‘Every candidate has their flaws’: How Super Tuesday went down in the heart of Virginia, a key swing state

Voters in The Plains, in the center of the state, said they were unenthusiastic about supporting either Joe Biden or Donald Trump

In the almost inevitable battle between Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden for the White House, places like The Plains, in Virginia’s Fauquier County, are on the front-line. Swing constituencies in swing states. These are the places that will tilt the final result of the November presidential election to one side or the other. And where, on Super Tuesday, only one thing was clear: although Biden and Trump won the primary decisively, neither of them have completely convinced voters.

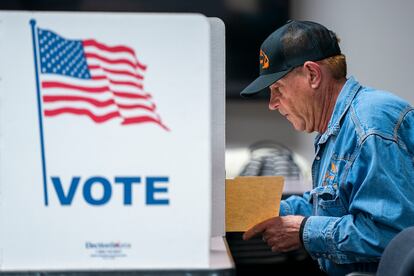

“People aren’t very motivated… every candidate has their flaws,” admitted Susan, a Republican volunteer handing out leaflets at the entrance to Coleman Elementary School, in a rural area outside The Plains where locals advertise horse feed and agrotourism initiatives. Turnout on Tuesday “is less this time than four years ago,” the retiree added.

The peculiar system of U.S. presidential elections means that in most states, the winner takes all the electors at stake, regardless of whether the candidate won by a single vote or with an overwhelming lead. This means that, although in theory all votes are equal, in practice some are more equal than others. Voting Republican in a state with a large Democratic majority like California, or voting Democratic in a Republican state like Texas, is a laudable democratic gesture, but it does not serve to tip the balance. The race is only hotly contested in a handful of states, where there is a very even balance. In these swing states — such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia, Nevada and Arizona — every vote counts. And both parties scramble for each and every one.

Virginia is one of those swing states. Traditionally a Republican bastion, in the last two decades it has been leaning towards the Democrats in the presidential elections, supporting the party in every one since 2008. Broadly speaking, the urban north of Virginia, where the federal government and the defense industry are the main economic drivers, votes for the Democrats, while the rural south votes for the Republicans. These two realities come face-to-face in Fauquier, a lifelong Republican county, where the party has been losing its grip. On Super Tuesday, there were only a trickle of voters in the county.

Among those who agreed to reveal how they voted, there was a near even split between Trump and Biden supporters. Few said they were excited about the choices, a reflection of the surveys showing that 70% of American voters do not want another showdown between Biden and Trump this November. Some said that after voting for the Republican in 2016, they had voted for the Democrat in 2020, and were now going back to Trump. Another voter admitted that, after years of voting red, he was now blue “to death.”

“I voted for Trump, and I’m going to do it again in November,” said Sheila, a retired woman, after leaving the polling station. “When he was president he did what he said he would do, close the border, make energy prices reasonable. I don’t like going shopping anymore, every time I go the prices have gone up.” She also admitted that, although Trump “loves this country, and he loves us,” he “does not have the best personality in the world.”

Giselle Mancioni, a former real estate agent, was also leaning towards the former president. “He is the strongest candidate in the race,” she said, adding that she hopes Trump will solve what she thinks are America’s main problems: the economy — a widespread complaint among Republicans, even though the economy grew 3.2% and unemployment has fallen to 3.5% — and crime. But her enthusiasm ended there. Almost immediately, considering the 91 charges Trump faces in four separate cases, she acknowledged that “honestly, I would prefer the Republican candidate to be someone else, but at this point he is the clear winner, so I am not going to change my mind.”

Democratic voters in Fauquier County, by contrast, had a very different list of priorities ahead of November’s election. This group said their main reason for supporting Biden was due to the need to defend the democratic system and freedoms.

“Democracy is in danger. And if we, the people, do not manage to get it out of this hole, this country will no longer be the country of the people. It will not be the same country, nor will it be the same world we are living in. My fear is that if the other candidate wins, we will never have elections again. Not like these, open. I fear he will turn this country into his playground,” said Gail Rainbow. “That’s why Biden is my candidate,” added the former Republican voter who is still registered with the party. Rainbow, however, admitted that the president’s age, and his lapses in public, “are a concern.”

Another Biden voter, who did not want their name printed, was also not particularly passionate about their choice. “I like his government,” they said. “I am voting for him, mainly, because I don’t like the Republican candidate. I come from a lifelong Republican family, I’ve always voted Republican... but now I can’t vote Republican. The Republican Party has shut me out.”

One name at the Coleman Elementary School voting center was conspicuously absent: Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina and Trump’s only rival in the Republican primary contest. On Super Tuesday, she was once again widely defeated by Trump, only managing to win in the state of Vermont. Only one person who spoke to EL PAÍS, a woman who was running to her car, said she had voted for Haley. “In November, I will vote for Biden. But today, I voted for Haley,” she said. When asked why, she responded: “Because I wanted to poke Trump in the eye.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.