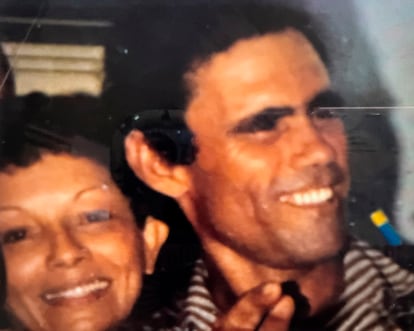

Isidro Pérez, the elderly Cuban fisherman who died in ICE custody after nearly 60 years in the US

The 75-year-old man, who spent his days in a Miami park and had a fragile heart, was detained by immigration agents on June 5 and died on June 26 from causes still under investigation

Isidro Pérez liked fishing and made a living, while he was still healthy, repairing boats. At 75 years old, with nearly six decades in the United States and after four heart attacks and three catheterizations, he lived on a boat anchored near a park in Key Largo, south of Miami, and spent his days sitting on a bench in a coastal park, his family says. It was there that the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested him. Last week, less than a month later, Pérez died in ICE custody from causes yet to be confirmed.

On June 5, ICE agents detained Pérez, and the following day he was transferred to the Krome Detention Center in southwest Miami. It is unclear where he spent the night of June 5. Monroe County police have no record of the arrest.

His ex-partner, 82-year-old María Adanéz, says she was driving on the Florida Turnpike, about an hour from her home, when her ex-son-in-law called to inform her that Pérez had been arrested. The next day, authorities called her asking about Pérez’s health. “I told them about his heart attacks and the three catheterizations he had undergone.” From Krome, “a young man named Lázaro” gave her a few minutes to talk to him. “He told me he was freezing because he was in a place called ‘the fridge’ and had asked for a painkiller,” Adanéz recalls.

He called her again five days later: “He said he was sleeping on the floor, that he had asked to be taken to the infirmary, but there were so many people that he had to wait.” On another occasion, he told her he hadn’t received the pills, and she insisted he ask for help. “After that, I didn’t hear anything from him,” she says.

According to an ICE statement, Pérez was hospitalized on June 17 and released on June 25. The next day, he complained of pain again and was transferred to Kendall Hospital, where he died.

Although there is no record of the June 5 arrest, ICE states that Pérez was charged with inadmissibility under the Immigration and Nationality Act. Pérez had a criminal record, having been convicted in 1984 for possession of marijuana with intent to distribute. According to court documents cited by the Miami Herald, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison and two years of probation.

Adanéz explains this was a case reopened after president Ronald Reagan took office. She met Pérez when she arrived from Nicaragua in 1979. In 1981, they moved to Key Largo and lived together for seven years, though they never married because she was a widow with several children. “It would have seemed ridiculous,” Adanéz says even now.

When Pérez was imprisoned for six months in Pensacola, in the far northwest of Florida, Adanéz would visit with her children and they would have breakfast together. She believes Pérez was partly convicted for going to Cuba during the Mariel exodus to pick up people. “He went to Mariel to pick up people, and that’s why they gave him six months, for bringing people, and they took his boat,” says Adanéz, who argues that Pérez never had legal trouble again and was well-loved in the neighborhood; people sought him out to repair their boats.

“We used to fish; he liked fishing. We had a license in my name because he didn’t want to deal with his immigration paperwork.” He liked going to Cuban markets, where they sold fruits and vegetables. There were never drugs, not even talk of drugs in the house, says Adanéz about the man who helped her raise her children.

But Pérez’s health declined over about 25 years, since his first heart attack. He also had two spinal surgeries, one on his foot, and suffered from osteoporosis. “He was shrinking because of his spine. Recently, he fell and broke his shoulder on a tree root, and still had a medical appointment pending,” says Adanéz, who assures that although they were no longer a couple, they always maintained a close relationship. “He used to call me three times a day.”

She brought him food, bought him a small stove and a battery-powered radio because there was no electricity on the boat. One of her sons brought him gas. “Since I saw he was declining, I always helped him,” says Adanéz, “so he wouldn’t be in need of anything on the boat.”

Pérez is the fifth person to die in ICE custody this year in Florida, where one of the largest anti-immigrant crackdowns in the country is underway, led by Republican Governor Ron DeSantis. The cause of death is under investigation, according to authorities.

Pro-immigrant and human rights groups have expressed concern about overcrowding in southern Florida ICE detention centers. Last week, Miami Congressman Carlos Giménez toured Krome as part of a congressional inspection visit and said the conditions were not deplorable or inhumane, though “it’s not the Ritz.” Giménez said most detainees arrived at Krome “because of some kind of an arrest, and then they were transferred over here.”

On the night of June 26, Adanéz fell asleep and missed a call from Krome at 10 p.m. She learned in the morning from Pérez’s daughter that he had died. Pérez had grandchildren, though he didn’t see them because “he didn’t go out anywhere, he spent time on the bench at the pier,” says Adanéz.

According to Adanéz, Pérez never thought he’d have more trouble with the law because “he never bothered anyone.” “He said that once you’ve been tried once, you can’t be tried twice. But now the laws seem to have changed,” she adds.

Adanéz does not want to make political comments because she comes from a country where she learned “to live under the gag law” and fears giving an opinion that might harm her family. She and her entire family are U.S. citizens but no longer even know if that means anything: “The laws are changing, and given what you hear, it’s better to keep quiet.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.