Living to tell the tale of Covid-19

During the toughest months of the pandemic, Juan Altares suffered all the complications of what was then a completely unknown disease. This is a day-by-day account of how his family got through it

- “Quick! Quick! He’s slipping away!”

- “He can scarcely move his eyebrows!”

- “It’s alright Juan, it’s over now”

My brother Juan:

50 days in a coma from the coronavirus

Ir al contenido

My brother Juan’s last memory before entering an induced coma is of being in the emergency ward, surrounded by nervous doctors. He was asked for the contact number of a close relative, and he still had the strength and recall to give them the that of his wife Pilar. While the health workers explained that they were going to have to sedate him, he could hear voices in the background saying, “Quick! Quick! He’s slipping away!” At that moment, his heartbeat was not strong enough to keep him alive – it was beating at less than 10% of its capacity compared to the 60% to 70% of a healthy heart; the doctors did not understand what was happening. Until then, they had not seen heart failure in a Covid-19 patient. It was April 4, and Spain was at a critical point of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic and the hospitals, including the Fundación Jiménez Díaz in the Madrid district of Moncloa, were near full capacity.

Juan’s next memory is of lying in an intensive care unit (ICU) bed, with Pilar saying, “It’s alright, Juan, it’s all over now.” It seemed like the blink of an eye but, in fact, my brother had spent 50 days in a coma, during which time he suffered all the complications that coronavirus can entail – heart failure, bilateral pneumonia, secondary infections, kidney failure and paralysis of the nervous system. He narrowly escaped death three times; the last time, the doctors were close to throwing in the towel. But they did not give up. Neither did Juan.

This is the story of a critically ill patient during a pandemic that could be summarized in one word: loneliness. It is the story of Juan, asleep and isolated in an ICU cubicle. But it is also our story, the story of his relatives, each of us shut away in our homes during the spring lockdown, glued to the phone, waiting for news that could be of his death. The only time I was separated from my cellphone was in the shower and even then I had the phone playing music so that I would know if they called when the song stopped. I think my family broke the world record for how fast a phone can be answered. Outside, there was just the silence of an inhospitable, deserted Madrid, where even taking down the trash had started to seem intrepid.

Juan’s case, like that of so many others, began with a slight fever.

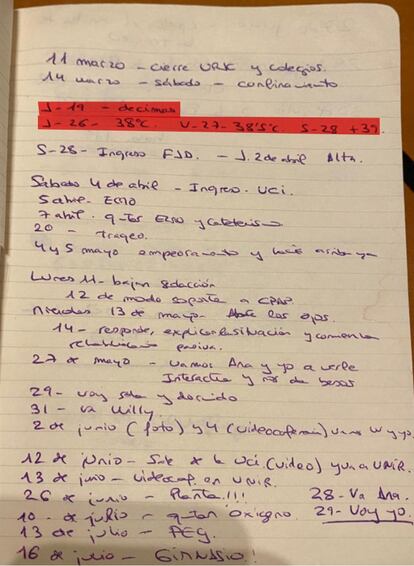

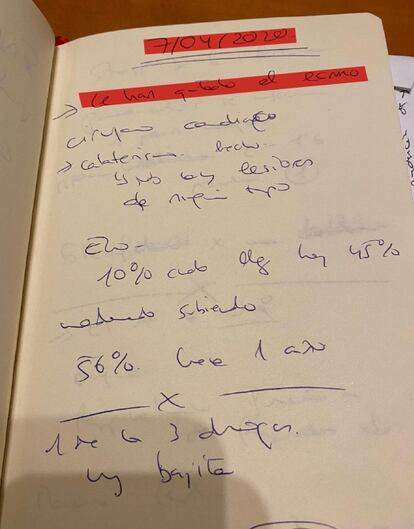

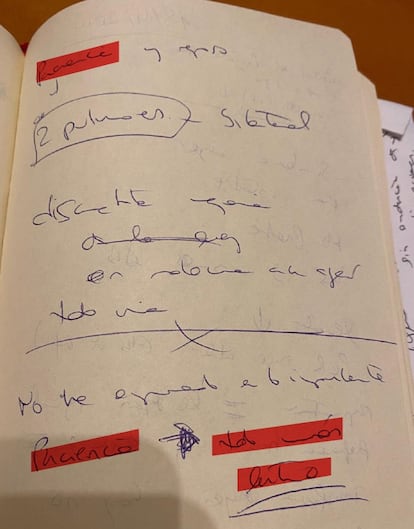

Notes written by Pilar, Juan’s wife, during the time he spent in the hospital, which appear throughout this report. In red, Pilar has written down Juan’s temperature

The first hospital admission

Married for almost 30 years, with no children, Juan, 53, is manager of the Spanish Railways Foundation’s Cultural Action and Communications department. He is a diver, traveler, handyman and yogi, a man who loves the countryside, and is known for being witty, meticulous, tidy and sociable. But his life was turned upside down when, on the Wednesday of the first week of lockdown in mid-March, the virus came knocking at his door.

Juan has never been able to confirm where he caught it, but it was possibly at a business meeting. He was scared, but he was not in a high-risk group due to his age and the fact he had no major health problems. His only health issue was diabetes, which he had under control. On Friday, March 27, his fever rose to almost 40ºC and, following the advice of his niece Ana Suero, then a resident doctor at Segovia’s General Hospital, he took himself to the Jiménez Díaz emergency room on Saturday morning. It was the first time he was admitted to this hospital and the diagnosis was pneumonia.

His fever went down and, in a few days, he was better. He showered alone, talked on the phone and watched shows on his tablet. He had had no need of oxygen and was discharged the following Thursday. Telling my friends the news on WhatsApp, I wrote a very positive message:

GUILLERMO ALTARES

The ensuing relief was combined with a profound feeling of isolation: Juan returned alone from the hospital to shut himself away. He thanked me in a message for the meatballs I had left on his doormat a couple of days before. But on Friday, April 3, he began to feel weak and on Saturday he woke up in such a state that his wife called an ambulance. The disease took hold of my family as it did society as a whole, robbing us of the life we’d lived until then.

Critical state

Juan could barely move, although he thought the sudden deterioration in his condition was due to a rise in blood sugars. He coughed spots of blood onto his handkerchief. As it was the height of the pandemic, the ambulance took forever to come. Meanwhile, Juan was slipping away. Increasingly worried, his niece told him over the phone that there was not a minute to lose. When he arrived at Jiménez Díaz hospital, his condition was critical. The messages he sent us from the emergency department were brief and gave no hint he was aware of the tsunami that was being unleashed on his body: “Checked now;” “They’re giving me more insulin;” “And something else – let’s see if it works;” “They think it’s a lung infection.” The last message was premonitory: “I’ll probably stay in the hospital.” Then silence. It was April 4. He didn’t use his cellphone again until June 17.

But it wasn’t the lungs or the blood or his sugar levels that worried the doctors. “His heart was barely beating,” explains Gonzalo Aldámiz-Echevarría, head of cardiac surgery at Jiménez Díaz hospital, who was on duty that Saturday. It was the first time the doctors at the hospital had seen SARS-Cov-2 attack the heart. In fact, some thought he was suffering from a previous, undetected heart condition. But Aldámiz-Echevarría, a diver like Juan, knew it was a sport that called for regular checkups for heart conditions.

The medical team had to resort to an ECMO*, a complicated machine that is only used in critical cases. It performs the functions of the heart and lungs and amounts to a very aggressive therapy with a survival rate of just one in three – I made the mistake of looking up the statistic online. “Juan was the first case I saw of this type of cardiac impact from SARS-Cov-2,” explains Dr Alejandro Durante, who was then on the ICU team treating my brother, and who is now in the Cardiology Acute Care Unit at the 12 de Octubre hospital in Madrid. They told us that we would have to wait a week to know if Juan was going to make it.

“ECMO” stands for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, a machine that provides cardiac and respiratory support

We had to call our mother, Pilar, or Peli, as everyone calls her. She lives alone and when she received the news she was going to feel more alone than ever. But we had to tell her what was going on, to explain via a cold and distant phone call that Juan might not be with us the next day. We did not, of course, put it in those terms but neither could we hide the seriousness of his condition. I have since forgotten the exact conversation, but not the feeling of impotence and sadness that accompanied it.

It was the middle of the spring lockdown and we could not go to the hospital to wait for news together, nor see the doctors’ faces, let alone enter the ICU, nor console each other in person. We could do nothing but wait in an empty and frightening city. What’s more, it was impossible to escape from the news about the virus, which was all over the media. It was not easy, given this panorama, to remain optimistic: it was impossible to ignore the fact that many critical patients did not make it. However, during the night they managed to stabilize Juan. Two days later, we were told that the ECMO had been removed, his heart had almost returned to normal and they were thinking of waking him up for the weekend. What we didn’t know was that this was just the start of his problems.

On the brink of death

GUILLERMO ALTARES

GUILLERMO ALTARES

GUILLERMO ALTARES

Encouraged by Juan’s progress, optimistic messages pinged from cellphone to cellphone. But the worst was yet to come. In the following weeks, Juan got a superinfection – respiratory failure caused by bilateral pneumonia, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which paralyzes the nervous system, and kidney failure, which forced the medical team to put him on a hemofilter*. There was a moment when nothing in his body worked. His organs had responded aggressively to the virus’s assault and the inflammation and pneumonia had blocked his lungs. At times, the ventilator he was using with a tracheotomy was working at full capacity and was still not enough.

*Hemofilter is a machine that does the job of the kidneys

Doctors’ calls invariably came at different times. Due to the number of critically ill patients coming in, the stress in the ICU was so bad that it was impossible to establish a set time to be in touch with families. Despite this, they called without fail for 70 days, apart from two occasions when they applied the rule of “no news is good news.” We – Pilar, Peli and I – established our own routine of talking after the nightly 8pm applause for healthcare workers. Sometimes we would talk about the news we had received that day and other times we would try to keep it lighter.

My sister-in-law decided that Ana Suero, Juan’s niece, should be the one to receive the call: she would then put it into layman’s language for us. As the alchemist Zenon from Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel, Opus Nigrum, says: “He never bathed the truth in a sauce of lies to make it more digestible.” A lot of the time, it was not easy to break the news. Pilar would write everything down in a notebook then share the news with others. The later the call, the more nervous we were, but we couldn’t talk to each other either because ... we were waiting for the hospital to call. Exacerbating the anguish caused by Juan’s situation was the impotence caused by the distance between us, and our mother’s loneliness. Later, we each sent dozens of messages to an ever-widening circle of people who, without actually knowing my brother, kept track of his progress as though they did.

GUILLERMO ALTARES

We dealt with new medical terms every day with loving and patient help from Ana and a childhood friend, Mercedes García-Gasalla, who works at the Son Espases hospital in Palma de Mallorca, and who has treated numerous Covid-19 patients. When things looked as though they couldn’t get worse, she used a phrase we would repeat to each other over and again: “Juan is young. He has a better chance of getting out than not getting out.”

However, in late April and early May, it was very difficult to hold on to any thread of hope. Lara Colino, the deputy head of the ICU at the hospital, who looked after Juan almost from the start, recalls: “There were several times when we were about to throw in the towel. It is an illness that requires a lot of patience, because there are patients who go days and sometimes weeks without progressing and with constant complications. Apart from medication that was then beginning to be used against Covid, such as corticosteroids, one of the remedies that proved to be most effective was the so-called prone position that involved turning the patient around every 12 hours.

“Patience” is one of the words that appears most frequently in Pilar’s notes

The combined efforts worked. After the peak of the crisis, there was a turning point, as though Juan’s body had been restarted. Everything changed in a matter of days. No one told us that he was out of danger, but the doctors were able to cautiously imply the news was good. “Things are going well,” they explained. Now it was time to wake Juan up. But we were not prepared for that either. More to the point, neither was Juan. After 50 days in an induced coma, when he emerged, my brother would realize he could not eat, drink, speak, breathe, urinate or move. We were certain that he had survived. But we still did not know if he would regain consciousness and be himself again.

A long awakening

The long process of waking up began in mid-May. Doctors began to take him off the respirator for a few hours at a time (a process they call “weaning”), to suppress his hemofilter for short periods and lower his medication to bring him out of the induced coma. We anxiously waited for updates: for how long had he been taken off the respirator, how many liters had he been able to urinate, how was his pneumonia improving, whether he had opened his eyes and whether he was able to look at the care workers when they said his name. “He could barely move his eyebrows when he woke up,” recalls Sarah Heili, associate head of the pulmonology service and head of the Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit (IRCU).

On Wednesday, May 27, Pilar finally received news that she could visit him. Full of wires and surrounded by machines, Juan got nervous when he recognized her – one of the sensors started beeping insistently. She told him about all of us, especially about Peli, our mother. It was one of the most emotional moments of all those terrible weeks. We were allowed to go and see him briefly every two or three days: the doctors considered it very important that he recognize people close to him. His level of awareness increased greatly when my sister-in-law flagged up a crucial detail: without his glasses, all Juan could see were formless shapes. After putting them on, he was much more alert and less confused.

It was something as simple as this that speeded up the process of awakening, even though there were setbacks. The first time I went to see him in the ICU, he was barely able to open his eyes. As one nurse told me graphically: “With all the drugs we’ve put in him to keep him asleep, no wonder he’s taking so long to wake up.” Until his tracheotomy was closed on June 10, he was unable to speak. His first word was not exactly epic: the nurse said, “Juan say something,” and Juan replied, “Something.” There was no Goodbye Lenin moment when Juan became suddenly aware of everything: the process was gradual, exasperatingly slow. We were all afraid that he would remain in that limbo forever. He remembers nothing or very little of that period: he doesn’t remember seeing our mother on a tablet, or my visits, or even when I spoke to him about Zucchero, his favorite musician. Nor does he remember the moment when he left the ICU on a stretcher, amidst applause from the medical staff, which Pilar recorded on video. It is a recording that the family cannot yet watch without being moved and that my mother and I watched on loop through our tears at an outdoor café by the Manzanares River where we had arranged to have lunch.

By that stage, the time slots for outdoor activity were over, meaning we didn’t have to bend the rules to see one another. When those rules were in place, I would ride my bike to my mother’s house, as you could ignore the one-kilometer-from-your-home limit if practicing sport, and we would chat, me on the street and her on her second-floor balcony. Curiously, communicating virtually was almost more personal as the whole neighborhood was privy to our conversation.

All’s well

Whatever could go well, went well. As the days passed, Juan became aware of his whereabouts, that he had spent a lot of time in the ICU and that he had a long way to go still as a hospital patient. From the ICU, he went to the respiratory unit, and from there to the ward, but he was still far from being independent. He didn’t even have the strength to handle a cellphone, so getting up and walking was an unthinkable challenge, and he was fully aware of that. It was great that he was so lucid because it showed that he was back, but at the same time, it relentlessly exposed him to the limitations of his own body.

One July afternoon, they took him off the oxygen. It was a huge step that happened with surprising normality. But he still could not swallow; he was fed through a tube and hydrated through a tube that also pumped him full of medicines, and he urinated with the help of another tube. We wanted to think that this was a transitory process and that he would recover. The doctors were almost certain, but the possibility that something could go wrong was always hanging over us. And then, one morning in late July, we were told that he was being discharged – but he couldn’t go home yet.

GUILLERMO ALTARES

The magic mountain

After 118 days, Juan left the Fundación Jiménez Díaz hospital on July 30. His destination was the Fuenfría hospital, a center formerly for those suffering tuberculosis in Cercedilla, 50-odd kilometers from Madrid. It is in the heart of the mountains, with plenty of fresh air that smells of rockroses in summer. The building itself was designed by Antonio Palacios, one of the most important architects in the history of Madrid, who also designed the emblematic Círculo de Bellas Artes building and Cibeles Palace. It was inevitable that The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann would come to mind – Mann wrote the novel when his wife was being treated for a lung condition in Davos, Switzerland. The aim of bringing Juan here was to enable him to stand on his own two feet when he returned home.

There, in the heart of the mountains, Juan spent most of the day alone in his room after doing exercises in the gym, occupational therapy and speech therapy sessions. He was isolated as he still carried an ICU bacteria. During those long summer hours, he read, watched television, communicated with the world through technology and dreamed of being able to eat. But he also feared that he would not have a total recovery. At this point, his health problems had less to do with Covid-19 than with his extended stay in the ICU.

The visits were organized in a trickle, but for the first time, he was able to see a few friends and family – once a week for an hour. Until then, he had only seen Pilar and me. He confessed that the isolation was taking its toll. It was months before he would be reunited with our mother. But, unlike the most difficult moments of his illness, the rest of us were no longer separated. In fact, we had moved to the family home in Segovia. What should have been normal – being together when misfortune strikes – had become extraordinary. The summer was a constant emotional rollercoaster. My brother made a little bit of progress each day. He started to walk around the room, was able to move his left hand better – his right hand was still almost paralyzed. But the slowness of the improvements, and the fear of what he might be left with, hovered like a cloud over his mood. A coronavirus outbreak in the hospital forced him to be isolated again and, in the end, precipitated his discharge – his return home.

The return home

On Monday, September 28, after a whole morning of waiting and paperwork, Juan left Fuenfría in the early afternoon. He had spent two days short of six months in hospital. Two seasons had passed and a third was underway – spring, summer and autumn. He walked into his home to gaze at the horizon once again from his balcony. That Monday, our mother was able to see him for the first time. Like when he was taken off oxygen, the reunion that had been longed for also unfolded surprisingly naturally. When our mother arrived and the son she had been on the verge of losing so many times during so few weeks surprised her by unexpectedly opening the door, there was more laughter than tears. The separation had not turned out to be so drastic after all: the screen had kept us closer than we thought.

Juan still has appointments with different doctors several times a week; he has an intense rehabilitation schedule ahead and has put on as much weight as he can. He walks without any problems, although he gets tired. His right hand is getting better – he thought, when he left the hospital, that he would never get the use of it back – and he gives himself all the culinary treats he can, including a weekly cocido, the chickpea-based stew Madrid is famous for, although he still hasn’t dared to eat steak, which he has been dreaming of doing since his time in Fuenfría. He is well, in good spirits, cries easily and is keen to get going with the rehabilitation.

No doctor has been able to say why SARS-Cov-2 attacked Juan so brutally. John Hersey, author of Hiroshima – one of the most beautiful books on human resilience – sums up his and, to some extent, our long journey: “The great themes are love and death. Their synthesis is the will to live. I believe that humanity has demonstrated that it has extraordinary resources to try to stay alive, no matter how bad things get.” Juan has been through a lot, but he is alive.

- Credits

- Coordination and format: Guiomar del Ser and Brenda Valverde

- Art direction: Fernando Hernández

- Design: Fernando Hernández and Ana Fernández

- Layout: Nelly Natalí

- English version: Heather Galloway

- Image of Juan Altares: Uly Martín