The ‘siege’ of Minneapolis: How residents of the Democratic city are resisting Trump’s immigration crackdown

With a mix of solidarity and defiance, Minnesotans have spent weeks refining the network they use to confront federal agents — and have managed to push back against the US government

For weeks now, phones haven’t stopped buzzing in Minneapolis. They vibrate hundreds of times a day — one jolt for every message received by residents enrolled in the Signal groups that monitor the 3,000 secret immigration police agents deployed by Donald Trump in the city.

On this encrypted platform, everyone’s role is defined by an emoji code: cars, plates, bandaged hearts… Some patrol the streets looking for the masked federal agents, who drive unmarked cars and are armed to the teeth. Others provide first aid when things go wrong, photograph license plates, or cross‑check them against available databases.

There are several check‑in calls each day. When someone reports a raid in progress, the vehicles of the “observers” in the area race over to try to stop it or, at the very least, to witness it or disrupt the hunt for immigrants. Once there, they blow whistles, film the agents with their phones, and confront them. Sometimes they end up getting arrested.

Each neighborhood in the Twin Cities (the metropolitan area formed by Minneapolis and St. Paul, with a combined population of 3.7 million) has its own group. And getting in isn’t easy. The reason becomes clear with the first warning given to newcomers: it’s best not to share any personal information, because “the far right has infiltrated” the groups. The FBI has also warned that it will be reviewing their content.

This is the state of affairs in the new normal of occupied Minneapolis, which has spent the past two months resisting Operation Metro Surge, ordered by the federal government to speed up deportations in Minnesota, a Democratic state.

The fact that the percentage of undocumented immigrants is lower than in many other parts of the country didn’t stop Trump from warning residents on January 13 that their “DAY OF RECKONING AND REVENGE” had arrived. It wasn’t clear at the time what exactly he meant, but this week there was no doubt that the resistance of that “great people” is derailing the White House’s plans.

“The largest deportation in history”

Minneapolis is the seventh stop — after Los Angeles, Washington, Chicago, Portland, Memphis, and New Orleans — on Trump’s authoritarian march forward, eager to sign off on the “largest deportation in U.S. history” and cross names off his enemies list.

In all those cities, federal agents and the National Guard ran into obstacles, but what’s happening in Minnesota looks more like an impenetrable wall, especially since Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and Border Patrol officers shot and killed two unarmed Americans: Alex Pretti, an intensive‑care nurse at a veterans’ hospital, and the poet Renée Good.

Far from intimidating protesters, those deaths — captured on the phones of bystanders like Kayla Schultz, who witnessed Pretti’s killing without flinching — have fueled activism among thousands of residents, from longtime organizers to people who, as Joey Keillor told EL PAÍS, had never demonstrated before.

“They’ve run into the toughest people in the country,” warns Jaylani Hussein, leader of the Somali community that Trump has used as a pretext for the occupation, blaming it collectively for massive fraud in public assistance programs. “We survive the harshest winters, and we do it knowing we can rely on our neighbors. We’ve cerated the resistance manual for the cities that come after us on the list.”

That manual is built on solidarity, and it can’t be understood without the precedent of the protests that erupted after the killing of George Floyd, an African American man, at the hands of a white police officer — nor without the networks and infrastructure forged in the Twin Cities during that time. Although this time is different. “What’s happening now is unprecedented,” says Jim Winterer, a retired journalist. He has lived his entire life in Minnesota and was one of the few who raised his hand when, at a demonstration last week, the speaker asked whether anyone in the crowd had taken part in the protests against the Vietnam War.

Columnist Lydia Polgreen, who has covered conflicts around the world, wrote in The New York Times that what she saw on the ground in Minnesota — a state that didn’t vote Republican even during Ronald Reagan’s 1980 landslide — reminded her of the beginnings of a civil war. Locals here prefer a different comparison: the revolution against the British that brought about U.S. independence 250 years ago. “This time the king’s name is Trump,” said Ken Brown as he protested, holding a sign he designed himself accusing ICE agents of being the president’s “orcs.”

Brown recalled — like dozens of other people interviewed in recent days — the moment he felt the “need to do something.” In his case, it came early, when he began seeing masked agents patrolling his city. But it could just as well have been after witnessing the brutal arrests documented by the Signal observers, or the live broadcast of the deaths of Pretti and Good, two white Americans, like the vast majority of those protesting.

Bridge over the highway

That “something” can be as simple as standing for hours in the cold holding signs calling for ICE to be expelled or abolished on the overpasses, so drivers honk as they go by. The tenants of a building at the corner of 28th Street and Thomas Avenue have been coming out every Wednesday afternoon for weeks to blow their whistles as hard as they can. Some neighbors donate or distribute food to families in need, or to those too afraid to leave their homes for fear of being arrested and deported. Others hand out donuts, goggles and gas masks, lip balm for the cold, and hand and foot warmers in a city that this week hit -4ºF.

Sometimes, helping is as simple as buying something: Miguel Zagal, from Taquería La Hacienda, said last Wednesday that his parents’ business stayed closed for three weeks out of fear, and when they finally reopened, the neighborhood rallied around them so strongly that they ran out of food before closing time every day. Other times, the strategy is not spending: many in the city have joined a boycott of Target, one of the 15 Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Minneapolis. The reason? The speed with which its executives bowed to White House demands and eliminated diversity, equity, and inclusion programs that had been adopted as a calculated business after Floyd’s death.

Sarah Charging, a Native American member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of North Dakota, began protesting after the death of Good, who was shot three times at point-blank range by an ICE agent named Jonathan Ross, who has yet to be charged. Since then, Charging has stood “four or five times” a week, “before or after work,” in front of the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, the brutalist monstrosity where detainees are taken. These detainees include undocumented immigrants, who are sent to other states to hinder their defense, as well as U.S. citizens arrested at protests, and refugees detained by mistake, who are then not reimbursed for the travel costs of returning from places like Florida or Texas.

Next to a sign welcoming visitors to the complex — where someone has crossed out the word “employees” and written “pigs” — a car marked “Haven” keeps watch 24 hours a day to assist those released without charges, often in the middle of the night. “They confiscate their phones and take their coats,” warns Cathy Anderson, one of the volunteers.

At the Whipple, it’s not unusual for the air to smell of tear gas, and at all hours there are people — megaphone or not — shouting at and insulting the uniformed officers guarding the entrance or the tinted‑window SUVs driving into the compound, around which a fence has been erected to contain the protesters. Sometimes the agents charge or fire smoke canisters. Around 10 a.m. on Friday, one of them rushed toward the group gathered there, dragged a man across the ground, and arrested him for no apparent reason.

Frog costume

These days, the Whipple is dotted with upside‑down U.S. flags — an old maritime distress signal that here reflects a country in crisis — and a woman dressed in a frog costume, who described her protest strategy as an act of “tactical frivolity.” Mike Camilleri, a teacher from Denver, Colorado and father of three, said he had driven 13 hours to “take notes” so he could tell his neighbors how “the free people of Minnesota” defended themselves. A retiree named Lesley Ernst wore a whistle around her neck and held a sign reading “Jesus loves you.” “I suppose I’m one of those violent agitators Trump talks about,” she said wryly.

Trump often claims — without evidence — that all of this is funnded by “destabilizing” actors such as progressive billionaire George Soros. Julie Prokes’s contribution, however, seems far more modest. A state employee, she took the week off to set up a table in the Whipple parking lot, offering protesters everything from energy bars to hot coffee to whistles she says she prints at home on a 3‑D printer “at a rate of 50 a day.” “I pay for everything out of my own pocket,” she said. She also offers her car, running at all hours with the heater on, in case anyone needs to warm up.

Beyond that improvised stand, whistles are handed out for free at many spots around Minneapolis: from Birchbark Books, the bookstore owned by Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Erdrich, to the bakery across from the place where, two Saturdays ago, Border Patrol agents shot Pretti in the back. There, as at the site where Good lost her life, hundreds of people pass by each day to mourn in silence, pay their respects, share their thoughts aloud, light a candle, or leave a handwritten note.

In all these scenes, white men and women are the majority. Not only because they make up 77% of Minnesota’s population, a state undergoing demographic change, but also because thousands of people — especially Hispanic and Asian families — have not left their homes for weeks out of fear of being arrested. It’s not only undocumented immigrants; it’s also citizens and legal residents in a city where it’s become risky to go about your life without a passport.

That nightmarish atmosphere keeps many Latinos from joining the protests or taking part in the groups tracking ICE’s movements. Among those who do dare is Rogelio Aguilar, who attended the massive demonstration that filled those Minneapolis streets on Friday, accompanied by an improvised Bruce Springsteen anthem shortly after the rock legend performed a surprise set at a local venue. Aguilar wore a Mexican flag and poncho, and said he has been taking long walks around the city dressed that way because, he added, “Chicanos are always the ones who step forward.”

He has become modestly known on these streets, and says he does it for the people who can’t protest. People like Clara and Manuel, for example, who agreed to speak with EL PAÍS in the modest south Minneapolis apartment where they have been holed up for two months.

They are undocumented; that’s why Clara and Manuel are pseudonyms. They barely work, so they survive on the solidarity of neighbors who, they say, are “pure güeros.” “Discovering that they were there for us has been the positive part of all this,” she explains, though she sometimes loses hope that things will “go back to how they were” and that they will be able to shake off “the fear.”

Their eldest son, who is a U.S. citizen, does the grocery shopping and takes the younger children to school, where they hear stories about what is happening — stories that force their parents into conversations they never imagined having at such a young age.

In the city, the memory of Liam Conejo Ramos remains painfully fresh — the five‑year‑old boy ICE used as bait to try to arrest his mother. When he was detained, he was wearing an oversized hat and a Spider‑Man backpack that was taken from him at the Texas detention center where he awaited deportation alongside his father, before a federal judge ordered both of them released on Saturday. The image became a symbol of the brutality of Trump’s operation. But it has not slowed the crackdown: two other children from his school were arrested last week.

A neighbor of Clara and Manuel, also Hispanic, explained that even though she does have papers, she is afraid “even to go to the corner to take out the trash,” and that when she has a doctor’s appointment she uses an app to request a volunteer driver. “If the person behind the wheel is white,” she says, “then you feel safer.”

Last Monday, Trump removed Greg Bovino from the head of the operation on Monday, replacing him with the so‑called border czar Tom Homan, and has spoken of “de‑escalation” in an effort to contain a growing image crisis after the deaths of two U.S. citizens and mounting evidence contradicting claims that his immigration police are only targeting “the worst of the worst.”

The New York Times reported that the acting head of ICE, Todd Lyons — whom a judge reprimanded two days earlier for obstructing justice — sent a memo to his agents on Wednesday authorizing them to conduct home searches without a warrant, despite the fact that the law prohibits it.

Arrests of U.S. citizens have also intensified. A group of them, now known as the “Minnesota 16,” gained unwanted notoriety when Attorney General Pam Bondi posted their photos and personal information on X, disregarding the presumption of innocence and the fact that she was effectively placing a digital target on their backs.

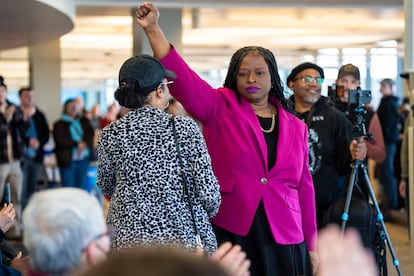

On Friday, two journalists were arrested. The day before, Nekima Levy Armstrong recounted her own ordeal to EL PAÍS. Armstrong had been detained for taking part in a protest at a church in St. Paul whose pastor has ties to ICE. The White House later circulated a photo of her that had been altered with artificial intelligence. “They showed me crying, hysterical, when I didn’t shed a single tear,” recalled Armstrong, a lawyer by profession, whose case made headlines around the world as yet another example of the Trump administration’s lack of scruples. “They also exaggerated my features and darkened my skin. There’s only one word for that: racism.”

The activist says they put her in shackles “as if I were a murderer,” that she still hasn’t gotten her phone back, and that the agents took photos with her and the two other people arrested in the same incident as if posing with a trophy.

“They can do all that, but they won’t silence us. They won’t intimidate us. We’ll keep facing their weapons with our whistles.” Armstrong delivered that warning halfway through the conversation. Interrupted repeatedly by the constant buzzing of her phone, she ended with the same plea to an outsider that everyone in Minneapolis’s new normal seems to offer: “Be careful and stay safe.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.