Fighting pedophilia at the expense of our privacy: The EU rule that could break the internet

The European Parliament and the Council are discussing a regulation that would ensure all messages get scanned for child pornography and which is perceived by many as a threat to basic freedoms

Sexist violence is one of the great scourges of society. But would we be willing to have a security camera recording 24 hours a day in every room in every home to eradicate it? Brussels proposes a similar dilemma to combat the digital dissemination of child pornography. The European Union is going to decide in the coming weeks whether to approve a regulation that forces technology companies to review users’ private communications to detect child sexual abuse material. If it goes ahead, it will involve the automatic scanning of every message, photo, video, post or email exchanged on European soil whenever there is suspicion that it contains illegal material.

Some, like Apple, have their reservations about this initiative as they consider defending user privacy a priority. This position has earned the company a negative campaign in the United States, where, as in the United Kingdom, similar regulations are being discussed. The company prefers not to comment on either the campaign or the regulation.

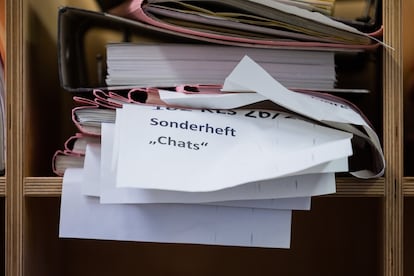

Hundreds of academics and engineers and non-profit organizations such as Reporters Without Borders, as well as the Council of Europe, believe that the Child Sexual Abuse Regulation (CSAR) would mean sacrificing confidentiality on the internet, and that this price is unaffordable for democracies. The European Data Protection Supervisor, who is preparing a statement on this for late October, has said that it could become the basis for the de facto widespread and indiscriminate scanning of all EU communications. The proposed regulation, often referred to by critics as Chat Control, holds companies that provide communication services responsible for ensuring that unlawful material does not circulate online. If, after undergoing a risk assessment, it is determined that they are a channel for pedophiles, these services will have to implement automatic screening.

I wonder who exactly is paying for the ads and what their specific business interests are. https://t.co/KFKjs7Vc37

— Matthew Green (@matthew_d_green) September 23, 2023

The mastermind behind the billboards and newspaper exhortations calling on Apple to detect pedophile material on iCloud is, reportedly, a non-profit organization called Heat Initiative, which is part of a crusade against the encryption of communications known in the U.S. as Crypto Wars. This movement has gone from fighting against terrorism to combating the spread of online child pornography to request the end of encrypted messages, the last great pocket of privacy left on the internet. “It is significant that the U.S., the European Union and the United Kingdom are simultaneously processing regulations that, in practice, will curtail encrypted communications. It seems like a coordinated effort,” says Diego Naranjo, head of public policies at the digital rights non-profit EDRi.

There are some technology companies that do welcome Chat Control. Notable among them is the American business Thorn, created by actor and businessman Ashton Kutcher and his then-wife, Demi Moore. A recent journalistic investigation has revealed that the EU Commission exchanged sensitive information on the progress of the regulation negotiations with the company, which presents itself as a non-profit but carries out significant lobbying work and has commercial interests in the matter. Thorn’s flagship product is a software that is based on Microsoft’s PhotoDNA and supported by AWS, Amazon’s cloud division. The program is designed to detect child abuse by cross-referencing hash values (a type of alphanumerical license plate) of images and videos uploaded to the internet against a database of millions of known images of child sexual abuse material.

A delicate balance

“It is incredible that we still do not have regulation in the EU on online child abuse. I feel like a pioneer with this proposal,” said Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson in a recent interview with this newspaper. “Of course children must be protected, the question is how,” responds Carmela Troncoso, a researcher at the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne and leader of the team of scientists that developed the privacy protocol for the Covid-19 tracking applications. “There are two questions to ask about this proposal: first, whether it is really going to protect children, and second, whether it can be done safely. And the answer to both is no.”

“The main problem that this technology poses to citizens is that pedophile content will be detected using automatic artificial intelligence (AI) tools,” says Bart Preneel, a professor of cryptography and privacy at the Catholic University of Leuven and author of a technical report for the European Parliament in which he exposes the shortcomings of the system. “Thorn says their system gives 10% false positives. Since Europeans exchange billions of messages daily, that means that tens of millions of people will be charged every day. Even if they are innocent, their information will be processed and stored by security forces, and if it is leaked, their reputation will be impacted.”

Every time we write a message on platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram or Signal, that communication is encrypted. Only the recipient has the key to open it. This is what is known as end-to-end encryption, a mechanism that guarantees that no one other than the sender and receiver can access the content. The proposed EU regulations maintains that it is not necessary to end encryption: it would be enough to review the messages on the device itself before sending the content and when it reaches its destination.

“The argument that this technology does not break encryption is based on tremendous technical ignorance,” says Troncoso. “If you look at it before, even if you don’t touch the algorithm or the key, of course you are breaking the encryption. It is like saying that if someone reads a letter before putting it in the envelope and the envelope arrives sealed at its destination, confidentiality is not broken.”

@X_net_ Origin: https://t.co/9UaCwJZKdH pic.twitter.com/kycKsqji4P

— Rosanna Cantavella / @cantavest@hcommons.social (@cantavest) October 5, 2023

“Companies are forced to break their own encryption to scan messages before they are sent to their recipient. The problem is that there is no way to implement those methods and preserve privacy at the same time. And if you break the encryption, you invite hackers in. There are no backdoors that only the good guys can use,” argues Andy Yen, founder and CEO of Proton, the developer of the Proton Mail encrypted email service. “Chat Control is about combating the serious problem of illegal content by creating of another serious problem: ending the right to privacy,” adds Yen. However, a legal report commissioned by EU institutions concludes that the regulation under discussion could “lead to permanent de facto surveillance of interpersonal communications”, which is illegal in the EU.

The scanning techniques proposed by the EU are also easy to evade. As Professor Preneel explains, it would be enough to change a few bits in the images that are stored in the database against which communications would be compared, and the algorithm would be unable to establish a match.

Open negotiations

Brussels has been working for two years on a regulation that allows scanning private communications to combat the dissemination of child abuse material, which in 2022 alone generated 1.5 million reports from internet companies collecting five million videos and photos and grooming activities. In May last year, the Commission proposed a draft regulation on which the European Parliament and the Council have been working since then.

Spain currently has the EU rotating presidency and the idea is to approve the regulation before the end of its term on December 31, although it is likely that the deadline will not be met. At the moment, the draft is pending debate in the European Parliament’s Civil Liberties Committee, which will vote on the text on October 26. “Negotiations between the groups are going well. What we are debating now are the detection orders,” explained the European People’s Party MEP Javier Zarzalejos, rapporteur of the proposed regulation. This means when and how internet service providers that have failed to stop the spread of child pornography through other means will be forced to scan communications. “It is the instrument of last resort and greatest intensity in terms of the detection capacity of this type of material. The idea that we are going to be subjected to massive and systematic scanning of our communications is absurd and is not going to happen. “It is neither technically possible nor makes any sense.”

This video has got a lot of reactions. Good.

— Ylva Johansson (@YlvaJohansson) October 2, 2023

It is an emotional subject because it is about stopping sexual violence against children.

But the facts of my proposal are clear, and I will always defend them.

Because this is about protecting children - and only that. https://t.co/mN3CdNSkyK

The document is also being reviewed in the Council, the EU body that brings together representatives of the governments of its 27 members, which is expected to debate it on October 19. There is no consensus here either. A dozen countries (Germany, Austria, Estonia, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic and Sweden) oppose the text presented by the Spanish poresidency. Among the main defenders of the proposal are Hungary, Finland and Spain.

As published by Wired in May, citing official sources from the government of Spain, Madrid’s position is that “it would be desirable to legislatively prevent service providers from implementing end-to-end encryption.” Spain’s Interior Minister has denied that allegation in a conversation with this newspaper.

When the European Parliament and the Council establish their position, it will be time for the so-called trilogues, a negotiation between these two institutions and the Commission that will finish shaping the final document.

Digital solutions for a physical problem?

Another criticism that the regulation faces is that it is trying to solve with technical means something that is not limited to the digital field. “Child abuse is not a technological problem, there is no such thing as online abuse. These crimes are committed in the physical world, they cannot be fixed with technology,” says Troncoso.

The regulation promoted by the Home Affairs Commissioner does not contemplate measures such as the reinforcement of mechanisms so that minors can report attacks or social assistance to monitor their family environment and friends.

“It is extremely serious that in the proposed regulation there is not a single line of prevention or strategies to socially address sexual abuse. The law uses abuse against children to attack the structure and architecture of the internet,” says Simona Levy, from the Xnet collective, which has been very belligerent with Chat Control.

So what happens if the regulation enters into force as it is currently worded? “It would be very bad news. The dichotomy between security and privacy is false. In general, the more privacy, the more security, and not the opposite. Anyone who has lived in a dangerous country has an intuitive knowledge of how privacy is used to protect individuals,” reflects the philosopher Carissa Véliz. “When we give up privacy we are losing security and eroding democracy. In a police state in which there was total surveillance it would be impossible to commit a crime, but at what cost?”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.