The incredible story of ‘Megalosaurus’

The discovery of the first dinosaur fossil described by science 200 years ago brought with it legends, zoophagy and the first major scientific marketing campaign

In 1824, Megalosaurus Bucklandii was the first dinosaur to be described by science. It was then revealed that the Megalosaurus Bucklandii was a bipedal carnivore that weighed a ton, measured between six and nine meters long and lived more than 160 million years ago, though the fossil had previously been thought to be the scrotum of a giant human.

The scrotum theory was pedaled by British naturalist Richard Brookes who, in 1763, on an impulse of creative audacity, gave a new twist to the interpretation of the fossil that had already been published and illustrated 86 years earlier by Oxford’s first Chemistry professor, Robert Plot in the book A Natural History of Oxford-shire. Although Plot admitted the possibility that the fossil was the remains of a giant human, he also considered it could belong to an unknown animal. The lack of certainty was due to chapter six of Genesis which speaks of a type of colossal and violent demigod that would have been swept away in the great flood. Since any explanation beyond the purely biblical was impossible to imagine in that era, findings and hypothesis had to coincide with the theological worldview.

Paleontology student, author of Women of the Stones and skillful disseminator, Fernanda Castaño uses her blog to compile odd paleontology stories, complete with documentation. And she could find no justification for such a bizarre theory. “Richard Brookes inexplicably catalogs it [the fossil] as Scrotum Humanum and describes it as something that could have been the limb of a giant, but there is no explanation as to why he names it that way,” she says. The label did not fit Linnaeus’ binomial nomenclature for classifying animals and plants, so it was renamed.

More than just a funny anecdote, this strange, if brief, failure to correctly identify the fossil reflects the evolution of science. “Throughout history, bones were ascribed to giants, and there was no need to look for evidence because if the Bible said so, then it was so,” explains Castaño, who is also an epistemology enthusiast. “They didn’t have any doubts. That’s why the Industrial Revolution — the context in which this finding takes place — is so important. Because what happens is a break with that paradigm. It gradually begins to reveal that there is a history that is much, much older. When they begin to excavate to build roads, to obtain minerals, they reveal strata with increasingly longer timelines and a history that is much more remote than what the scriptures suggest.”

According to Castaño, for historians such as William John Thomas Mitchell, “dinosaurs are the first modern animals because they are the ones that allow us to break with the paradigm of God the creator.” And Megalosaurus did so in a particular fashion. As well as being a naturalist, geologist and paleontologist, William Buckland, the author of its scientific description in 1824, was a clergyman, so he had to find a way around the contradictions the scientific evidence presented him with.

A researcher at the Complutense University of Madrid, Angelica Torices Hernández, explains that “when Buckland realized that Megalosaurus was carnivorous, he found himself in trouble” because according to the Christian faith that “was associated with violence, and evil had only begun on Earth with human decadence — with original sin. In the Garden of Eden, everything was peaceful and beautiful, and this carnivorous beast did not fit, it could not have been created by God. So, Buckland justifies it by saying that it is a perfect killing machine, capable of causing death without pain, so God created it to eliminate suffering in an effective way.”

Unique jaw

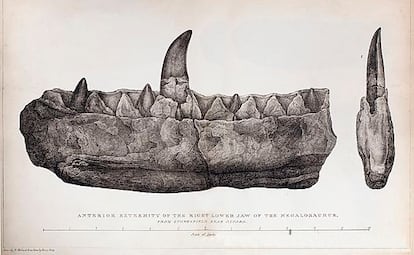

More than a century had to pass before the confusion between giant humans and colossal reptiles could begin to be clarified. The fossilized femur studied by Plot in 1677 regained unexpected relevance when another key piece of what would become the most important puzzle in the history of dinosaurs turned up. In 1805, a professor of anatomy brought Buckland a unique jawbone that he had bought in one of the many geological markets popular in England frequented by wealthy collectors.

In that fragment “there were very particular characteristics, which had to do with the fact that it was not from a large mammal or any other animal known at the time,” says Castaño. “Inside the jaw, there were some alveolites, where the teeth are inserted, and there were also fragments of teeth that would be replacement teeth, a characteristic that not many animals present.” Both this fossil and the femur came from Stonesfield; later a hip, vertebrae and sacrum of the same origin would be added. Like Frankenstein’s monster, using fragments of the same species but from different individual animals, Buckland was able to recreate the anatomy of the great lizard.

“Crucial to dispensing with the idea that it was a fossil of a giant human were the letters between Mary Morland, a professional paleo-illustrator and Buckland’s wife, and Frenchman Georges Cuvier, who was the great anatomist of that period,” Castaño explains. “He is the one who tells Buckland that he is right; that this was a large animal and that it was probably a saurian, a lizard. Armed with this data, when Cuvier travels to England in 1818, he meets Morland, observes a live lizard and confirms this conclusion.” Buckland presented his study six years later when he formally became president of the Geological Society of London.

Dynomania

However, as Buckland expounded upon his theory, another beast stole the audience’s attention. A nearly complete skeleton, more than five meters long, with fins and a long neck, dominated the room. Found and reconstructed by Mary Anning, the most prolific unrecognized paleontologist of her time, the Plesiosaurus was the largest aquatic creature of its era. “It was a huge critter, with all the little bones displayed, living in the deep,” says Castaño. “In contrast, Megalosaurus had some bones, a hip, a femur, some vertebrae, and a jaw worthy of attention, but it was not so remarkable.”

To bolster its significance, the Buckland fossil needed the subsequent support of two colleagues, paleontologist Mary Anne Woodhouse and her husband Gideon Mantell, a renowned naturalist and surgeon. “When Richard Owen, a British paleontologist and anatomist, describes dinosaurs for the first time, he uses characteristics, such as the fused vertebrae of the sacrum which is what you can see in one of the fragments that Buckland describes, and also in the remains of the Iguanodon discovered by Mantell,” says Castaño. “Later, with the Hylaeosaurus, the second dinosaur to be found by Owen and the third in general, the group is defined. These three genera had the characteristics that define dinosaurs and allowed Owen to differentiate them from other animals that had been found, establishing the dinosaur genus in 1842.”

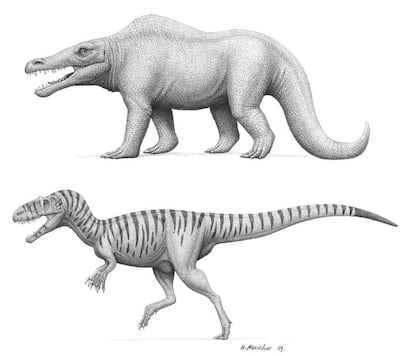

The anatomist went on to explain that Megalosaurus was a theropod capable of standing on two legs. “Initially, they were reconstructed as lizards about four to six meters long, stocky, large, quadrupedal,” says Fernando Novas, a researcher at Argentina’s National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET). “Then it was discovered that they were not, and that was what Owen introduced. He realized that these were animals that had columnar legs that were not shaped like those of a lizard or a crocodile. There is already a difference in the way in which the image of a dinosaur in general and of Megalosaurus in particular evolved.”

While Owen’s Iguanodon was the first to prompt scientific study, Buckland was quicker. Once he gathered and reviewed all the Megalosaurus findings, he rushed to become the first to publish his description on February 20, 1824. The fascination with dinosaurs was kindled. Dr. Torices Hernandez says that “Richard Owen was a great popularizer, with marketing skills, and he created the first dinomania” by recreating all the dinosaurs known so far in the Crystal Palace Park, in London, with the aim of reflecting the scientific and technical advances of the British Empire. “It aimed to show an antediluvian garden and was highly publicized. Scaled down models were even made of these animals — dolls for educational purposes that he sold for £30 [$38]. There was merchandising: comic books, comic postcards, chocolates with stickers,” says Torices Hernández. Megalosaurus also had its exclusive moment of fame in the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’ novel, Bleak House, marking the first instance a dinosaur appears in fiction.

The charismatic zoophage

William Buckland would have eaten his own dinosaurs if he could. As well as being a theologian and paleontology pioneer, he was, according to Castaño and the Geological Society of London’s blog, an eccentric zoophage. He belonged to a club of carnivores who liked to get together to try all kinds of meat: moles, bluebottles, capybaras, crocodiles, panthers, elephant trunk, rhinoceros, kangaroos and even the heart of a king, according to one story. “In the 19th century, he belonged to a zoophagy club where they tasted every kind of meat in existence,” Castaño says. “Exotic animals; you name it, they tasted it. And he had the habit of saying that he had tasted all known animals except humans.” The geologist shared this peculiar hobby with his family. His son Frank founded the Acclimatization Society, joined by Richard Owen, whose ultimate goal was to devour the entire animal kingdom.

In 13th century France, the heart and other internal organs of the body of a dead king or queen were given special treatment. According to a blogger who calls himself simply Paul and specializes in curious tales related to geology and paleontology, the heart was embalmed and placed in an ornate reliquary, which in turn was placed on black taffeta-covered cushions placed on the lap of the king’s confessor.

Under cover of darkness, a funeral procession carried the royal heart to its final resting place, often at a different location from the body, usually specified by the monarch before death. During the French Revolution, as well as beheading royals, the revolutionaries sold their mummified hearts. Legend has it that a painter interested in the exclusive brown pigment used for mummies, acquired the organ and used it for his paintings. What happened to the rest of the heart, Paul says, is a matter of conjecture, as there are conflicting claims.

According to one version of the tale, the artist returned the remains of the heart to the royal court after the Second Bourbon Restoration put Louis XVII on the throne. An alternative version exists in the Val de Grâce church in Paris. The latter has it that at a dinner party attended by Buckland, the shrunken remains of the heart were passed around the table for the guests to inspect. When it reached Buckland, he declared, “I have eaten many strange things, but I have never eaten the heart of a king before,” and proceeded to wolf it down.

Buckland’s eccentricity gave him a platform on which to present his research in a theatrical fashion not unlike today’s scientific stand-ups. Much of that style and his work is still influential 200 years after he published the first scientific description of a dinosaur.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.