The election will be televised: 70 years of TV ads for US voters

Antoni Muntadas and Marshall Reese’s video art project shows how, from Eisenhower to Harris vs. Trump, presidential races run on propaganda

Political Advertisements 1952-2024 is a fascinating political video art project for which the seed was planted four decades ago. The year was 1984, when Republican Ronald Reagan defeated Walter Mondale to win re-election and the Spanish-born, United States-based post-conceptual artist Antoni Muntadas (Barcelona, 1942) began to collaborate with U.S. creative Marshall Reese (Washington D.C., 1955) on an investigation of television spots paid for by the Democratic and Republican Parties, beginning from when the first such TV ads appeared in 1952. Their birth coincided with the Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower’s winning campaign, powered by his famous slogan, “I Like Ike.” Eisenhower occupied the White House for eight years, a period characterized by McCarthyism, which brought with it political witch hunts and anti-communist obsession. The birth of televised electioneering in 1952 was only to evolve every four years, its most recent form taking shape during Kamala Harris’s current electoral battle against Donald Trump.

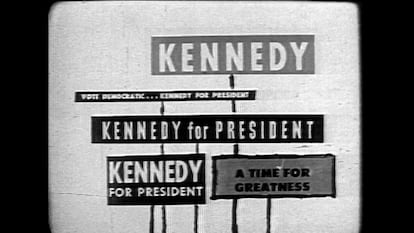

Muntadas and Reese’s film travels through 70 years of electoral TV propaganda, offering a unique perspective on the political history of the United States from an unusual angle that results in an extraordinarily truthful portrayal. All the candidates are here, many of their names linked to historic eras: Kennedy, Nixon, Reagan, Carter, Bush, Clinton, Biden, Obama. Viewing the project in this precise moment is somewhat discomfiting, given the agonizing uncertainty in which the country currently exists. In coordination with the debut of the latest version of their work, the two artists have published a short volume of conversations regarding the project titled Read My Lips, a slogan that was used by George H. W. Bush during the 1988 Republican National Convention to announce that he would not raise taxes if elected.

The cinematic collage is one of multiple readings, with one major theme being the importance of reading between the lines. The absence of any narration confers upon the strictly chronological montage an elevated sense of objectivity. Images and words serve to articulate a highly valuable testimony as to the evolution of the political imagination of a profoundly divided country. The film’s current version has been screened in Turin, Washington D.C., New York, and Minneapolis, and in the days leaded up to the election, it will be shown in Pittsburgh, with appearances in São Paulo and Lisbon on the eve of the election itself.

The prologue to Read My Lips provides viewers with chilling statistics that put electoral dependence on campaign financing into harsh relief. In 2024, election season TV advertising spending rose above $12 billion, 30% more than in 2020 and triple that of 2016. It’s interesting that Muntadas and Reese eschewed a focus on social media ads in order to continue exploring television, where message and medium converge. Their story sheds light on the political history of the United States in relation to collective imaginary, while at the same time, evidencing the absolute control exercised by the world of finance and corporate culture over the country’s reality. As Norman Mailer pointed out when he published his pamphlet Why Are We at War?, in connection to the 1991 invasion of Iraq, democracy in the United States is in grave danger of extinction, a statement that, today, has taken on new relevance.

The emotional texture of Political Advertisements is complex. It does contain moving scenes, as when Jackie Kennedy sought votes in Spanish for her husband in 1960, three years before he was assassinated in Dallas. Other moments come across as comic, but the common denominator of the film, as seen through today’s eyes, is fear, frequently run through with hate. One repeating trope of U.S. electoral seasons is the ominous tone employed when voters are warned that they are facing the most important political decision of their lives. That idea seems even more relevant today, but the tragic and dangerous moments of the past illustrated by the ads are neither few nor insignificant, like the image of a mother carrying her naked daughter in her arms, the child’s skin bearing the catastrophic markings of napalm. In one of the most effective and shocking ads, aired in 1964 as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s election campaign, a little girl reminiscent of Shirley Temple innocently plucks a daisy and endearingly mixes up the numbers of a countdown that eventually turns sinister, culminating in a nuclear explosion.

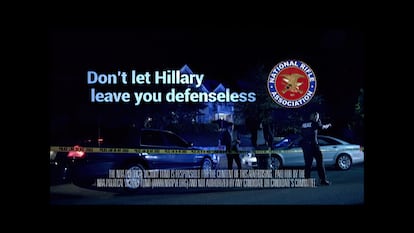

In their attacks on the opposition, the election ads explicitly and implicitly reference domestic strife in the forms of racism, widespread poverty, immigration, taxes, and healthcare. Geopolitical consequences stemming from the country’s economic and military arrogance are evident in their references to Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan (although it does not appear in the film, it is difficult not to reflect on the United States’ role in the current conflict in Gaza while watching Political Advertisements.) By compiling images from almost three quarters of a century of the history of the most powerful country on the planet, Muntadas and Reese tell a story that underlines the defenseless of U.S. citizens in the hands of a system that deprives them of all agency, handing it over instead to corporations. That message is not explicit — to state it outright would go against the premise on which the film is based. It falls to the viewer to connect the dots, a range of possibilities that have never been more terrifying. Stakes are high and it’s hard not to squirm in one’s seat when, at the end of the chilling ride, you see Harris’s smile or Trump’s ranting and raving, his inordinately long red tie flapping in the wind.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.