US stations 24,000 officers on southern border ahead of end of Title 42: ‘Don’t risk your life’

The streets around a church in El Paso have been cleared of the thousands of migrants who had set up camp there, while immigration officials have issued hundreds of “Alien IDs” with instructions to show up in court at a later date

Edixon, a 19-year-old Venezuelan, was “angry and stressed out” at about 10:30 a.m. Wednesday in downtown El Paso. He had just crossed the U.S.-Mexico border illegally at dawn from Ciudad Juárez, along with his girlfriend Milena, who laughed euphorically at the feeling of having made it. With her pants torn by the barbed wire, she protected herself from the sun as she sat on the ground in the shade of a portable public toilet.

Edixon and Milena are among the last migrants to have crossed while Title 42 remains in place. The regulation, part of a public health law dating back to the 1940s, was imposed in 2020 by former president Donald Trump with the excuse of protecting America against the spread of the Covid pandemic, and it allowed border officials to immediately turn away 2.6 million people without the usual administrative paperwork and without the right to seek asylum. That measure expires on Thursday, and the prospect has encouraged thousands of people to try to reach the border.

What will happen then is is at this point difficult to predict even for the homeland security secretary, Alejandro N. Mayorkas, who in a press conference admitted that “the next days and weeks could be very difficult.” He also recalled that the Biden Administration has reinforced personnel on the ground (more than 24,000 officers in total along the 1,951-mile (3,200-kilometer) border. Mayorkas had two messages for prospective migrants. One: “Our border is not open.” Two: “Do not risk your life and your life savings only to be removed from the United States if — if and when — you arrive here.”

Like so many others, Edixon and Milena ignored those warnings. They walked for three months and crossed Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico. Once at the border they continued a little further, to the Church of the Sacred Heart, in downtown El Paso. Edixon said he had “all his hopes placed in this shelter,” the epicenter of the latest migration crisis in the city, where in recent days more than 2,000 men, women and children were sleeping in the streets adjacent to the temple. By the time Edixon and Milena got there, only a few dozen remained. “I don’t know what we’re going to do. I don’t know if it’s a good idea to turn ourselves in. They are going to kick everyone out. They are going to break our hearts,” he said.

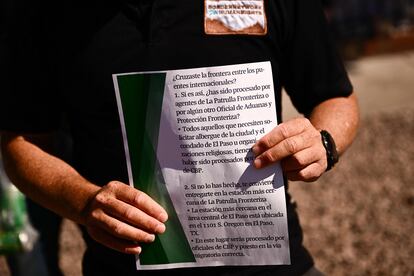

The streets around the church, which has come to symbolize the eternal border crisis, were cleared in a matter of 24 hours. At 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday, several unidentified individuals began handing out flyers urging illegal border crossers who had not yet surrendered to the authorities to urgently do so. The brochure also warned them of dire consequences if they chose to remain in limbo.

Thus began what the bureaucrats, with their talent for euphemism, had dubbed a “localized law enforcement operation.” In the afternoon, about 20 armed men insisted that the migrants should run to “be processed,” in a move that was denounced as intimidation by local NGOs. Hundreds of them, persuaded by members of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Service, lined up until sunset to meet with immigration officials in a white building surrounded by barbed wire.

Many left there with a handful of stapled papers, known as the Alien ID. The documents include a date and a place in the United States where they must appear before an immigration judge. Some were given an appointment as early as the end of the month. Others, as late as November 2026. Like so many other ins and outs of the tortuous processing system, why the timelines differ so much remains a mystery.

Dozens of them still had not been let out of the building almost a day later, and their friends and relatives anxiously awaited their fate inside the church. The rest, an amount impossible to determine, were deported straight back to Mexico, according to what other migrants, relatives, and friends told this newspaper.

The Alien ID allows migrants to move freely in the United States, but not to work: that permit has its own mysterious requirements. Some migrants choose to travel to places like New York or Orlando, to stay with those who arrived there before them. But a particularly popular destination seems to be Denver (Colorado), about a nine-hour bus ride away ($90) where, rumor has it, local authorities are willing to help migrants, including paying for tickets to other parts of the country.

Once the sidewalks had been cleared, an army of cleaners showed up to get rid of what had been left behind: blankets, food scraps, sandals, T-shirts... And that was when Edixon and Milena showed up, hoping to find “a community” of which only the leftovers remained. They didn’t know how they were going to find food, if there would be room in the shelters for them, if it was better to turn themselves in or not, or where to get the $120 that a thug asked them with the false promise of getting them a legal permit.

On Thursday, all eyes will be on El Paso as Title 42 comes to an end. Starting Friday, border apprehensions, which have recently climbed to 8,000 people a day, are expected to rise to over 10,000. Title 42 will be replaced with Title 8 again, but with a new twist: asylum applications will be denied to migrants who show up at the border without having previously requested asylum through a mobile application called CPB One.

In the meantime, the mayor of El Paso has unveiled a brand-new temporary migrant shelter inaugurated in a vacant high school on the outskirts of town. It was his way of stating that the situation is under control. During the media event he insisted that “the border was closed yesterday. It’s closed today. And it will continue to be closed on Saturday.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.