Juan Carlos lawsuit: Spain denies foreign ex-heads of state the immunity emeritus king is claiming in London

The British justice system must decide if the former monarch enjoys protection as a sovereign in the case brought against him by his former lover Corinna Larsen

If Spain’s emeritus king Juan Carlos I was a former head of state of a foreign country, and was accused in Spanish courts of harassment, illegal monitoring and libel – as he has been by his former lover, Corinna Larsen, in the United Kingdom – he would not be covered by sovereign immunity.

This is the central question of the lawsuit Larsen has filed against the former monarch, which is being heard by a court in London. The Monaco-based businesswoman, who used to be romantically involved with Juan Carlos, has asked for an injunction restraining the emeritus king from contacting her, following her, defaming her or coming within a distance of 150 meters of her.

At the end of December 2020, Larsen detailed the harassment that she claims to have suffered as part of her lawsuit, attributing the events to Juan Carlos I directly or to figures acting in his name. These included the former director of Spain’s CNI secret service, Félix Sanz Roldán. Larsen argued that the behavior was designed to persuade her to return a €65 million gift that Juan Carlos had transferred to her “irrevocably” in 2012, or to restart their relationship.

In the extensive lawsuit, the businesswoman related the alleged threats, electronic surveillance and monitoring that she claims she and her team of consultants were subjected to, as well as the series of allegations that was aimed at her. The consequences of all of this, according to the legal filings, were anxiety and distress that have required medical treatment, led to the deterioration of her relationships with her children and other relatives, and the loss of many of her wealthy clients.

But whether or not this case prospers depends on if Juan Carlos – as his lawyer argues – still enjoys immunity against prosecution as a “sovereign.”

In Spain, the norm that regulates the status of foreign leaders is an organic law on the immunity and privileges of states and international organizations in the country that was approved in 2015 under the administration of former prime minister Mariano Rajoy. According to this law, heads of foreign states are “inviolable when they enter Spanish territory, during the entire period of their mandate, regardless of whether they are on an official or private visit” and “will not be subject to any form of detention.”

Who is Corinna Larsen?

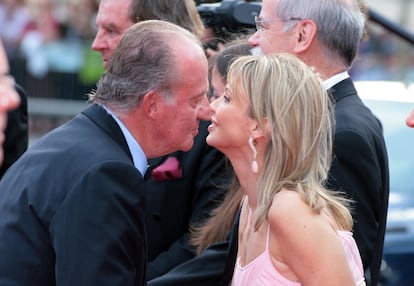

The relationship between Corinna Larsen and Spain’s then-king came into the public spotlight as a result of the 2012 accident that Juan Carlos suffered in Botswana, where they were both on a hunting safari. The incident damaged the monarch’s reputation and was partially behind his surprise decision to abdicate in 2014.

Larsen, a Monaco-based businesswoman who continues to use her German ex-husband’s aristocratic title, zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, made headlines in 2018 when recordings emerged in which she claimed she had been used as a front to conceal some of Juan Carlos’ wealth.

Juan Carlos I was investigated by the Spanish Supreme Court public prosecutor in connection with alleged kickback payments stemming from the construction of an AVE high-speed rail link from Medina to Mecca, and for other alleged offenses including bribery, perverting the course of justice, influence peddling and tax evasion. But in October prosecutors announced they were planning to shelve these probes.

But once they are no longer head of state, as is the case of Juan Carlos I, who abdicated the throne in 2014, “they will continue enjoying criminal immunity only in relation to the acts carried out during their mandate, in the exercise of official duties.” The law explicitly excludes genocide, forced disappearance, war and crimes against humanity from this immunity. Also excluded is immunity against civil suits like the one filed by Larsen against the former monarch over harassment claims. The law states that a former head of state “will continue to enjoy civil, work, administrative, commercial and fiscal immunity only in relation to the acts carried out during his mandate in the exercise of official duties,” with a series of exceptions made for different kinds of business and trade conflicts.

To drive home the point further, the 2015 law also states that “once their mandate is over,” former heads of state “will not be able to use their immunity in Spanish judicial bodies when it involves actions related to acts that were not carried out in the exercise of their official duties during their mandate.” In other words, under no circumstances will their private actions be protected by immunity.

This same argument was made at a preliminary hearing on Monday by the barrister representing Larsen, James Lewis QC, who said that no one can reasonably argue that the acts of harassment and persecution that Juan Carlos is accused of were carried out under the cover of his public functions – i.e., with the protection of immunity.

Former heads of foreign states will continue enjoying criminal immunity only in relation to the acts carried out during their mandate, in the exercise of official dutiesSpanish law on immunity of foreign leaders in Spain

Under Spanish law, the only judicial privilege Juan Carlos enjoys is aforamiento – the Spanish term for the protection offered to politicians, judges and others from prosecution in the country’s lower courts. In other words, any case against the emeritus king, whether civil or criminal, has to be heard by the Supreme Court. This rule, which also applies to Queen Letizia, Princess Leonor and the mother of King Felipe VI, Queen Sofía, was approved in July 2014, immediately after the abdication of Juan Carlos, to strengthen the royal family’s protection against prosecution in the lower court.

But the future of the lawsuit against Juan Carlos hinges on whether the court decides if the former monarch still enjoys immunity against prosecution. To reach a decision, British Judge Matthew Nicklin, who is overseeing the case, has called on “the Spanish state” to clarify whether the emeritus king is still a part of the royal family.

A lot is riding on this point. Sir Daniel Bethlehem, the barrister from the international law firm Clifford Chance who is representing Juan Carlos, has based his defense on the argument that the former monarch cannot be brought before the courts as he is still protected as he remains “sovereign” and “member of his household” under the Spanish Constitution, and as such enjoys immunity.

This means it is now up to a British court to review the legal armory the Spanish government built around Juan Carlos, when he abdicated the throne in June 2014. In other words, the court must decide what is the legal status the father of King Felipe VI has been enjoying for the past seven years.

When Juan Carlos abdicated, the Rajoy administration approved a law that – in addition to granting the emeritus king aforamiento privileges – made two very clear decisions: it gave Juan Carlos the lifetime use of the “honorary title of king” and made it clear that both he and queen Sofía would remain members of the royal family.

These are the grounds upon which Bethlehem based Juan Carlos’s defense at the preliminary hearing on Monday. But Larsen’s barrister, James Lewis, was swift to dismiss this argument, claiming “no one considers that Juan Carlos I maintains the rank of head of state” and that “it is an honorary title, such as those retained by former presidents of the United States.” With respect to whether Juan Carlos is part of the royal family, Lewis pointed out that the former monarch does not depend economically on Felipe VI, nor lives under the same roof, and as such cannot claim immunity. Indeed Juan Carlos has been living in Abu Dhabi since August 2020, after he left Spain in the wake of an investigation into alleged financial irregularities.

Both sides believe that the judge will reach a decision on whether or not Juan Carlos still enjoys immunity within two months. After all, Christmas is just around the corner, they say.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.