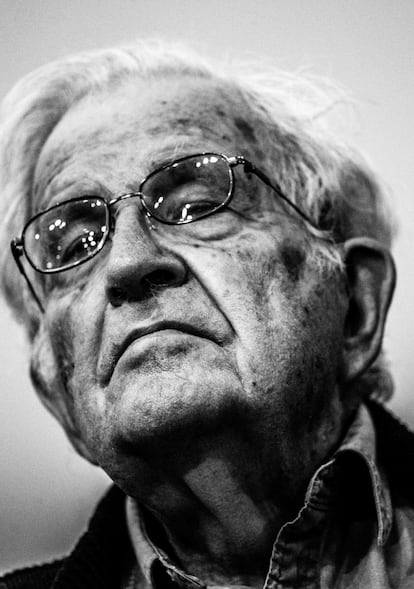

Noam Chomsky: ‘American democracy is in very serious danger’

In this highly personal interview, the 93-year-old intellectual talks to EL PAÍS about his childhood, his views on Trump and Biden and why he considers himself a pragmatic thinker

At 93 years of age, Noam Chomsky still writes, gives lectures and interviews, and stands out front for what he believes is right. He is part of the European progressive movement Diem25, and has raised alarms about the risks of climate change while becoming the scourge of Trumpism. He is also the father of modern linguistics, having established the theory of generative grammar in the 1950s. A prolific author, renowned philosopher and incorrigible activist, he was arrested for opposing the Vietnam War, blacklisted by Richard Nixon and supported the publication of the Pentagon Papers. More recently, he urged Americans to vote for Joe Biden in the 2020 elections. Since 2017, he has lived in Tucson, Arizona, and spoke to EL PAÍS by video call from his home. The professor’s gray hair appeared on the screen at the precise time, and while the years have weakened his voice, his thoughts remain as sharp as ever.

Question. I read that you wrote your first essay when you were only 10 years old, and it was about the Spanish Civil War. Is that correct?

Answer. Yes, and I can date it exactly, because I know what it was about. It was about the fall of Barcelona. So it was February, 1939. Sure, it was not a great article, but it was an article about the spread of fascism in Europe, from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Barcelona. From my 10-year-old point of view, it looked as if the world was coming to an end, as if fascism was uncontrollable.

Q. I read that when you were a child, you began working at a kiosk with an uncle, selling newspapers. Or that you helped him, at least. I would like to know, how did that mark you, how did that influence you?

A. There is a good deal of irony, tragic irony, in that question. I grew up in the Depression. I was a child in the early 1930s. My family were immigrants, mostly unemployed, with really bitter suffering from the Depression, but there was an atmosphere of hope, aspiration and expectation, because of the labor movement. The labor movement was reviving. It had been crushed by force during the 1920s, but it was reviving. There were militant labor actions, there were political parties, radical political parties. There was debate, discussion, cultural activities. There was a sense of: “We can all get out of this together.” In fact, if you look at what happened in the 1930s, the effect in Europe was fascism, Franco, Mussolini, Hitler, other minor figures. That was Europe. The reaction to the Depression in the United States was social democracy. The New Deal, Roosevelt’s New Deal, pressed by labor activism, popular pressure, led to the modern era of social democracy, picked up by Europe after the Second World War. Now that was 90 years ago. Look at today, there are other crises today, very serious ones. Europe is holding on to some form of social democracy. The United States is leading the way to proto-fascism, the reverse of what happened in my childhood.

Q. What about the pandemic? You mentioned the Great Depression, and the effect that had on the US and Europe, but can the pandemic play a similar role in the sense of “We can do this together?”

A. It should. And there are some signs of it. So when you get to the local level, you do find people cooperating with one another, helping each other. In many poor places around much of the world, local groups have just gotten together to help people in need, sometimes in remarkable ways. The favelas in Brazil are among the most miserable slums in the world. I’ve seen them. They’re run by biker gangs, drug cartels. The police are also extremely violent. Well, what’s happened during the pandemic is that the gangs, the criminal gangs that have been terrorizing the favelas have been organizing people to deal with the crisis. In the favelas, plenty of people don’t even have water. They’re working to help people at least have access to water, to have access to vaccines, to help each other in need. If there’s somebody, an old man stuck in an apartment who can’t get food, they bring him food, things like that are happening on the ground. Now, go to the leadership level. What are they doing? They’re monopolizing vaccines for themselves. They are demanding that the huge pharmaceutical corporations, which are super rich, should maintain control of the exorbitant patent rights that were given to them by the neoliberal regime, a regime which is radically opposed to free trade.

The Republican Party is no longer a political party. It’s a neofascist party

Q. Not only in the US, but also in Europe, why are the far right winning votes?

A. They have taken over. I mean, they always dominate the system, of course, in Spain as well. But in the last 40 years, they’ve had an overwhelming triumph in gaining power and wealth. Just take a look at some of the numbers. In the United States, the Rand Corporation, a very respected quasi-governmental corporation, did a study of the transfer of wealth from the working class and the middle class. Their estimate is $50 trillion, $50 trillion stolen from the working class and the middle class, and put into the pockets of the super rich, and the people that run and own the corporate sector. That’s pretty substantial. And that’s an underestimate. Reagan opened the door to tax havens, for example, lots of other ways to rob the public. There has been a major period of massive class war, and they have gained enormous power. It’s been very destructive to the population of working people in the United States. Male workers, for their wages, are actually, in real terms, about where they were in 1979. A lot of wealth has been accumulated, but it’s gone into very few pockets. Europe had its own form of this. The austerity programs in Europe badly damaged working people and the poor, and enriched the very rich, not as extreme as the United States, but it happened. It’s led to anger, resentment, what’s called populism, which is very different from traditional populism, but a sense that, “The world’s going wrong, we don’t like it.” This is fertile terrain for demagogues of the Trump/Orban variety, and they’re capitalizing on it.

Q. One year on from the assault on the US Capitol, what are the consequences?

A. The assault on the Capitol was an effort to overthrow an elected government. Very explicitly, their claim was coming from Trump that the election was stolen, so let’s march on the Capitol and save our country from the stolen election. Well, an effort to overthrow an elected government is what’s called a coup. It almost succeeded. It’s now been reported extensively. We have videotapes, we have details. A few people, Republicans, in fact, refused to go along, and prevented the coup from succeeding. But it has been followed by a soft coup, which is taking place before our eyes. You read about it every day. The Republicans are planning carefully to ensure that next time, their coup will succeed. They’re doing it very systematically, perfectly in the open, at the state level where elections take place, trying to ensure that the people who run the elections physically are there when you cast your vote, the election monitors make sure that they are right-wing Republicans, who will ensure that if people vote the wrong way, the vote won’t be counted. The Republican Party is no longer a political party. It’s a neofascist party. The United States is a technologically advanced society, and culturally advanced, in some sectors, but culturally pre-modern in other sectors. That’s Trump’s voters, and he’s a very effective demagogue. He has succeeded in tapping the poisons that run right under the surface in American society, bringing them to the surface, mobilizing them. They are now a group who worship Il Duce, the leader chosen by God. He’s got them in his control. Those are the ones who stormed the Capitol, and are now planning to ensure that next time it’ll work. American democracy is in very serious danger.

Q. Has the Biden administration been more progressive than you expected?

A. Well, I didn’t expect much, frankly, but the domestic programs have been better than I expected. Actually, to a large extent, they were designed by Bernie Sanders, representing the more progressive wing of the base of the Democratic Party. He has an important position as a director in the department of the budget that sets up the programs. The major Biden program [Build Back Better], the one that’s being thought about right now, was initiated by Sanders. In social welfare, the United States is a laggard, way behind other countries. Take such simple things as maternity leave. There are about six countries that don’t have it, the United States, and a couple of Pacific islands. Everybody else has it. The United States? Can’t have it. Republicans? 100% opposed. The Democrats like [Senator Joe] Manchin have blocked it. That’s the richest, most powerful country in the world, but efforts to try to develop simple social democratic measures are blocked by private capital, and by the neoliberal ideology, which is radically opposed to them.

The assault on the Capitol has been followed by a soft coup, which is taking place before our eyes

Q. Do you still consider yourself an anarchist, and what does that mean?

A. Like virtually every term of political discourse, the term “anarchism” is used in widely different ways. The same is true of liberal, conservative, socialist, Marxist, they mean all sorts of things. In the case of anarchism, the idea is that any form of hierarchy, domination, authority, whatever it may be, in any aspect of life, from the family, to international affairs, any such relationship has to justify itself. It’s not self-justifying. So if a community, decides democratically that they want to have traffic rules, drive on the right side of the road, stop at a red light, I think they’re subjecting themselves to authority. But I think you can argue that it’s legitimate authority. On the other hand, very few relationships withstand this critique. And the task of an anarchist is first of all, to discover them, which is not a small task, reveal them, to bring people to contemplate and deliberate about them, and then, to change them, if they find them legitimate. Even that first step, discovery, is not easy, right at the present time. So if you had asked my grandmother whether she was oppressed, she wouldn’t even know what you’re talking about. She was living the way a woman was supposed to live, taking care of the house, taking care of the children, doing what her husband tells her. That’s not oppression, that’s just life. Well, to discover that that’s a form of oppression takes work and effort.

Q. What about work?

A. What’s a job? A job, for most people, is spending most of your waking hours following orders from a master, who is a totalitarian master. They can give orders of a kind that Stalin couldn’t have dreamt of. Stalin couldn’t have told people that you’re allowed to take a five-minute bathroom break or that you’re not allowed to talk to that person next to you. And maybe your master is kind enough to allow you the leeway, but it’s the master’s decision. That’s called getting a job. Today, most people think that’s the norm. They react like my grandmother did, and would, if you’d asked her if she was oppressed. That wasn’t always true. To go back to the early Industrial Revolution of working people, bitterly opposed this form of autocracy, which was taking away their dignity, their rights and keeps reviving today. Plenty of people are saying the same thing. In fact, many of the people who are just refusing to go back to work, the so-called Great Resignation, are saying it in their own way.

Q. Is it possible to have an organized economy without some kind of authority?

A. Sure. In fact, Spain gave us very good examples of it. Take a look at the Mondragon collective conglomerate. It’s been around since the 1950s, worker-owned, largely worker-managed. You can find flaws, if you look, but to a large extent, in fact, to an unusual extent in the world, it’s a substantial, successful, long-standing conglomerate that is based on the idea that the participants in a community should control it.

Q. You also talk about consent, how people consent to authority and are willing to accept authority, sometimes, no matter if it’s not legitimate or justified.

A. Human nature covers the range of options available to humans. If you read classical liberals, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and others, their conception was that the essence of human nature is freedom from arbitrary constraint. They didn’t live up to it, by any means, but we’re talking about the thinking of, say, John Stuart Mill, leading classical liberal thinker in England, that his view was that in an enterprise, the working people in the enterprise should own and run it. That was classical liberalism. Of course, all of this was crushed by capitalism, which took a different course of authority, domination, subordination to a master. And in its extreme savage form, the kind of neoliberalism that’s been imposed in the last 40 years or so, with devastating effects almost everywhere.

Q. Do you consider yourself a pragmatic thinker?

A. We should do what we can do, not seek to do what we can’t do. There’s no point in romantic gestures, which are going to not only fail, but lead to the worst outcomes. We have to face the world as it actually is, and act in ways which will improve it, overcome problems and lead to a better world. I had friends, back in the ‘60s, who decided they wanted to have a revolution. So they would go out to a factory, say, the General Electric factory, and hand out Mao’s Little Red Book at the gates of the factory, to organize the working class for a revolution. Well, you can imagine what happened. That’s not the way we bring about change. What they did is strengthen support for reaction, and support for the war. You have to face the world as it is, not the way you would like it to be. You try to create the world that you would like, but by facing the world as it is.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.