Now what? National election leaves Spain in a labyrinth

The two right-wing parties did not win enough seats to form an absolute majority, and the possibility that the Popular Party and the far-right Vox could make pacts with other parties can be completely ruled out

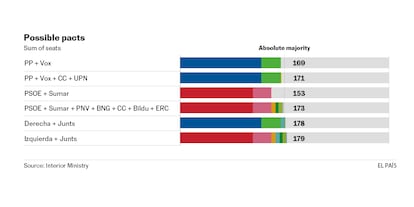

The parliament that emerged from the national election held in Spain this Sunday and which will begin a new term on August 17 will be the closest thing to a political labyrinth. Together, the two right-wing parties did not win enough seats to form an absolute majority (for which 176 seats are needed), and the possibility that the Popular Party (PP) and the far-right Vox could make pacts with other parties to reach it can be completely ruled out, given Vox’s unwillingness to work with regional nationalist groups (the far-right party advocates a strong centralized government). The left-wing bloc that has carried Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s government for the past four years did not win the necessary 176 seats either. For the Socialist Party (PSOE) and Sumar (a grouping of 15 small leftist parties) to form a new coalition government, they would have to come to some kind of agreement with Junts, a Catalan party founded by Carles Puigdemont, who pushed an illegal independence referendum in 2017 and fled to Belgium.

Forming parliamentary majorities has been a puzzle in Spain since the country effectively abandoned bipartisanship in 2015. Eight years later, although the two main parties concentrate most of the votes, the labyrinth of Congress has become even more complicated, and it is very difficult to conjecture what the way out may be. With the current distribution, the left would have a better chance of forming a majority. The right being able to do so seems impossible, provided that the formula includes Vox. The only possibility would be if, in order to avoid a repeat election (like the ones in 2016 and 2019), the Socialists reached some kind of agreement that would allow the PP to assert its status as the most voted political formation. Below, we analyze some of the possible pacts and agreements.

What the left needs to hold onto the government

The Catalan independence movement came out seriously damaged after Sunday’s vote. The 23 deputies it gathered four years ago between the pro-independence Catalan Republican Left (ERC), Junts and CUP has been drastically reduced to 14. In spite of this important setback, the pro-independence parties once again occupy a central place in the politics of alliances. And this time around, ERC is not the only one that must be taken into consideration; there is also a hypothetical partner that is much more complicated, Carles Puigdemont’s party Junts.

The parties that in the last four years have supported — with discontinuities and depending on the moment — the coalition government won 172 seats: PSOE (122), Sumar (31), ERC (7), the far-left Basque Bildu party (6), the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) (5) and the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG) (1). To be voted in as the new prime minister at the investiture vote, an absolute majority (176) is needed in the first vote or a simple majority (more votes for than against) in the second. Sánchez achieved it four years ago through the second formula, by a two-vote difference and thanks to the abstention of ERC and Bildu. This time, Sánchez would need those two formations to give him their favorable vote, which seems feasible, and at least the abstention of Junts. The latter is certainly problematic.

In these last four years, Junts has opposed Sánchez’s government with as much constancy and forcefulness as the national right-wing parties. Junts has voted against in almost all relevant issues. Reaching a possible understanding with the party of the former Catalan premier who pushed forward the independence referendum would certainly anger the right. “We will not make Pedro Sánchez the PM in exchange for nothing,” warned Miriam Nogueras, head of the Junts list, on election night.

Impossible for the right

Together, the PP and Vox have 169 seats, and they only have one safe seat they could add to their bloc, that of the Navarrese People’s Union. Another possible scenario would be the addition of the seat won by Coalición Canaria, a party that many associate with the PP because they are governing with them in the islands. But without the support of the PNV ― unlikely at this point — this combination of forces would still not be enough to raise Alberto Núñez Feijóo’s seats to the necessary 176.

The mainstream Basque nationalists of the PNV have never ruled out agreements with the PP, as they have already had them throughout history. But they have also made it clear that they would never enter into any formula that would have to count on the support of the far-right Vox. Moreover, an abstention by the PNV would not be enough, it would be necessary for it to give its affirmative votes for such a scenario to prosper. And considering the PNV’s tough fight against the left-wing EH Bildu ahead of regional elections to be held next year in the Basque Country, it would appear that the PNV’s refusal to mix with Vox in any way is not going to change.

An agreement with the Socialists

Feijóo said it numerous times during the election campaign, and he repeated it vehemently in his speech on election night on the balcony of the party’s headquarters: he called on Sánchez to let him govern. The chances of that happening are minimal, and even more so with such a narrow result in votes and seats. Sánchez also denied the possibility repeatedly during the campaign, as he understood that the PP was asking him for support in exchange for nothing.

Of course, if the deadlock persists and the possibility of a repeat election begins to take shape, some unforeseen twist could arise.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.