Why abortion is deeply rooted in the history of humankind

Whatever the US Supreme Court says about termination, knowledge of how to prevent and end pregnancy has always been passed down through the generations, and will continue to be

The draft opinion leaked from the US Supreme Court last week, signed by Justice Samuel Alito, signaled the imminent overturning of the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that legalized abortion in the United States.

In defense of the opinion, the conservative judge wrote that “a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions.”

This may be correct insofar as those rights were not explicitly enshrined until the year that, under the pseudonym Jane Roe, a woman who wanted an abortion in Texas, a state of the US where it was illegal, filed a lawsuit against local district attorney Henry Wade. To be sure, the resulting decision, that the abortion laws of Texas were unconstitutional, changed the law across the country.

But long before and after this ‘capital-H Historical’ moment, abortion is ingrained in the fine print of America’s history, as it is in the history of all humankind.

As Slate recently noted, while 18th century American polymath and Founding Father Ben Franklin was not the only one to ever publish a recipe for abortion in a book, he was the first to do so in a book that became a bestseller: Frankin’s The Instructor (1748), an adaptation of a British tome, was considered a guide that every good American should have in their home to promote its proper functioning. The book was a general guide to know-how for the American colonies, which taught everything from mathematics to rules for letter-writing, including various formulas for home care, and also included this prescription for an unwanted pregnancy:

“For this Misfortune, you must purge with Highland Flagg, (commonly called Bellyach Root) a Week before you expect to be out of Order; and repeat the same two Days after; the next Morning drink a Quarter of Pint of Pennyroyal Water, or Decoction, with 12 Drops of Spirits of Harts-horn, and as much again at Night, when you go to Bed. Continue this 9 Days running; and after resting 3 Days, go on with it for 9 more.” [sic]

This detail in a work by the inventor of the lightning rod and bifocal glasses is proof that abortion has been present in the lives of women across the globe for centuries, and very specifically in the country where the practice is in danger right now. It is also an index of the dangers of aborting a fetus without regulation and/or proper medical care.

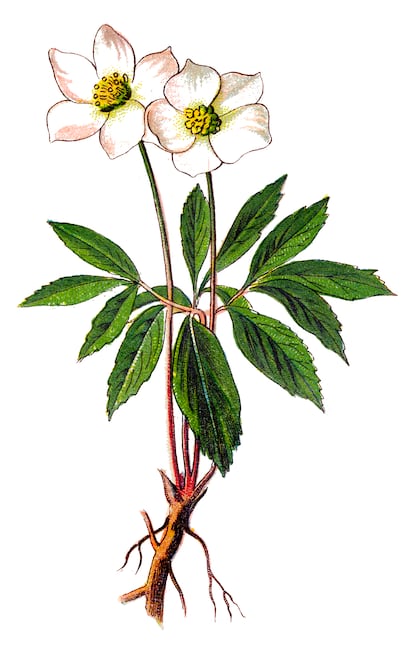

Natural remedies to bring on abortion have been common in all times and places: the Greeks and Romans in the 7th century B.C. had a plant called sylphium which, among its many medical properties, was given with wine to women to cause vaginal bleeding and expel an unwanted pregnancy.

Plants such as the highly toxic black hellebore, or fungi such as ergot have also appeared in historical records as effective abortifacients [substances that cause abortions].

As American historian John M. Riddle has argued, historical knowledge of abortion techniques is, by and large, not found in written archives - rather, it has belonged to an oral, female-centered culture where until around the 17th century, women were in charge of reproduction and information was passed down from grandmothers to mothers to daughters.

Therefore, to find written records you have to take a leap in time and read between the lines: in 1699, another guide for everything was William Mather’s Young Man’s Companion, and included a recipe for bringing on menstruation that recommended mixing ash plant (known for its laxative and slightly sedative properties) with “a few drinks of white wine under the full moon.”

In 1794, Carl Linnaeus, considered the father of botany, included five abortifacient herbs in his Materia medica. As the eighteenth century drew to a close, the place of abortion in private and public discourse in the United States began to change. In 1873 the Comstock Act was passed, a law that, among other rulings on sexual morality, made it a crime to obtain, produce or publish information on contraception, sexually transmissted infections or abortion. An illustrative moment in the life of this law occurred in 1887 when Sarah Chase, a single mother from New York and graduate of Cleveland Homeopathic College, was arrested while giving a talk on sexuality. Her talks were well-known; at the end she would have a series of contraceptive products for sale that were also available from her by mail order. The products included sponges and ‘vaginal enemas’ that promised to compel abortions. Her arrest occurred as she sold one of her products to a man who said he wanted to buy it for his wife; he was a police plant.

In her article The 19th Century Women’s Secret Guide to Pregnancy Control (Atlas Obscura, April 22), American writer Emily Cataneo explains that “courageous entrepreneurs” like Sarah Chase were critical vectors of knowledge on contraception and abortion during this particularly repressive period, knowledge that was “passed among women through coded language and whisper networks.”

As well as “restore menstruation”, other euphemisms for the actions of certain products included “cleansing the uterus” or “releasing the blockage”.

Many advocates and teachers of reproductive health suffered at the hands of the law as Chase did. Perhaps the most famous abortionist of the 19th century was New York’s Madame Restell, who advertised herself in mainstream newspapers as a “female physician” and sold “preventive powders” and “female monthly pills.” Restell committed suicide in 1878 after being charged with a crime under the new Comstock law. Sarah Chase was arrested on numerous occasions, but only went to jail once, when one of her patients died from an abortion.

Whether it was through hushed, behind-closed-doors remarks, discreet chats and home deliveries, recipes for botanical infusions, sponges or fake shopping lists, women have always passed on their knowledge to prevent or terminate a pregnancy: in other words, abortions and pregnancy control have existed since long before the legalization of abortion in the US in 1973.

Time and the evolution of the debate will tell whether people with uteruses will have to return to the secrecy of yesteryear, in countries where the laws are to be revised, such as the United States, or whether they will be able to continue performing these practices with institutional support and security, as is currently the case in Spain and increasingly so in Latin America.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.