All the drama of Spain’s flash floods, contained in one street: ‘Deaths could have been avoided’

The water destroyed Nuria’s house, Sarai’s clothing shop, Maria’s school. Five residents died in a 300-meter stretch of road in Catarroja, one of the hardest hit municipalities in Valencia province. We focused on this spot, where events reflect the magnitude of the disaster: the failure of the alerts, the lost homes and businesses, the delay of the emergency services, the tide of volunteers. And the glimmer of hope for the future

Car horns started honking and dogs began to bark. That’s the first thing that Laura Jiménez and Vicente Cantador remember. Then they heard the sound of water. But it wasn’t falling from the sky, because not a single raindrop fell that afternoon in Catarroja. It was coming from the ground. “It’s the ravine that has overflowed,” they thought. They saw a tongue of water, small at first, advancing from the far end of the street towards their building door. They ran down from the first floor where they live and hurried to get their car out of the underground garage. There was a rush of water. In the space of just two minutes, chaos ensued. With some of the neighbors, Vicente raced to erect a makeshift dike at the garage door using trash bags. Then the lights went out at number 7 on Blasco Ibáñez Avenue. Vicente went back upstairs to calm down his son, who was crying. They heard screams and banging. Everything was dark.

He soothed the boy and went back downstairs. The water was now rushing by with unstoppable force. Except it wasn’t quite water. It was a brown, viscous mass carrying stones, trees, debris, wood and objects of all kinds. It was then that some of the people who were erecting the dike were swept down into the garage, and nobody could do anything to stop it. Two days later, the Spanish Army’s Military Emergency Unit (UME) removed four lifeless bodies from in there. Many neighbors still cannot bring themselves to talk about what happened. “I never want to remember that night again in my life,” says one of them.

Catarroja, located five miles (eight kilometers) from the eastern Spanish city of Valencia, has a population of nearly 30,000. It is one of the municipalities most badly affected by the October 29 flash floods, which have caused at least 215 deaths in the province and destroyed dozens of villages. It is an area of orchards and marshland nestled between Paiporta, Benetússer, Albal and Massanassa, four names sadly famous these days for being located in ground zero of the flooding. All these towns are stuck together, and if you are not familiar with the area, you don’t know where one ends and the next one begins.

The degree of devastation in all of them is such that it leaves you breathless. In many streets, there is only mud and human beings with stories to tell. Each person has one. What happened here is so brutal that we journalists have been left to wonder whether it is even possible to convey the tragedy in all its dimensions. Sometimes it is useful to look through a microscope, so this report focuses on a single street in Catarroja, the street that Vicente and Laura live on, the street where four people died in that garage. On Blasco Ibáñez Avenue.

It is called an avenue, but in reality it is not a very big street, stretching barely 300 meters. It contains about 200 housing units, the Larrodé school, the Berenguer Dalmau public secondary school, a hair salon called Azabache owned by Pili, a clothing store called Lola Guarch owned by Sarai and her mother María, a block of three-storey white houses, a park for children to play in, two restaurants — Pasta Nostra and 11 de Calle — a bar called Marjal, Laura and Vicente’s house, Pedro’s, José's, Nuria’s... And at the far end, although formally it belongs to another street, there is the San Vicente Mártir funeral home. Just behind it, a minute’s walk away, is the ravine known as Barranco del Poyo. When the water level is low, it looks like the harmless bed of a calm river. But it is one of the natural waterways that overflowed torrentially, and this street was one of the first to receive its violent brown tide.

Now, everything is destroyed. The gym hall of the Larrodé school has become a food and basic goods distribution center run by teachers and parents in the only part of the facilities that has remained in good condition. The cafeteria is a mess of mud and tables. The kindergarten classrooms were flooded. The little backpacks with the extra sets of clothes and the coat racks with photos of the children among smiling bees and hippos are now covered in mud. The Berenguer Dalmau secondary school is closed and its courtyard is full of rubble and buried cars. Someone entered the building and ransacked one of the offices, leaving documents and graduation photos of former students lying strewn on the floor.

Nuria, her husband and her children, who live right across from the secondary school, no longer have a home. Pili does not have a hair salon. Sarai and her mother have no boutique left. Behind the funeral home there is a coffin full of mud. Laura and Vicente feel an anguish that will not go away. Everyone on the street is in shock. But they are pushing forward and have been working day and night for 12 days, with the help of a tide of volunteers, to recover their lives amid the mud and a putrid smell that permeates everything, that filters inside your brain and will not go away. The story of the flash flooding that followed a record deluge is contained entirely in this street in Catarroja.

1-THE FLOOD: “A night of horror and screams in the dark”

“It was terrifying.” “I had never been so scared.” The memories of the residents of Blasco Ibáñez Avenue coincide in that Tuesday, October 26, was the worst day of their lives. “You outsiders have seen the destruction and the mud in pictures, but you cannot imagine how scared we were that night,” says Sarai Gil, 29, who was in her fashion store that day, working among fabrics and dresses. They all tell the same story: that it happened very quickly, that things were quiet, then they saw a little water, and all of a sudden the water reached up to their necks. Quite literally, in Sarai’s case. She got out of the store as best she could and the neighbors pulled her up to the first floor.

“Words cannot express the horror of that night of screams in the dark,” she recalls. “Imagine: no light and no way to call anyone. Incommunicado. All the store shutters were bursting. The flood water was very loud. From the balconies we could see cars floating by, as if our street were a river. But the worst thing was the constant screams of people calling for help. It is something we will never forget. You listened to them helplessly, not knowing if anyone was helping them or if they were dying.”

“It was, without a doubt, the most distressing night of my life,” says Nuria Cabezas, 35. She was smoking a cigarette on the balcony and typing on the computer. She lives on the ground floor at number 36. Her husband had gone out and her three teenage children were inside the house when she noticed the water coming “with tremendous force”: “It was beastly; I told the kids to run to the neighbors’ house. From then on everything was horrible. The windows in the courtyard began to shatter. There was a corpse down here that was carried away by the current. It wasn’t until Thursday that I found out whether my husband was dead or alive. I have cried so much that I have no tears left.”

From the next day onwards, residents have had to deal with the damage to their homes, businesses, cars, streets… but that night, it was their lives that were at stake. Many people struggled to hold on to anything they could — a fence or a bedsheet that somebody threw down at them. Others remained perched for hours on top of anything halfway stable, like a garage door. From their balconies, mothers and fathers lit up the streets with flashlights so that their children could hold on to something and try to make their way back into their houses by any means necessary.

The less fortunate, like Vicente and Laura’s neighbors, died. The firemen are still pumping water out of the garage because there is still a part of it that is still flooded, although they have gone inside with zodiacs and believe that they will not find any more dead people. “I hope so,” says Vicente. “But besides the four people they found, I saw two young people on the garage ramp. The girl must have been about 20 years old, she was wearing shorts and she looked at me with eyes that will stay with me for the rest of my life. I was shining my mobile phone on them, but I couldn’t help them. They were swept inside. I want to believe that they managed to save themselves somehow.”

“The most absurd thing of all is that when there were already people drowning and we were all trying to save our lives, that’s when we received an alert on our cell phones telling us to avoid travel because of the heavy rains,” he recalls. “The fucking alert.”

The alert read: “Civil Protection alert due to heavy rains; as a preventive measure all types of travel should be avoided in the province of Valencia. Stay tuned for future warnings through this channel and official sources, on X@GVA112 and on À Punt.”

Everything about that alert was wrong. The À Punt regional TV channel could no longer be seen or heard: there was no electricity, no phone reception, and, at that point, nothing at all. There had been no rain whatsoever on Vicente and Laura’s street; instead, a ravine had overflowed, which is quite different. And the four people who died in that garage were not traveling anywhere. They were only trying to protect their cars because they had no idea of the magnitude of what was coming and thought it would be just a small overflow, like so many others experienced in the past by people living in houses built in an area prone to flooding. Nobody had warned them. They did not risk their lives for a car. They just lacked information, and everything happened in a matter of minutes.

Luis, who lived just a few meters down the street, had not been traveling either. He was an elderly man who lived all by himself in a white three-storey house. He had suffered a stroke, had mobility problems, used a walker and always stayed on the ground floor. He was at home, feeling safe, when the water came in. When it started, a neighboring couple called the emergency number 112 to report that there was a person who could be in danger. “We rang several times, but nobody answered the phone,” recalls Pedro Díaz. They could not do much more than that. Pedro is 71 years old. His wife is 70. It was all they could do to try to save themselves. The next day, Luis’ daughter found his body in the house.

At least five people died that night on Avenida Blasco Ibáñez, out of a total of 215 counted so far in the province of Valencia, according to the latest available data. The main cause of death, according to one of the forensic experts working in the affected areas, is asphyxiation by water and mud. Besides homes and garages, lifeless bodies have been found in streets, in fields and on roads. Some victims died from a blow caused by an object due to a flood that swept away everything in its path with great force.

The timing of the official phone alert is an emotional trigger for all the neighbors. There is no one here who does not say angrily that Valencia’s regional government, led by Carlos Mazón of the conservative Popular Party (PP), minimized the risk; that officials had information in their power but did not give it out; that the more than 200 deaths, or at least some of them, could have been avoided. On this street, it is a fact that the alert arrived late and that it was of no use. If those five people had known that there was a risk of flooding and that it could be of that magnitude, Luis could have gone up to an upper floor, and the deceased in the garage would not have gotten into that death trap. But for that to happen, the warnings should have been much more forceful, and they should have indicated that the seriousness of the danger was extreme.

“What they should have said was that the risk was due to the overflow of the ravine, not to rain,” says Vicente. “Because we were looking at the sky and not a single raindrop fell here. We thought that the storm was not reaching Catarroja. But did it ever.” “The destruction of buildings and things could not be avoided, but many deaths could have been avoided,” agrees Nuria. “Many people could have been saved with information. Authorities were under the obligation to have it and give it to the population. I do not understand how this could have happened. What kind of management is this?”

“Local authorities should have gone all over town with loudspeakers warning us that the ravine could overflow, that it was very dangerous,” adds Juanma de la Cámara, a 59-year-old who lives on number 32, Blasco Ibáñez Avenue. The problem is that town halls had no information either. “The Generalitat [regional government of Valencia] didn’t give us any warnings about anything all day,” says Lorena Silvent, the Socialist mayor of Catarroja. This is her account of what happened that day:

— We knew by Saturday that we were in an area that could be affected by floodwaters, but nothing more. I activated the emergency work group to check the sewers, watch for leaks... That morning [Oct. 29] we found out that it had rained in the Ribera area and we started to talk to other mayors to see if we should cancel classes. We did. We canceled classes from 3p.m., but only as a precaution because of the road travel that classes entail. We had no warning of any kind from the Generalitat about the evolution of the flood, and it wasn’t raining here. We were working without information. I don’t know how much it rains or what happens in other areas because I’m not in contact with the Hydrographic Confederation [water management public agency]. Just in case, I sent a local police patrol near the ravine. At 5:30 p.m. everything was very calm. At that point, the water was not even a meter high. But shortly afterwards someone from a company called the police: “Hey, there’s water here.” And from then on everything happened so fast that there was no time for anything. At around 6:30 p.m. the ravine began to overflow and at 7 p.m. the chaos and destruction began.

That sentence, “it all happened so fast that there was no time for anything,” is repeated by everyone on Blasco Ibáñez Avenue. José Maestre was shopping at the Mercadona supermarket around the corner. “José, go home, something strange is happening here,” the cashier told him. When he walked out of the premises, the water barely reached the curbs of the sidewalks. By the time he reached his door, just 140 meters away, the neighbors were already trying to build the dike outside the door of the garage where four people later died.

Rosa Manzanares, Juanma’s wife, was caught out in the street. She was driving to her pilates class when someone shouted at her: “Turn around, the wave is coming.” Drivers ended up leaving their cars whereve they could and running away on foot. “The water was coming towards us dragging containers, cars, it swept everything away… People were climbing on car hoods. Everyone did whatever they could. Luckily I managed to reach Town Hall, and I was able to warn Juanma before we were cut off, and I spent the night there along with several dozen other people.” Mayor Silvent remembers it well: “We rescued as many people as we could and sheltered them here. There was a young pregnant woman, elderly people, people with panic attacks. There was no electricity or communications. No one could call their family. It was dramatic.”

Meanwhile, during those key hours of the early afternoon, when there was already a local patrol watching the Poyo ravine and the disaster was about to begin, what was going on in the Valencian government? At 5 p.m. the meeting of the Emergency Center (Cecopi) had begun, but the Valencian premier, Carlos Mazón, was not there. Instead he was having a long, drawn-out lunch with a journalist, allegedly to offer her the position of director of the regional public television channel, À Punt. At that point, Utiel and other towns had already been flooded; the emergency military unit UME had been dispatched at 5 p.m., the mayors of affected municipalities were very nervous and did not know what to do, the national weather agency Aemet had launched a red alert hours earlier over the risk of a DANA (name given in Spain to an upper-level low that meets warm air from the Mediterranean and can cause severe rains, especially in the autumn); and the Júcar Hydrological Confederation had sent emails to the regional government’s emergency services warning of the situation in the Magro and Júcar rivers. But Mazón was still at his lunch. He joined the Cecopi meeting at almost 7.30 p.m., when Blasco Ibáñez Avenue was already completely flooded and destroyed, as were many other streets in the 65 municipalities in the province of Valencia affected by the flash floods. By the time alerts began to be sent out at 8 p.m., it was already too late for everything.

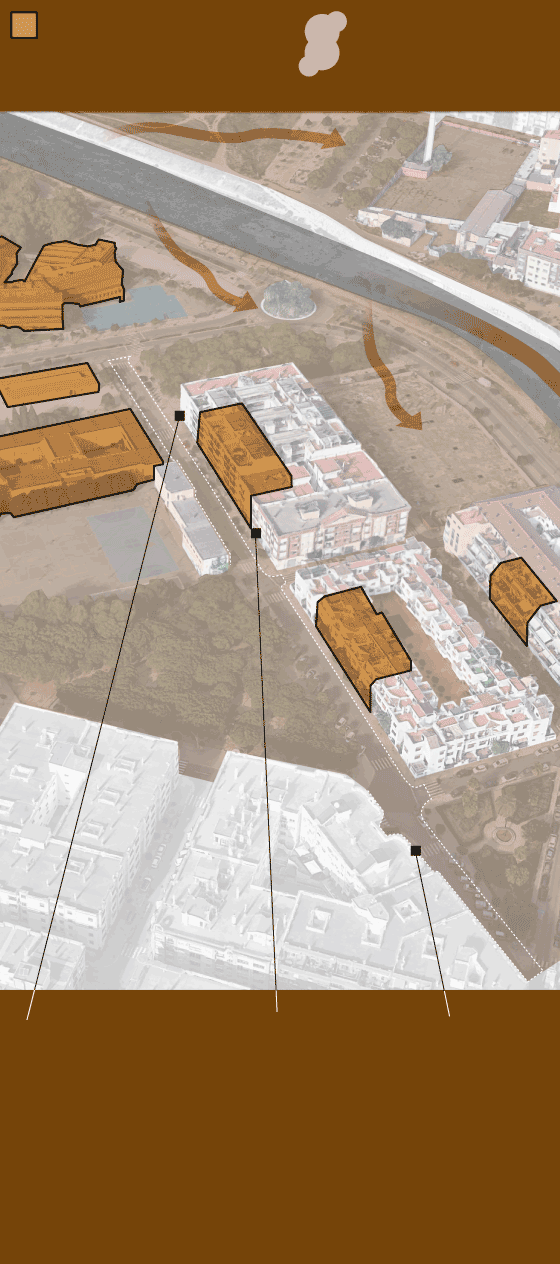

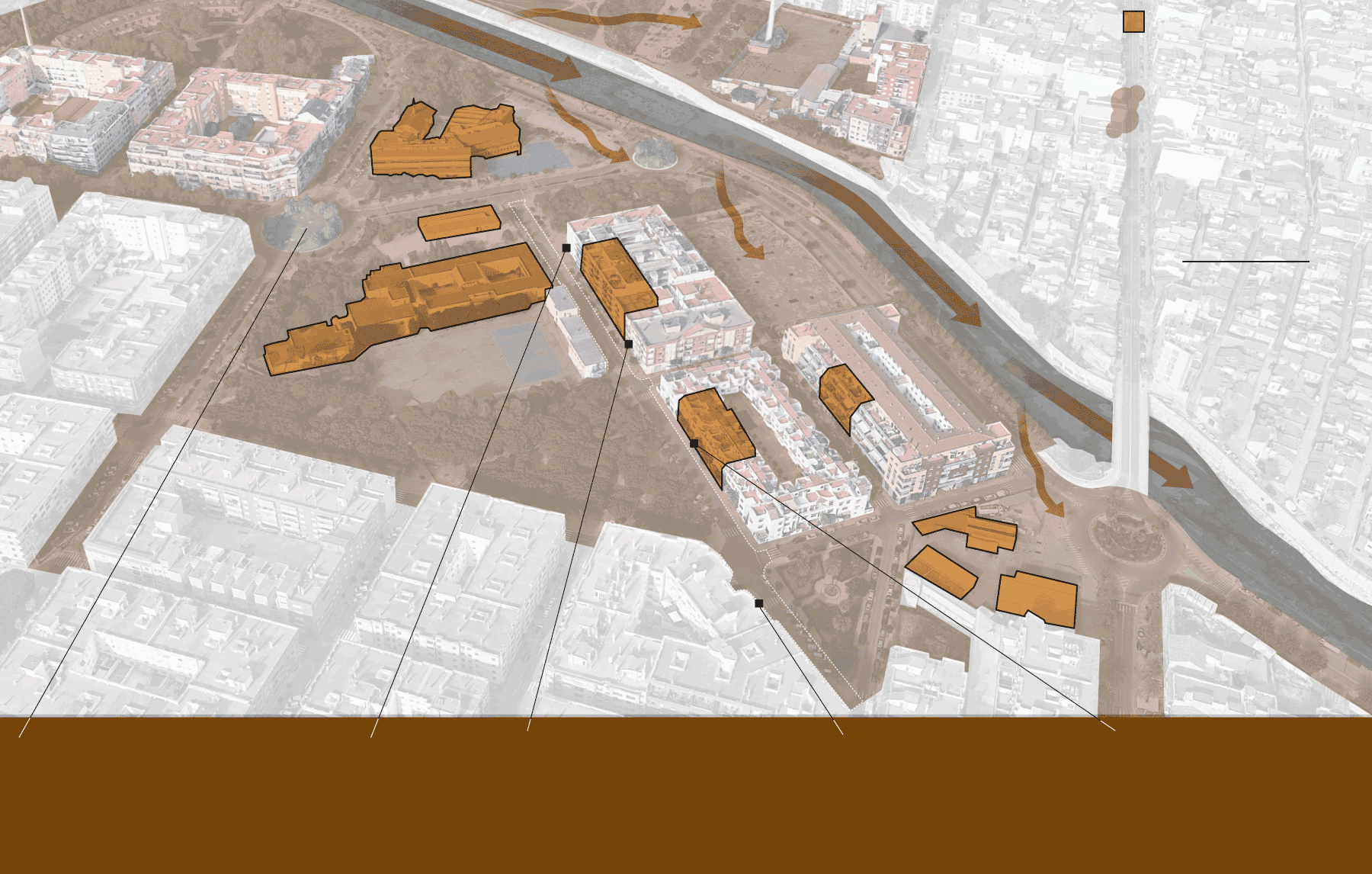

Damaged

constructions

Remains

of flooding

Larrodé

School

Barranco del Poyo ravine

Ronda Nord

36

32

Berenguer

Dalmau

School

Av. Blasco Ibáñez

7

CATARROJA

Home of

Nuria

Cabezas

Azabache

hair salon

and Lola Guarch

clothing store

Cuatro

muertos

en un

garaje

Source: Copernicus and in-house

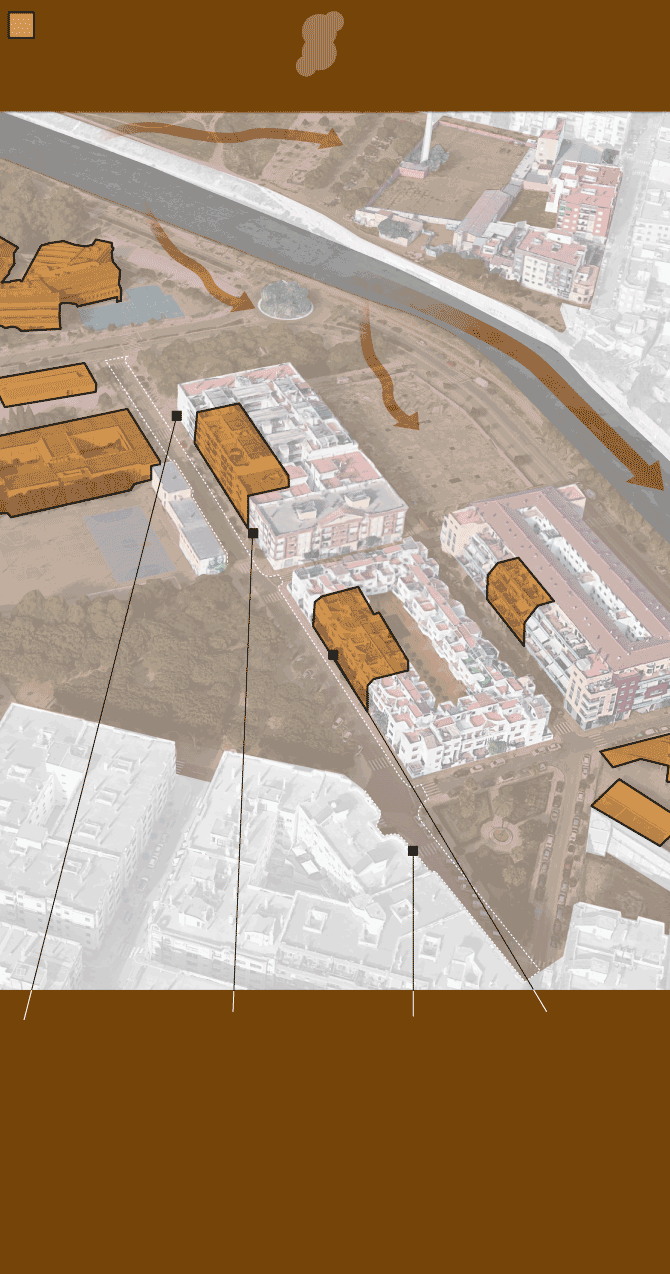

Damaged

constructions

Remains

of flooding

Larrodé

School

Barranco del Poyo ravine

Ronda Nord

36

32

Berenguer

Dalmau

School

Av. Blasco Ibáñez

20

7

CATARROJA

Home of

Nuria

Cabezas

Azabache

hair salon

and Lola Guarch

clothing store

Four

dead

inside

a garage

An elderly man

drowned inside

his house

Source: Copernicus and in-house.

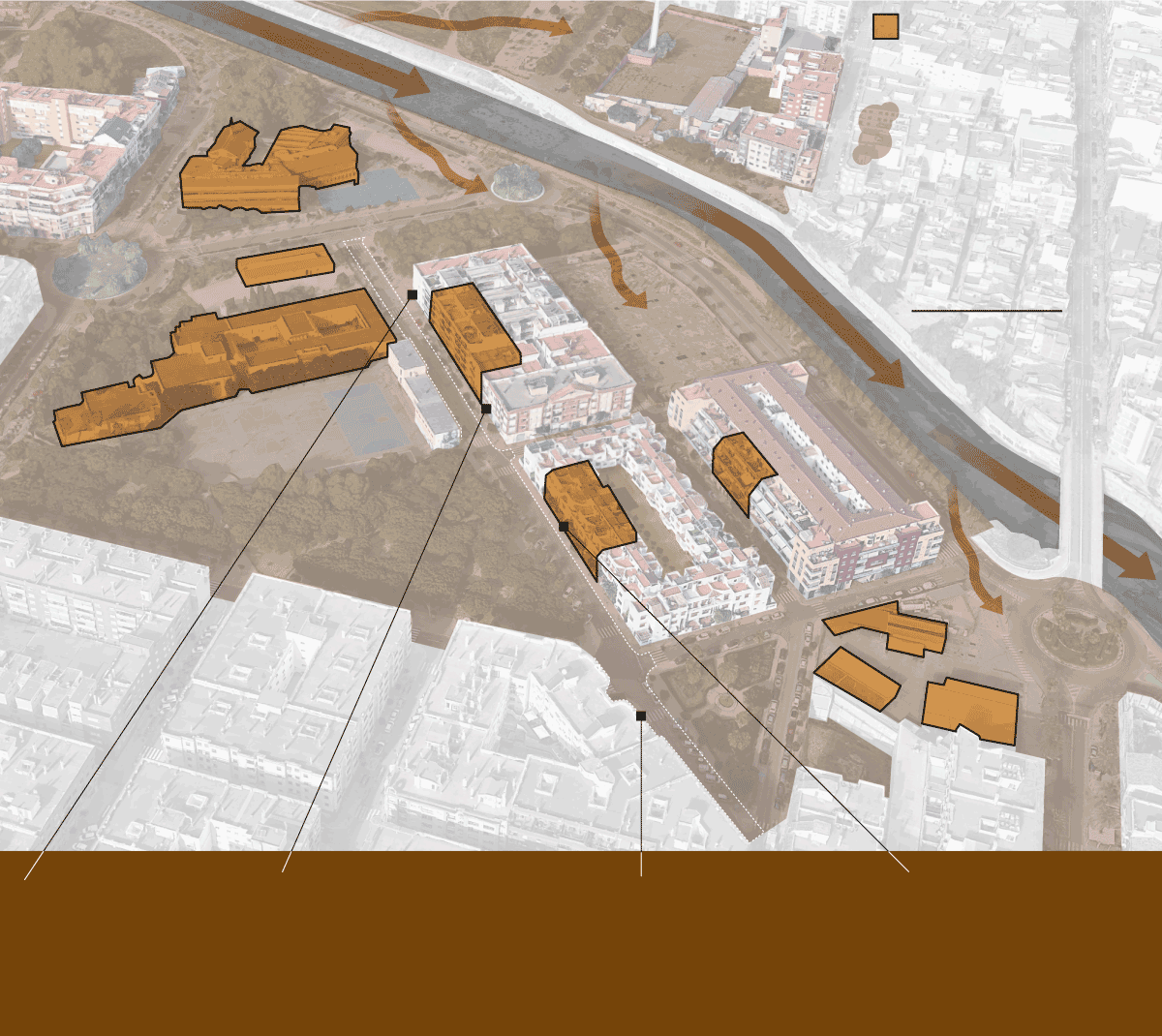

Damaged

constructions

Barranco del Poyo ravine

Church

Remains

of flooding

Av. Vicent A. Estellés

Larrodé

School

Ronda Nord

36

50 m

32

Av. Ramón y Cajal

Berenguer

Dalmau

School

Av. Blasco Ibáñez

20

CATARROJA

7

Home of

Nuria Cabezas

Azabache hair salon

and Lola Guarch clothing store

Four dead

inside a garage

An elderly man

drowned inside his house

Source: Copernicus and in-house.

Damaged

constructions

Barranco del Poyo ravine

Church

Remains

of flooding

Av. Vicent A. Estellés

Larrodé

School

Ronda Nord

36

50 m

32

Av. Ramón y Cajal

Berenguer

Dalmau

School

Av. Blasco Ibáñez

20

CATARROJA

7

The school is used

as a support center

Home of

Nuria Cabezas

Azabache hair salon

and Lola Guarch clothing store

Four dead

inside a garage

An elderly man

drowned inside his house

Source: Copernicus and in-house.

The scale of the disaster is brutal: 530 square kilometres were flooded and it is estimated that the damage has affected 190,000 people and 7% of the buildings in the province. Insurance claims have already been filed for more than 70,000 cars and 33,000 homes, according to the registrars. A third of the province’s companies, 54,000, have been affected to a greater or lesser extent: 355,000 workers, 51,000 self-employed and 63 business parks or industrial estates, according to data from the Chamber of Commerce.

2-THE DAY AFTER: “My whole life has gone with the flood”

When dawn broke on Wednesday, October 30, nothing was the same. Those who managed to get some sleep woke up and looked out from their balconies. Blasco Ibáñez Avenue was a post-apocalyptic scene of cars, wood and mud. At number 7 they knew there were corpses in the garage. There was another one further on, at number 22. They had no electricity, no water, no gas. Both schools were gutted, as were all the commercial premises and the apartments located on ground floors. That same morning they began to remove mud from the doorways so they could walk out into the street and start cleaning up, but wherever they looked, the mess seemed impossible to fix. Despite everything, on this street and on many others, the same phrase is heard again and again: “We are safe, we are still alive, and that is the only important thing.”

“We had to go and live with my in-laws,” Nuria explains. “On the one hand you feel very lucky to have survived, but we have lost everything. A house is a refuge. I am going through a period of depression, and this was the only place where I felt good. Now there is nothing left.” They have had to throw away their clothes, the new sofa, the dining table, the printer, the computer, the documents, the photos, the contents of the children’s rooms.

When the store owners first opened their shutters, the sight was devastating. “We had €100,000 to €150,000 worth of goods in here,” says Sarai, standing inside the fashion boutique she opened with her mother 12 years ago. They are giving everything up for lost, although they are trying to save the fabrics they love the most inside black tubs, even if they don’t know if they will succeed. “At most we might save 1% of what we had,” she says. “We also had an online store, but of course, now there is nothing to sell.” Inside the shop, only the ceiling lamps that were not reached by the water remain intact. The floor is full of hats, skirts, boots, dresses and shirts so dirty that it is difficult to guess what colors they used to be.

This is what the street looked like before and after the flash floods

At the Azabache hair salon next door, Pili is cleaning up with her husband, Juan José, and her daughter Noelia, aged 17. She doesn’t think she will be able to save anything. Not even the hair dryers which, as they are mounted on the wall, she thought might have survived. “I set up this hair salon 20 years ago,” she says. “It was my life, and now I don’t know if I’ll be able to open again. I have to replace absolutely everything. I’ll only be able to do it with a lot of help.” Washbasins, armchairs, dressing tables... “Only the floor has held up, miraculously. It all seems like a dream, or a nightmare, rather. You’re here but you’re not. We’re in a huge state of shock.”

The pace of work the street is frenetic. A week has elapsed since the flooding and people are still taking out unrecoverable belongings that are piling up while other people remove mud and more mud with shovels. Seeing these mountains of rubble is very sad. There are washing machines, brushes, tables, sofas, chairs, armchairs, shelves, lamps, baby strollers, shoes, booties, lots of clothes, papers, books, records. Entire lives buried in the mud. Pedro, the man who called 112 to try to save his disabled neighbor without success, starts to cry when he thinks of what has been lost. He had prepared a small trousseau for when his son, who is now 26 years old, left home. “They were things in there that we loved very much, like some towels that Grandma had embroidered, but now there is nothing left.”

They are all on edge, recovering from the trauma while working around the clock. They cry and laugh and are grateful for any help they receive. The national, regional and local emergency services, using the resources and personnel they have, have set priorities: searching for missing people, clearing major roads to ensure access to every location, pumping out water from basements and garages and places that are still flooded, removing wrecked cars, clearing the mud. While they do all these things, they are also helping the loca residents as much as they can, and the latter greet them almost with hugs.

Catarroja has been divided into six sectors for the emergency. The command point is located at the Jaume I school. The following people meet there every day at 8.30 a.m. and 6.30 p.m.: the mayor, the local chief of security, the director of the emergency operation (who is a firefighter), the representative of the firefighters in charge of each sector, and a military member of the UME. Because Level 3 (denoting a national emergency) has not been declared, the direction of the operation is in the hands of the regional government, not Spain’s central one. So the people in charge at these meetings are the firefighters.

“In each sector, a survey is carried out,” explains Mayor Silvent. “Then, access routes are cleared and we move forward little by little through the streets as if it were all a spider web. We pool all the needs to try to sort out the chaos. And each sector has a tent set up to answer questions from neighbors and volunteers.” Among the volunteers who are helping out on Blasco Ibáñez Avenue, some have been told where to go at these points. Other volunteers say that they tried phoning, did not get a municipal response and simply went to help on the first street they found with problems.

There are about 8,000 soldiers on the ground. There are also 2,450 firefighters from all over the country, as well as 9,700 National Police and Civil Guard officers and 130 Local Police officers (in the case of Catarroja, 32 of them). But they are not enough. They have barely done any work on Blasco Ibáñez Avenue. There are a few firefighters bailing out the water from the garage where four people died, and little else. Some Civil Guard officers on leave are helping out a volunteer with a tractor to remove cars from the street. The UME soldiers insist that priorities must be set in order to advance in an orderly manner, and that they will reach all the houses and all the streets.

3-AN UNPRECEDENTED WAVE OF SOLIDARITY: “Farmers and youths have saved us”

Meanwhile, the residents are constantly cleaning up and organizing supplies of food, cleaning products and water. They are helped by an army of volunteers who have come from all over the country, equipped with shovels and brooms, but also with tractors, trucks and excavators.

This wave of solidarity is probably the most moving thing that has happened since this devastating flood. On the street, everyone is constantly asking reporters to write about it: “Please, say it, a thousand times,” says Pedro Díaz. “We have felt alone and abandoned by the institutions, at least on this street, and it has been 10 days now. If it weren’t for these people, for the volunteers, for all the selfless help they are giving us, I don’t know what would have become of us.” Pedro starts to cry when he remembers the strangers who showed up in his basement to help him clean it, and to offer him food and water. “It is one of the most beautiful things I have experienced, and it has been in the middle of this horror.”

“Farmers have saved us,” says Rosa Picó at one of the drop-off points on a nearby street. “They started showing up from day one to help remove mud, to remove cars. It has been incredible. And all those young people who walked for miles with their brooms... and then they tell you that young people never show any solidarity. And what about the people who have crossed the country with their trucks and their machinery, paying for their own fuel. I have never experienced anything like this in my life. I can’t stop feeling emotional about what has happened.”

Blasco Ibáñez Avenue is full of volunteers who don’t make a big deal of it. “We saw what was happening and we came to help, that’s all,” says one. “How can you not do anything about something like this?” They are people like Francisco Oliván, a farmer from Cariñena. Or José Miguel Redondo, from Argamasilla de Calatrava, in Ciudad Real, who came with his trailer with a container tub.

They get water, fresh food, and sanitary and cleaning products from one of the many collection and delivery points around the town. There were three near their street, and on Thursday one more opened on Blasco Ibáñez, inside the school at the end of the street, Colegio Larrodé, which caters to students from kindergarten to high school. The gym remained standing because it was located on higher ground, and school officials were contacted by local authorities to see if they could organize a help center there. From then on, everything has been self-managed by teachers, families with kids in the center, neighbors and volunteers. A group of women are attending to people’s needs outside, at school tables arranged as a counter:

— Do you have any mops?

— There are none left.

— Okay, and laundry soap?

- Yes we do have that.

— Well, give me some, please. And some persimmons and some oranges.

Everything is organized and classified as if it were a supermarket. On one side are the canned goods, on the other are the milk, biscuits, bleach, detergents, fresh fruit and vegetables, water… In the afternoons, many restaurants and schools bring them leftover hot food. And there are people from the neighborhood who cook every day for them. The center is open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., although in reality the volunteers work from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. evening because, like everywhere else, there are so many things to do. María Muñoz, a 47-year-old teacher at the school, explains that they are overflowing with diapers and baby clothes that they don’t need, because almost all the babies have left the neighborhood for areas that haven’t been flooded. There is also an excess of clothing in general, because only those who live on the ground floor have lost it. But there is a lack of rain boots. And in other places they need laundry detergent and dishwashing liquid.

Elderly people and people with mobility problems are always brought what they need by a neighbor or a volunteer. Some go down the street with a shopping cart and even a megaphone in hand offering things: “Pads, masks, gowns.”

The residents of Blasco Ibáñez Street are as grateful for the solidarity of the volunteers as they are angry with the politicians, with every last one of them. Certainly with the regional premier, Carlos Mazón, for his actions on the day of the floods, for the lack of foresight, of involvement, for that alert at 8 p.m.. But when they talk about the subsequent management, the anger goes further. All the people interviewed for this story said it is not up to them to analyze who was supposed to be in charge of managing the emergency, but everyone agreed that this is an emergency like no other in decades and that they have felt abandoned by the politicians.

“Then there are all these dangerous hoaxes circulating,” says Aitana, a Business Administration student. If the volunteers have been the bright side of this crisis, the dark side has been the hundreds of hoaxes making the rounds, such as the one that claimed there were hundreds of dead people inside the car park of the Bonaire shopping center, when none were found, which have only added confusion and concern to a dramatic situation.

4-THE FUTURE: A glimmer of hope in the middle of the horror

Nearly two weeks after the floods, the work that remains to be done is enormous. Even so, there are small rays of hope on Blasco Ibáñez Street. The first few days the junk piles were like mountains that disappeared at night and reappeared in the morning, like Sisyphus’ rock. Luckily the street is wide and the volunteers’ machines have been able to enter without any problem, which has not been the case in narrower streets in Paiporta or in Catarroja itself, which are still full of rubble. On Blasco Ibáñez they have been removed, as well as the totaled cars, and in a matter of days the scene has changed considerably.

There is no gas, but the electricity and water are back, although the latter took a while to reach a block down the street due to a leak in a pipe. The neighbors are making progress emptying and cleaning the basements and ground-floor premises. They take turns using water pressure machines that work wonders on the floors and remove the mud from everywhere. “Let everyone who can send more in,” says Sarai. Like many other young people, she is making requests on Instagram for specific help that is required. At this point she has stopped cleaning and is focused on looking at all the aid that can be applied for, while her mother continues removing mud.

Pili is also doing the math to see if she can reopen her hair salon. “I see a tough future ahead. Getting started is going to be very, very difficult, but we will put all the strength we have into it,” she says. “We need the institutions to help us in every way, to help us more, to stop feeling alone in the face of this tragedy and little by little to overcome the trauma that has lodged inside us.” María, a teacher at Larrodé school, hopes that the help distribution center can soon be relocated so they can focus on fixing up the school and for the students to be able to return. Right now, they are either at home or attending classes in other schools. “The kids need to get back to normal as soon as possible,” she says.

Nuria wants to return to her home, her refuge, which she has to set up entirely again. But she believes that nothing will ever be the same. Vicente and Laura do not think beyond tomorrow or the day after. “It sounds like a cliché, but that’s the way it is”, says Vicente. “We are thinking only about the next day. We do not have a car and thank goodness my wife can work from home. What I do believe is that these villages have died. A couple of generations will have to pass before people forget this and families are willing to live here again. Although I don’t know. The truth is that seeing all the young people who have come to help, I think that with them, there is a future.” Pedro wants politicians, and certainly those of the Valencian government, to accept their responsibilities for the mistakes that were made and for the helplessness he has felt.

After several days on the street with them, Sarai’s mother, María Asencio, calls the photographer and me from afar and runs over to tell us the news.

— I wanted to tell you, before you go, that we have finally decided to reopen the shop. We don’t know how, but we will do so in March or April, even if it’s just a few items, for the summer season.

Today she is speaking, for the first time, with a smile on her face. The effects of this flood will take a long time to go away. There are those who have not yet found their missing relatives or buried their dead, who have lost everything, who live in tiny streets still filled with mountains of mud and trash and where your boots still sink in mud and you can barely walk. But many are looking for something to hold on to in the midst of the horror. “Please come back when we reopen the shop,” Maria asks before saying goodbye.

Credits:

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition