How your cat ended up on your lap: A book challenges the history of the domestication of the most popular feline

Archaeologist and anthropologist Jerry Moore reviews the findings that explain a relationship marked first by fear and then by mutual interest and admiration

Jerry Moore recounts how the question struck him one evening in his living room. This archaeologist and writer had his cat on his lap; he gazed at it intently, and pondered: “How on earth did this get here?” The answer to his question is Cat Tales: A History (Thames & Hudson), a vast and ambitious book, written from the perspectives of archaeology and anthropology, in which Moore takes us on a journey spanning from the Pliocene era of terrifying saber-toothed beasts to Instagram cat videos. It is a history of thousands of years of coexistence, from mutual predation to happy domestication, demonstrating that the question Moore posed has a very complex answer.

For decades, the narrative was unquestionable: the ancient Egyptians domesticated cats roughly 4,000 years ago. As rodent predators, cats guarded grain silos and were protected and admired. Families mourned their deaths, cat mummies were kept with reverence, and Bastet, the feline goddess, was venerated and appeared in sculptures and paintings as a protector of the home and family. From there to Moore’s living room, the leap seems logical: the cat is a useful and beautiful animal that was domesticated for human convenience and ended up stealing our hearts — and our laps.

However, archaeology has a habit of wresting narratives from the hands of historians. Moore, in fact, decided to explore the human-feline bond through archaeology because “much of the evidence for such relationships is not found in written histories or among living cultures, but underground,” he says. And underground, in a 2004 excavation at the Neolithic village of Shillourokambos in Cyprus, something was found that challenged conventional history: a 9,500-year-old joint grave where a human and a cat had been buried together, surrounded by offerings such as seashells and polished stones. The cat, only eight months old, rested less than half a meter from the deceased human. Their bones were arranged with care and attention.

That Cypriot grave has redefined feline history. For Moore, its significance goes beyond the dates. What Shillourokambos reveals is something more fundamental: the very nature of how cats and humans learned to live together.

“The concept of domestication, as artificial selection for specific traits and reproductive control, is very valuable,” explains Moore, also professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of California, in an interview with this newspaper. “However, it doesn’t seem relevant to understanding the earliest interactions between sedentary populations and wild cats attracted to the mice and rodents living in the granaries and storehouses of Neolithic settlements.” The author explains that, for him, mutualism is a better concept: “Both people and cats benefited from these new interactions, during the Neolithic and later.” Humans gained pest control, and the felines obtained a source of food and shelter. The cats became, as Moore explains, “companions [of humans] by their own free will.”

What’s fascinating is that cat domestication didn’t happen everywhere. Although agriculture spread globally, modern domestic cats all descend from a single species: Felis silvestris lybica, the African wildcat. Cats were attracted to rodents (particularly the invasive house mouse, Mus musculus) that infested human granaries in Europe. However, Moore explains that in Mesoamerica they didn’t have the specific mouse species, and therefore the mutualism never developed.

Cats were the last animals to be domesticated, long after dogs (around 30,000 years ago) and cattle (10,000 years ago). This domestication is unique because cats do not contribute to human sustenance, guarding, or labor, and the process did not initially involve human control of reproduction, as it did with other species. Cats were common traveling companions on ships (from Greek triremes to Spanish galleons) to protect food stores from rats. This, however, led to cats becoming invasive species on remote islands, decimating local wildlife, which remains a massive problem today, with 400 million domestic cats running rampant around the world.

Intimate enemies

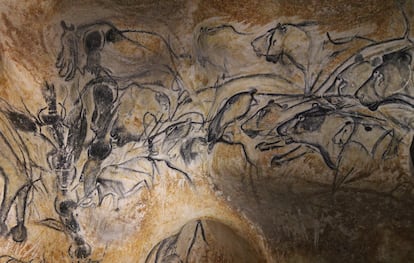

However, for thousands of years, humans and cats were enemies. In the Paleolithic caves of Chauvet, 32,000 years ago, early artists carved images of lions into the rock. Big cats and humans were mutual predators, and they still are, even in urban environments; the book cites dangerous pumas in Los Angeles and tigers in Mumbai. But what is extraordinary, Moore says, is that we are the only primates that actively live alongside feline predators. Our relationship with them, moreover, is different from the one we have with the other “great pet,” dogs; it is less hierarchical, less dependent on training, and more based on a strange balance between independence and closeness.

Why is this so? What is it about cats that has captivated millions of humans throughout history? Moore dedicates an entire chapter to exploring what he calls the “charisma” of felines; that magnetism that simultaneously attracts us, inspires respect, and sometimes terrifies us. “I think that fascination is deep and universal,” says Moore. Although we commonly apply the term “charisma” to other human beings, such as movie stars, rock musicians, and, less often, politicians, “the term applies to fascinating non-humans, such as lions, tigers, and other felines. That such widespread recognition exists among modern people from different cultures and nations suggests a deeply evolutionary origin.” In fact, a 2018 study did indeed find that big cats were considered the most charismatic animals.

A historical reflection of this fascination occurred in 525 BC. The Persian general Cambyses II knew of the Egyptians’ love for cats, so he captured hundreds of them and tied them to his soldiers’ shields. The Egyptian army surrendered without a fight in the city of Pelusium to avoid harming the cats. It is the first documented surrender for love of an animal in history.

The most curious thing is that the scientific evidence gathered in the book, from ancient DNA to modern behavioral studies, shows that the domestic cat is barely different from its wild ancestor. Moore sums it up like this: feline domestication is so slight that “the domestic cat is practically a docile version of the Felis silvestris lybica.”

“I’ve lived with several cats and I haven’t understood any of them,” the writer confesses, a sentiment likely shared by hundreds of thousands of humans who also currently have a cat in their lap. “How did this happen?” Moore wondered, observing his domestic cat. That mystery is, in itself, the central theme of the book. The answer, still contradictory and full of nuances, lies in hundreds of thousands of years of shared evolution, from predator to ally, from ally to god, and from god to companion.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.