Ground zero of America’s war on abortion

Oklahoma is the latest state to introduce a law to restrict the reproductive health rights of US women. Meanwhile, a leak has confirmed that the Supreme Court is preparing to overturn ‘Roe vs Wade’

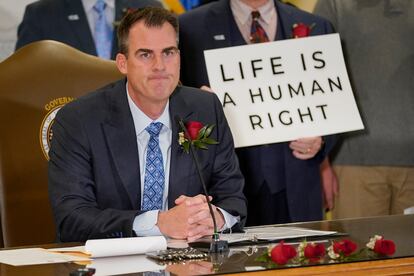

Ground zero of the war against abortion in Oklahoma is in a Tulsa suburb filled with single-story commercial buildings and half-empty parking lots. There, a health center called Tulsa Women’s Health Clinic has been resisting until the end as the state threatened to prohibit abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, a move which in practice amounts to an almost total ban. But their fight ended last Tuesday, when Oklahoman Governor Kevin Stitt – who says he wants Oklahoma to become the “most pro-life state in the country” – signed the anti-abortion law, which includes sentences of up to 10 years in prison and fines of up to $100,000 for any medical provider who performs an abortion. The law, which is called S.B. 1503 or the Oklahoma Heartbeat Act, also allows private citizens to sue anyone who “aids or abets” a woman seeking an abortion – from the doctor who performs the procedure to the taxi driver who takes the patient to the clinic.

Oklahoma is the latest of 22 Republican-led states to torpedo the right to abortion in the United States, which has been enshrined in law for half a century. Now the US Supreme Court may further bolster this conservative wave. According to a draft majority opinion that was leaked last week by the website Politico, five of the court’s nine judges are in favor of overthrowing Roe v. Wade, a precedent ruling which has guaranteed constitutional protection of abortion rights in the United States since 1973. If that happens, the ruling will return legislative power to the states, which will cause the country to split in two.

The Guttmacher Institute, an independent organization dedicated to research on sexual and reproductive rights, estimates that if the ruling is overturned 26 states (out of 50) will end up prohibiting abortion to some degree. One of the institute’s analysts in state politics, Elisabeth Nash, says that of this number, 22 Republican-led states have already enacted so-called “trigger laws,” restrictive laws or regulations that will come into effect immediately or in the months following the Supreme Court ruling. Of those, 13 states are moving towards a “total ban” on abortion. “Some of the laws are being challenged in court,” adds Nash. Another five states – Alabama, Arizona, West Virginia, Michigan and Wisconsin – have texts written before the Roe vs Wade sentence that have been waiting for more than 50 years for their moment to come into effect. “Nebraska and Indiana have not done anything yet,” says Nash, “but they have announced special legislative sessions” to study ways to restrict the right to abortion. In September, Texas approved the so-called “Texas Heartbeat Act” – the model for the Oklahoma anti-abortion law – that prohibits pregnancy terminations after the presence of a fetal heartbeat is detected.

This regressive wave threatens to leave women in the center of the country without access to abortion, with the exception of some states such as Colorado, New Mexico and, for now, Kansas. That “desert,” as Nancy Northup, president of the Center for Reproductive Rights, defines it, will be flanked by two pro-choice strips on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Amid the threat that Roe vs Wade will be overturned by the Supreme Court, some Democratic states have announced new laws to protect women’s rights to abortion, while others, such as New York, have offered to provide abortion services for out-of-state-patients.

The day after Governor Stitt signed the anti-abortion law, four volunteers – three women and one man – were stationed early in the morning outside the Tulsa clinic to help patients through. They wore rainbow-colored vests that identified them as “companions” to differentiate themselves from those who come to protest outside the center. Some have been helping out for the past couple of weeks. Judy (not her real name) started coming in February because she is “convinced of the importance of access to women’s health,” and that if she doesn’t “do something, it will soon be too late.”

Across the street, Jacob Gibson was waiting with a sign that read: “We love you and want to help you and your baby.” A “Christian in his twenties with no children,” Gibson works at a fast-food restaurant and spends his day off outside the clinic, which is a 45-minute drive from his home in Muskogee. He goes every Wednesday, rain, hail or shine. Last Wednesday it was raining buckets.

Within an hour, four cars pulled into the parking lot outside the clinic. Gibson’s followed the same process of every arrival. He threw himself on top of the cars and shouted phrases such as “I hope you love your baby as much as yourself,” “there is still hope” or “that child wants to live.” The pro-choice volunteers at the clinic approached the women and escorted them with their umbrellas, because, if not, they say, the anti-abortionists record them from the street and share the images online. As the patients left the clinic, Gibson shouted at them the address of a website that offers a treatment to undo the effects of the abortion pill.

Andrea Gallegos, the clinic’s executive administrator, explains that the protesters “can be very aggressive, not only with the patients, but also with the employees.” “They know our names. It’s pretty horrible,” she says. According to Gallegos, the anti-abortionists sometimes manage to lead potential patients to a “fake consultation” across the street that is run by an organization called GoLife. There, the co-directors of GoLife – two distrustful women in their sixties who preferred not to tell EL PAÍS their names – perform “free ultrasounds and pregnancy tests.” They also stated that they give directions on where to get “help at home, financial loans and food,” and that they offer “free baby showers.” Gallegos warns that at sites like this it is common for women to be deceived about “the week of pregnancy they are in, so that when they want to have an abortion it is too late.”

Before Governor Stitt signed the anti-abortion law, women in Oklahoma could terminate pregnancies up until about 23 weeks. The new six-week limit, which comes into effect this summer, will make it nearly impossible to obtain an abortion. “Many [women] don’t even know they’re pregnant then,” says Emily Wales, interim president and CEO of the Great Plains affiliate of Planned Parenthood, a national organization based in New York and Washington with chapters in more than 40 states. Planned Parenthood Great Plains (PPGP) also has a center in Tulsa (in total, there are five registered clinics in Oklahoma). “At the earliest, they find out after four weeks, and they don’t have time to get an appointment, because appointments are booked up one month ahead. That pushes them to Kafkaesque-like situations, where they ask for an appointment before taking a [pregnancy] test, just in case,” she adds.

These difficulties are compounded as more states introduce bans, and patients are forced to seek help elsewhere. According to estimates provided by the Center for Reproductive Rights, consultations in Oklahoma rose “2,500%” after neighboring Texas passed its law. It’s a fact that has been bandied about by Oklahoman Republicans in Washington. Senator Greg Treat called the recent spike in abortions “a state of emergency.” According to figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of abortions performed in the US fell by half between 1986 and 2019, dropping from 1.3 million to 630,000.

Tulsa Women’s Health Clinic has begun sending women to a center in Little Rock, Arkansas, a four-hour drive away, and to another in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a nine-hour drive away, where they administer abortion pills but do not perform surgical abortions. The problem is that many women cannot pay for these trips.

Nash says that some places do not allow women to have an abortion the same day they go in for a consultation. The idea behind this rule is so that women can sleep on it and reconsider their decision. “Another fallacy,” according to Nash. “At the Guttmacher Institute, we have studies that say that between 92% and 95% [of women] are convinced of what they are going to do before making an appointment.” Many women are also not granted permission to leave work to travel for an abortion, so they lose up to four days worth of pay, which must be added to the costs of the procedure itself (some large companies have announced special measures to help employees in this situation). “An abortion costs about $550, and then there is gasoline, hotels, food… having an abortion in another state can cost about $1,000. It is simply too much money for most, who will not be able to afford it. This only exacerbates inequality,” says Nash.

Wales, from Planned Parenthood, says that they decided to stop giving new appointments at their Tulsa clinic in April “until we see what happens.” PPGP’s area of operation includes Oklahoma, Arkansas, western Missouri and Kansas, the only state where they still have a little margin, although its days may be numbered: in August, Kansas plans to vote on an anti-abortion bill. “It is simply not sustainable, we cannot attend to all the patients who ask us for help,” says Wales, who explains that many of the doctors who perform abortions “do not live in the states in which they practice,” due to “the violence” they face at their workplace. Despite everything, PPGP does not plan to close its clinics, because “most” of its consultations are to provide information and reproductive assistance or procedures such as breast cancer screening tests. From now on, adds Wales, they will be taking on a new task: supporting women who have traveled interstate to get an abortion once they return.

Together with the Center for Reproductive Rights, PPGP has sued the state in the Oklahoma Supreme Court over S. B. 1503, which they say provides such limited and difficult-to-prove exceptions (other than when the life of the mother is in danger) that they are “nearly unusable.” Wales doesn’t have “much hope” for a win. “Least of all,” she says, “since they’re about to topple Roe v. Wade in Washington.”

So what will happen if the Supreme Court overturns the landmark ruling? According to Paul Collins, professor of law at the University of Massachusetts, Judge Samuel Alito seems to have written the draft opinion as if he “had the 1973 sentence in his hands.” “It’s as if he wanted to amend the Supreme Court precedent from 50 years ago,” he says. Mary Ziegler, a historian on reproductive rights, whose most recent book is titled Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present, is also concerned about what may come next on the political front. “Everything indicates that if the Republicans regain power in 2024, they will try to pass a federal law that makes abortion illegal throughout the country, without safe-haven states,” says Ziegler.

Neither of these two experts was surprised by the draft opinion. Nor were the activists who spoke to EL PAÍS. But that hasn’t stopped the news from Washington from falling like a bombshell, plunging the reproductive health rights movement into a mix of stupor, anger and despair.

A state of mind that was perfectly defined by rock legend Patti Smith at a concert on Friday in Tulsa. “Do you want us to talk about Roe vs. Wade?” she asked the crowd. “It’s terrible. And I don’t have an answer. I can only tell you what we would have done when I was young: disobey!”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.