A library of human defenses

Sick of genomes, proteomes and microbiomes? Get ready: the Human Immunome Project is coming

There is a dominant trend in biology for the elaboration of catalogs: genome, proteome, exome, metabolome, microbiome. The suffix ome denotes that you settle for the whole, all the genes, all the proteins and whatever else it takes. Perhaps the philosophical epitome was reached in the first decade of this century with project behaviorome, which sought to compile a census of possible human behaviors. As far as I know, it never got off the ground. The blame for this librarian zeal surely lies with Charles Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish naturalist who devoted his life to making an inventory of all known living things in his time. But today, we know that biological catalogs are extremely useful in a science dominated by the exuberant complexity of the living world, and the most current such initiative will focus on our defenses.

The Human Immunome Project (HIP) was founded at a scientific congress in La Jolla, California, and its creators include some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, biotech firms, universities and government agencies, including the J. Craig Venter Institute and Spanish foundations such as ISGlobal and La Caixa. This year, they will begin collecting immunological data from hundreds of thousands of volunteers around the world, by looking at thousands of variables in their blood and tissue samples. Maybe from your blood and tissues, distant reader.

The resulting database will be available to all researchers, and will hopefully clarify which immunological peculiarities explain our health or lack thereof. It will be valuable data for the medicine of the immediate future, and even for the vaccines and drugs of the present. At the moment, it has a meager funding of $5 million a year, but aims to add two or three zeros to that figure when its results start to shine. Pfizer and Moderna, the two corporate stars of anti-Covid vaccines, are in the consortium, along with AstraZeneca, GSK, Janssen and Novavax. That’s pretty much the who’s-who of Big Pharma, folks.

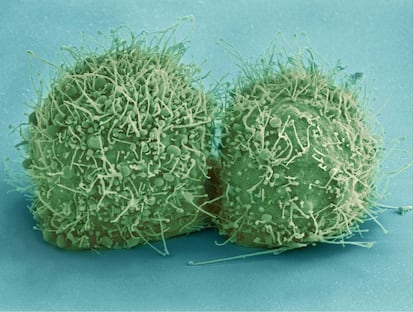

In fact, the immune system is essential to a thousand factors that determine our life and death: the diseases we contract, the way we age, how many years we live. No one has ever doubted the need to investigate it in depth, but its gigantic complexity has only allowed us to access the general principles of its functioning. The main one is its generative character, that is, its capacity to respond to environmental situations it has never faced before. It is a true prodigy of biological evolution — the Messi of genetics.

Precisely due to their generative nature, however, it is virtually impossible to catalog molecular creations. We know how this fractal and inexhaustible range of antibodies is generated, yes, but, in matters of health and human biology, the devil is in the details. Why do 10% of people fail to respond to the hepatitis B vaccine? And why does it work so well in the remaining 90%? Here it is not enough to look at one gene or a couple of proteins. You have to look at all of them and enlist artificial intelligence to lend a hand.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.