Why don’t we know who won the US midterm elections yet?

State vote-by-mail laws, the Georgia runoff and the tight result are delaying the outcome

In the 2020 presidential elections – held on Tuesday, November 3 – Joe Biden’s victory couldn’t be declared until Saturday. Two years later, it may take even longer for the midterm election results to be known. This is due to the huge amount of mail-in ballots that have yet to be counted, the different vote-processing systems used by each state, a lack of election workers, recounts in tight races and runoff elections in Alaska and Georgia, among several other factors.

At this point, both the Republican and Democratic parties have a chance of winning both the Senate and the House of Representatives. While the Republicans are favored to win the 218 seats needed to control the 435-seat House, this is by no means guaranteed. At the moment, Democrats are only a few seats behind. If Republicans lose their lead in a handful of districts in Colorado, Oregon and California – where the vote tallies are yet to be complete – the Democratic Party may be able to keep control of the House. As of Friday, the number of confirmed races is 211-198, in favor of the Republicans. Results are pending in 26 districts.

As for the Senate, there are three seats left to determine which party will control the 100-seat upper chamber. Arizona has been won by the Democrats. And Nevada is still counting votes, with the candidates in each state separated by tiny margins. In Georgia, as neither the Democratic nor Republican candidate garnered more than 50% of the vote, given the state rules, a runoff election will be held on December 6. In 2020, a second round was also held, which saw the Democrats win and take control of the Senate.

Counting millions of ballots is slowed down by the US’ archaic voting system. There are no common rules for the entire country – each state regulates the electoral process in its own fashion. House districts are often carved up along partisan lines – a strategy known as “gerrymandering” – with varying regulations regarding what is required from citizens to vote.

It’s also important to note that the midterm elections don’t simply encompass the election of politicians at the federal level. On Tuesday, for instance, Americans voted for governors, lieutenant governors and state legislators in 38 states, as well as for commissioners, judges, prosecutors, school board members, mayors, city councilors and other public servants across the country. American ballots can be several pages long, with dozens of options.

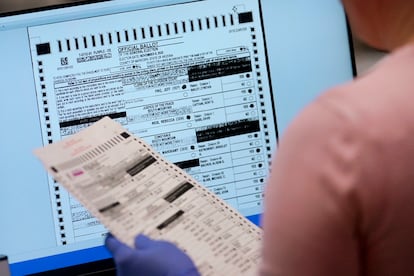

Mail-in voting rules are a major source of delay. In most of the 50 states, only those that arrive before the polls close are admitted… but there are states that admit them days later, so long as they were mailed before or on election day. For example, in the case of Nevada – a state of 3.1 million inhabitants – ballots were sent to all registered voters and are valid so long as they arrive at voting centers before Saturday, November 12. And, once these mail-in ballots arrive, not only do they need to be counted: an entire voter-verification process must take place, which requires election workers to confirm signatures. Voters may even be contacted “by letter, telephone or email” should an error be detected – there is an opportunity to correct information until Tuesday, November 15. With a resounding result in favor of one candidate, such a winner could have been determined earlier, but as the race is extremely tight, every vote counts. Obviously, this kind of system could be improved.

In Arizona, Maricopa County is famous for delays. For starters, despite the fact that the county is the second-largest electoral jurisdiction in the country, it has limited resources to count the large volume of ballots. While mail-in ballots do need to arrive before the end of election day, this results in thousands of ballots showing up at the last minute, overwhelming election workers, who have to go through the same verification process that is utilized in Nevada.

This year – in addition to the usual problems – tabulation machines broke down, requiring hundreds of thousands of votes to be processed manually. More than seven million people live in Arizona.

Nevada and Arizona are certainly not anomalies. In Washington, Oregon and California, similar systems are employed. While Democrats tend to win these states by large margins, usually there is no need to wait for the final vote tabulation to know who won the elections. But in swing districts, or in mayoral races, delays are common, especially as millions of West Coast residents tend to vote by mail. In Los Angeles, for instance, it may take until the end of November for the mayoral race to be decided, due to the shortage of poll workers and the stringency of the verification process for mail-in ballots.

The delays and the incidents that take place during the count often give losing candidates ammunition to launch baseless hoaxes about electoral fraud. Former president Donald Trump already did this in 2020, and he’s already begun to sow suspicion about the 2022 midterms, after several of his hand-picked candidates lost in tight races. This past Thursday, he wrote on his Truth Social account that the Republican majority in the Senate depends on “whether the elections in Nevada and Arizona are rigged or not.”

The ranked system employed in Alaska and Maine – along with Georgia’s two-round system – will prevent Americans from knowing the final composition of the House and Senate for up to a month after election day. In Alaska, far-right Republican Sarah Palin – best-known for her disastrous performance when she was the Republican vice presidential nominee in 2008 – is challenging incumbent Representative Mary Peltola Akalleq, of the Democratic Party, in a result that won’t be known until all the second choices of the third and fourth-place finishers are added up and transferred to each woman. Palin and Akalleq garnered 26.6% and 47.3% respectively. A similar situation is occurring in one of Maine’s congressional districts, with Democrat Jared Golden at 48.2% and his Republican rival close behind at 44.9%. A calculation will now need to be done to determine who was the second preference of the independent candidate’s voters, who make up 6.9% of the total.

In Georgia – as in 2020 – a runoff election between the top two finishers will be held on December 6. The Libertarian Party candidate garnered 2% of the vote, leaving Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock and Republican candidate Herschel Walker each just shy of 50%. Star politicians and millions of dollars in campaign donations will now likely flock to the “Peach State” to support each man. Warnock, a former preacher, has the advantage over ex-NFL player Herschel Walker, who has been accused of spousal abuse. But whatever the result is, you can bet that it will take a long time to come out.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.