Email bombardments: Russian cyber espionage campaigns target NATO

Hacker groups such as Fighting Ursa and Cloaked Ursa attacked military, diplomatic, public and private entities in European countries with infected emails in 2022 and 2023

There’s another war with Russia, far from the frontlines, which is being waged on a daily basis. It’s fought in the digital trenches, through infected emails. NATO members are already deeply involved and on high alert.

Western intelligence services and cybersecurity firms are fighting hacker organizations — such as Fighting Ursa (APT28) and Cloaked Ursa (APT29) — which the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom link to the Russian state. The intense activity of these groups means that workers in both the public and private sectors of NATO nations run the risk of opening the doors to the Kremlin’s cyber spies, simply by clicking on a malicious message.

“Cyberspace is tested at all times and malevolent actors seek to affect the infrastructure of NATO members, interfere with government services, extract intelligence and steal intellectual property,” a NATO spokesperson tells EL PAÍS. They corroborate that the relationship between the Russian state with groups such as APT28 and APT29 is “well documented” and that the Alliance doesn’t hesitate to point out the links they maintain with the Russian intelligence services. “[NATO members] have also attributed a series of cyber events to groups associated with the Russian state and have imposed sanctions on individuals associated with them,” the organization emphasizes.

Since 2022, some 13 cyberattacks have been officially attributed (or have at least been considered “probable”) to Fighting Ursa, with two attributed to Cloaked Ursa. This is according to data collected by the CyberPeace Institute, a non-governmental organization specializing in cyber threats, which receives funding from companies such as Microsoft and Mastercard. The main targets of these hacker groups were entities based in Ukraine (mostly in Kyiv), but operations were also recorded against institutions located in Poland, the United States and Belgium (specifically, Brussels). Eight of these attacks were aimed at data extraction or espionage, according to the NGO. In most cases, emails were the main means of infiltration.

“All cyberespionage groups aim to steal information that allows their respective states to obtain some type of geopolitical or strategic advantage,” a spokesperson for the National Cryptologic Center (CCN) — attached to Spain’s National Intelligence Center — tells EL PAÍS.

This organization believes that these hackers are probably looking for information that supports Russia’s war efforts, given their links to that country’s military and intelligence structures. “In the specific case of APT28 and APT29, the usual targets in the public sector are government institutions and critical infrastructure. In the private sector, the common objectives are defense, technological, energy, financial and transportation companies,” the CCN notes.

Outlook, car sales and poisoned PDFs

An investigation by cybersecurity firm Palo Alto Networks, however, estimates that at least 30 military, diplomatic, government and private entities in NATO countries were the targets of Fighting Ursa’s malicious email campaigns, in a total of 14 countries in 2022 and 2023. A spokesperson for this company has detailed exclusively to EL PAÍS that six of the targets were military, three were diplomatic, while the rest belonged to the public or private sector. Specifically, 26 of the targets were European, including embassies and ministries of Defense, Foreign Affairs, Interior and Economy, as well as at least one NATO Rapid Deployment Force.

In the context of this operation, institutions in Ukraine, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (which are included in the 14 affected countries, despite not being members of the Atlantic Alliance) were also attacked. “The main objective of these attacks is to obtain the information necessary to impersonate [certain institutions and individuals]. This allows the attacker to illicitly access and maneuver within the network,” a spokesperson for the cybersecurity firm tells this newspaper. Palo Alto Networks highlights that they don’t know if any of these campaigns have managed to extract any type of critical information.

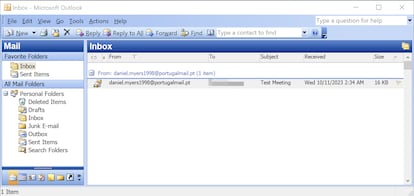

The company warns that, in some cases, these emails don’t even have to be opened to contaminate a computer. In fact, those used for the latest Fighting Ursa campaigns are based on a “vulnerability” within the Microsoft Outlook program, which is automatically activated when the victim receives a “specially crafted” email. The company emphasizes that this software flaw can leak information without user interaction, allowing the hacker to spoof credentials and subsequently authenticate to your network.

In the case of Cloaked Ursa, experts from the CyberPeace Institute explain to EL PAÍS that the two attacks officially attributed to it were directed against the NATO headquarters in Brussels, but also against government entities belonging to the European Union. “Cyberattacks against targets outside the two belligerent countries (Russia and Ukraine) demonstrate how operations can extend to nations [that are participating] through military or humanitarian aid, financial sanctions, or political support,” observes a CyberPeace Institute spokesperson.

The hacker group has also tried to infiltrate NATO diplomatic missions in Ukraine on numerous occasions (including the Spanish, Danish, Greek and Dutch delegations). In fact, Palo Alto Networks’ investigations have recorded two such operations in 2022 and 2023, in which the identity of diplomats was impersonated through fake emails containing malicious files. The first format contained a contaminated version of an advertisement for the sale of a BMW, which a Polish official was sending around at the time. The second consisted of simulated invitations from the Portuguese or Brazilian embassies: it contained PDF files contaminated with programs capable of extracting information stored in both Google Drive and Dropbox.

“Cloaked Ursa conducts phishing attacks by leveraging lures to force targets to click on emails, often playing on people’s curiosity. Whether it’s [an] advertisement for a low-cost BMW for diplomats, or using the topic of the earthquake in Turkey, or Covid-19. They use these email subject lines to entice their targets to click on the links,” a Palo Alto Networks spokesperson notes. The company claims that Cloaked Ursa used “publicly available” embassy email addresses for approximately 80% of the targets of the BMW operation, while the remaining 20% would have been collected as part of other Russian intelligence operations.

A NATO spokesperson has responded to EL PAÍS, saying that she has no evidence that the Atlantic Alliance’s classified networks have been compromised by actors linked to these organizations during the aforementioned operations. Likewise, she highlights that “in recent days” the allies have individually taken new measures to deactivate a “cyberpiracy network” related to APT28. Along similar lines, a spokesperson for the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to this newspaper, affirming that “to date, no attempted attack through this email mechanism or any other has been successful at [targeting] any headquarters, including the one in Kyiv.” They stated that these types of threats are automatically filtered and eliminated by “corporate antivirus solutions.”

The problem of authorship

Although there are other Russian hacker organizations (such as Conti or People’s CyberArmy), only Fighting Ursa and Cloaked Ursa have been directly linked to the Russian state. Specifically, experts from the CCN, Palo Alto Networks and the CyberPeace Institute agree that Cloaked Ursa must be connected to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), while Fighting Ursa has been linked to the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff (GRU) of Russia. Experts emphasize that these links have also been publicly denounced by the U.S. and British governments, as well as by technology conglomerates such as Microsoft.

So why is there no retaliation against the Kremlin, if so many entities attribute these attacks to them? The problem is having enough certainty to make a direct accusation. Mira Milosevich — a senior researcher for Russia, Eurasia and the Balkans at the Elcano Royal Institute in Madrid — explains that an expert opinion about these cases often takes a long time to formulate, as it’s quite difficult to find conclusive evidence. “Authorship is one of the biggest problems in this type of cyberwar. A good hacker hides their actions. For example, the physical territory usually doesn’t coincide with the country where the group of people who are carrying out the campaign come from. If an attack comes from Venezuela or Cuba, this doesn’t necessarily mean that [those countries’] governments are behind it. No one can prove that Vladimir Putin has ordered a cyberattack against NATO. No state speaks publicly about the hackers it [employs],” the expert says. Along these lines, she points out that hackers deliberately leave “crumbs,” with the intention of confusing anyone who wants to investigate an attack.

For their part, the CCN agrees that the attribution of cyberattacks based exclusively on technical evidence is “one of the most complex tasks today.” However, they add that regardless of the geographical origin of the attacks carried out by both cyber espionage groups, what does seem clear is that they must be sponsored by a state. “The infrastructure and tools they use — together with the complexity and objectives of their attacks — are only within the reach of highly-dedicated groups, with many resources and extensive technical knowledge. This is only possible if they operate as part of the structure or with the support of an intelligence service,” a spokesperson for the National Cryptologic Center assures this newspaper.

NATO’s response

The CCN indicates that NATO members have significantly increased monitoring and detection capabilities in recent years. “More and more information is shared about hostile actors, since they’re global threats that can only be faced jointly,” the entity states.

“NATO has designated cyberspace as a warfighting domain and has recognized that an adverse cyber campaign could trigger the Alliance’s collective defense clause. While the allies are responsible for the security of their national cyber networks, the organization supports their cyber defenses by exchanging real-time information on threats and providing training and expertise,” a NATO spokeswoman tells EL PAÍS.

The spokesperson adds that the Atlantic Alliance also carries out the largest cyber defense exercise in the world and has teams of experts prepared to help allies in the event of a cyberattack. “As most networks are privately owned, we’re also expanding our links with the industry. Cyberspace is an area in which the Alliance will continue to operate and defend itself as effectively as it does in the air, land and sea,” the organization states.

Mira Milosevic adds that, since the cyberattack on Estonia in 2007, NATO has been contemplating military responses to these events. However, she believes that the development of technological capabilities is “so accelerated” that laws normally lag behind, which creates bureaucratic barriers. “The first phase of hybrid warfare is the control of cyberspace and information. In the case of Russia, this is very well developed. Valery Gerasimov — chief of the Russian General Staff — has [written] an article that says that the difference with previous wars is the control of this space,” the expert explains to EL PAÍS.

That said, the researcher at the Elcano Royal Institute believes that the weakest link in the cybersecurity chain is always the human factor. Along with emails, the Russians have developed a whole repertoire of means to hack mobile phones and access confidential or sensitive information digitally. “The Russian [government] never sleeps and always spies. To paraphrase a well-known quote from Stanislav Levchenko (a Russian KGB officer who defected to the U.S.), if you look for your technological vulnerabilities, you will find the heirs of the KGB,” the expert jokes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.