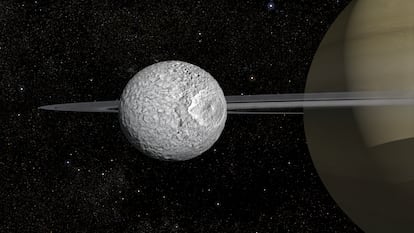

Underground ocean found on Saturn’s moon Mimas

The discovery on the satellite shows that these types of seas that could harbor life are abundant in the Solar System

When most people think of where extraterrestrial life could exist, they think of Mars. But there are other worlds within our Solar System where life is also possible. Covered by tens or hundreds of kilometers of rock and ice, the underground oceans of some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn remain warm enough to have liquid water and have chemical conditions where terrestrial microorganisms could survive.

When the Voyager 2 probe passed by Jupiter’s moon Europa in 1979, it observed grooves and fractures in the frozen surface that raised suspicions about what was hidden inside. After decades of observation it is believed that, in addition to Europa, there are vast bodies of water inside Ganymede, the largest moon in the Solar System; on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which shoots plumes of water vapor and other chemicals into space; or on Titan, whose surface is covered with lakes of methane. Now, an article published in Nature suggests that there is also an underground sea on Mimas, another of Saturn’s moons.

The existence of an underground sea can usually be discerned by changes in the moon’s surface, such as the faults on Europa, which are caused by changes in the volume of water when it freezes or melts. But Mimas, a world that seemed geologically dead for a long time, does not have faults

However, the authors of the study published in Nature, led by Valery Lainey, from the Paris Observatory (France), found the presence of water thanks to a detailed analysis of Mimas’ movements around Saturn. This small moon, which is only 400 kilometers in diameter, would have its liquid ocean under a layer of ice 20 or 30 kilometers thick. Simulations suggest that the sea appeared recently, between 25 and two million years ago, which is insufficient time to cause visible effects on the moon’s surface.

Olga Prieto, head of the Planetology and Habitability Department at the Astrobiology Center in Madrid, considers that the most interesting thing about this work “is that it shows that in worlds where there is no external sign that they exist, there may also be oceans.” This makes it possible that underground seas in our Solar System are more the norm than the exception. In addition to the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, other bodies such as Vesta, in the asteroid belt, several satellites of Uranus, and even the dwarf planet Pluto, could have large amounts of water under their surface.

The decay of radioactive elements in some celestial bodies could explain the heat source necessary for water to be a liquid so far from the Sun. In others, such as Mimas, the gravitational effects of Saturn and other moons can shake the satellite’s core with the same, but much more intense, mechanism that produces tides on Earth, causing the temperature inside to rise. This phenomenon raises the possibility that crossing the orbits of other objects could create the conditions for the ice to melt, and it raises questions about the stability of the habitats that would make life on these worlds possible.

Astrobiologist Alfonso Dávila, from NASA’s Ames Research Center, explains that although the conditions for life may now exist on some of these moons, it is not clear that life could have emerged in these environments as it did on Earth. “We don’t know the conditions under which life originated here. There are models that place this origin on the surface, with light and ultraviolet radiation playing important roles, with episodes of flooding and drying that are important for organic chemistry and geochemical evolution, and there are oceanic models, in which scientists talk of hydrothermal chimneys where the conditions for life were created. Furthermore, some of the oldest organisms are thermophiles, they like high temperatures,” Dávila explains.

However, if life could not have originated in the ocean, moons like Europa or Enceladus would be habitable, but sterile. “On Earth we don’t have those types of environments, because life colonizes all habitable places, so it would also be something interesting to study,” he says.

Despite the proximity of these aquatic worlds and the abundance suggested by the article published in Nature today, many of them are as inaccessible as the planets that orbit stars light years away. With current technology, it seems like science fiction to drill through tens of kilometers of ice, but according to Prieto, there are already crazy ideas that space agencies are listening to as possible long-term plans. The Exobiology Extant Life Surveyor is a robotic worm that could crawl through the cracks that Enceladus’ plumes emerge from and reach its ocean, dozens of kilometers below the surface.

It seems even more difficult to reach the newly discovered sea on Mimas, which is hidden by a surface that gives the impression of an inert world. If it were possible to reach its interior one day, Dávila believes that we would not to find life there. “The models tell us that life on Earth appeared relatively quickly in geological terms, but perhaps it took 200 or 300 million years,” he says. On Mimas, where the ocean is only 25 million years old, there would not have been time for life to develop yet, but an environment could be found in which simple molecules begin to combine to form more complex molecules such as DNA, which later made life possible. “On Mimas, we could study that very interesting time in the phases prior to the origin of life that we do not have on Earth, because the geological record has been destroyed,” says Dávila. For now, the Mimas ocean is a new surprise that changes expectations about our cosmic neighborhood.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.