s unique in the world. When I show the photos in international congresses, specialists from other countries are astonished

Archaeologist Miguel Ángel Valero

The regional government is now planning to open the archaeological site to the public. While only 5% of Villa de Noheda has been excavated, researchers have already found the largest collection of marble sculptures in Roman Hispania, featuring more than 500 large fragments, and the largest figurative mosaic in the entire Roman Empire.

The mayor of Villar de Domingo García, Javier Parrilla, of the Popular Party (PP), wants the opening of the site to coincide with a new campaign of archaeological work scheduled for the summer, which will include the excavation of the villa’s reception hall. This room “is normally bigger than the triclinium,” explains Valero.

Villa de Noheda was discovered more than a decade ago, when a tractor hit a hard spot of land in the village. This area had been nicknamed The Stony Field (El Pedregal) after the numerous stone blocks and metal objects that kept turning up there. When the tractor dug up the ground, it pulled up hundreds of small, brightly colored stone pieces – they were part of the tiles of the mosaic. The discovery prompted archaeologists to begin excavating the site.

What they found far exceeded all expectations. Noheda is a mammoth residential complex that mixed “business with pleasure” within a large estate (fundus). The fundus – which covered more than 80 square kilometers – was made up of crop fields (ager), pastures for livestock (saltus) and a mountainous area (silva) where wood could be harvested. The villa was located far enough away from the Roman road so as to not be detected by unwanted visitors or attacked by hungry legions.

The decorative paintings, floor mosaics, sculptures and other ornamental elements highlight the great wealth of the owner. Researchers have found more than 30 types of marble brought here from all corners of the known world at that time, and they are still unsure how it was possible for the landowner to acquire such wealth. “The dominus [Roman landowner] could have been connected to the emperor, who at that moment was Theodosius I, we don’t know yet, but it is clear that he belonged to the high aristocracy,” explains Valero.

The best is yet to come, because we have only excavated a small part

Archaeologist Miguel Ángel Valero

The mosaic in the villa’s triclinium is the largest figurative mosaic of the Roman Empire known to date. It is comparable to the famous Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina in Italy (which is slightly smaller, 270 square meters) and is made up of “innumerable” tiles. In each 25-square-centimeter area, an average of 1,243 tiny tiles were used, some measuring just a few millimeters.

Given the scale of the work, archaeologists believe there was not just “one pictor imaginarius [designer],” but several. They also discovered that some areas of the large mosaic were covering a previous one. “It’s as if the owner of the villa didn’t like the first result and ordered to have a different one made on top. Money was not going to be a problem,” jokes Valero.

As well as the mosaic, archaeologists have also excavated “550 large sculpture fragments, made from marble imported from the East and from Carrara [Italy]. It is the largest sculpture set in all of Hispania, and includes the figures of Dionysus, Venus and the Dioscuri,” adds Valero.

His fair share

José Luis Lledó, the most recent private owner of the land where the mosaic was discovered, has turned to the courts to demand what he views as his fair share of its value. The property underwent expropriation by the municipality of Villar de Domingo García in 2013, and Lledó was offered €7,500 for the five hectares of rural land. But he is asking for €48.9 million.

A regional court in Castilla-La Mancha found in December that the matter is unclear at several levels: whether it is even possible to set a price to the world’s largest Roman figurative mosaic; whether the owner of the land should be compensated even though the mosaic has Cultural Asset Designation; and if so, whether the money should go to the owner or to the driver of the digger who found the mosaic in the 1980s. Further complicating the matter is the fact that the discovery was not reported until nearly 20 years after the fact.

It is now up to the Supreme Court to decide. In 1992, this same court ruled in favor of a shepherd from Cádiz who “started to scratch the earth to pass away the time while his flock grazed” and found a Roman mosaic. The shepherd received half of the mosaic’s value, and the property owner the other half.

So how did the luxury villa come to be forgotten? The fall of the Roman Empire sparked the rapid Christianization of all of Hispania. The pagan sculptures were destroyed and thrown in a dump. Part of them was used to make marble dust, but many survived. Archaeologists are now trying to piece the fragments back together like a jigsaw puzzle. Some have been recovered and are now on display at an exhibition in Cuenca titled Noheda: the image of power.

“Now what’s left is to be able to show the site,” says Parrilla, the mayor of Villar de Domingo García. “Everything is almost ready for its opening, as well as an information center in the village. The idea is for visitors to enjoy this while they watch the archaeologists at work.“

The hope is that the site will attract visitors to the hamlet, which often loses tourists to the nearby city of Cuenca. Local authorities and researchers have been giving courses and hosting activities with the locals to get them involved in what could become a big tourist and cultural attraction.

Sources from the regional government confirmed to EL PAÍS that Villa de Noheda will be opened to the public “as soon as possible.” “It’s unique in the world. When I show the photos in international congresses, specialists from other countries are astonished. And the best is yet to come, because we have only excavated a small part,” says Valero with a big smile.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.