Coronavirus pandemic revives the culture and economy of the world’s southernmost town

Lockdown restrictions in Puerto Williams, Chile, gave young people the opportunity to learn the ancestral crafts and the language of the Yaghan people

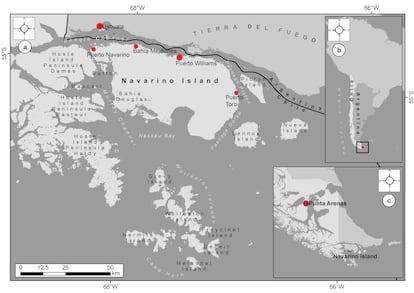

On March 21, 2020, the first case of the coronavirus was recorded in Puerto Williams, a small Chilean town that is famed for being the southernmost settlement in the world and which has been home for the past 7,000 years to the Yaghan indigenous people. Two days later, the authorities closed maritime entry points and airspace, limited economic activity to essential business only and ordered a strict lockdown. According to Maritime Studies, one of the leading social sciences and humanities publications in the world, the quarantine measures had the effect of reviving some ancestral cultural practices that had been in danger of disappearing for some time, including traditional artisan work and use of the Yaghan language. The lockdown also strengthened intergenerational links in the community and led children and young people to once again feel identified as indigenous people.

The report documented the way of life of 94 members of the Yaghan community in Puerto Williams during the harshest months of the pandemic. Gustavo Blanco, a professor at the Austral University of Chile’s Institute of History and Social Sciences and the lead author of the study, said the lockdown reinforced the relationship between the elders in the community and the newer generations. This renewed bond helped to “revive artisanal practices with palm fiber that had been in decline,” says Blanco. “When you are stuck indoors at home for months, you have the opportunity to get to know aspects of your culture that are being lost and learn how to recover them.”

María Luisa Muñoz, president of one of the Yaghan associations in Puerto Williams, agrees. “During the quarantine we returned a little to the way of life of our ancestors; we rediscovered our relationship with animals, with the natural world and with our roots,” she says. “I was able to teach my grandchildren the art of basket-making. We went out to gather the reeds and then went home to weave the baskets in the same way our ancestors did.”

The recovery of these ancestral artisanal techniques has become a form of employment, which besides protecting the Yaghan people’s cultural legacy has also provided economic resources for families who lost their jobs during the lockdown, many of which relied on the tourism industry. In March 2021, a year after the first case of Covid-19 was diagnosed in Puerto Williams, the Yaghan ran intensive workshops so that more children could perfect their reed-weaving techniques. “Over the course of a month, I was able to learn all of the traditional steps from the most experienced mothers and grandmothers, from seeking out the reeds to the preparation of the vegetable fiber with fire, and the use of the baskets to collect shellfish and other seafood,” another community leader said in a message published on social media.

As in the rest of the world, lockdown in Puerto Williams also led to an increase in the use of digital forms of communication and allowed the local community to forge links with other indigenous peoples in Latin America and with the Yaghan diaspora. Through these conversations on Zoom and other platforms a project to recover the Yaghan language was born. Muñoz explains that before Spanish colonization, the Yaghan community consisted of around 4,000 people speaking five distinct dialects. Today, only one of these dialects survives and few people are able to speak it. “Some of the elders know the language and the pandemic allowed them to teach it to their children and grandchildren. We didn’t want it to die out. That’s why we’re working with a Yaghan linguist who lives in Europe to create an alphabet and a text book that will help us to write in our language and teach it in the schools in our community,” says Muñoz.

With the same desire to preserve ancestral culture, by the end of 2019 community leaders had compiled the stories and experiences of the Yaghan elders in a book entitled My grandparents told me, which was published with the help of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. The pandemic put a temporary stop to events to promote the book, but with restrictions now being eased the Yaghan are able to start planning more events.

These ways of reviving the Yaghan culture, says Blanco, show that “when it seems as if everything has ground to a halt in times of lockdown and social distancing, in reality there are issues that spring up and others that gather pace, leading to new experiences and knowledge.” The final paragraph of the Maritime Studies report, which was conducted by a collaboration between the Center for High Latitude Marine Ecosystem Dynamics Research (IDEAL), the Austral University of Chile and the Martin Gusinde Anthropological Museum in Puerto Williams, reads: “If there is any lesson to be had in these hard times, it is that there is no single, linear way of understanding the effects of the virus; as it brings restrictions, threats, and death, it is also ushering in new forms of political action, new ways of communicating, and new stories for the future.”

Muñoz adds some nuance to the conclusion of the study. Fortunately, the coronavirus pandemic has caused only one fatality within the community, but the life it claimed was that of one of its most beloved leaders. “The virus has caused us harm, we would never have wanted it to reach our community and we are all very sad about the death of Martín González, an artisan,” she says. “But we must also look on the bright side of the pandemic. It has given us a way to revive our culture and has fostered acts of cooperation and solidarity.”

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.