DNA from enslaved iron-forge workers linked to 42,000 living descendants in the US

An unprecedented study traces the genetic lineage of 19th century slaves buried in unmarked graves in Maryland, opening a new path for African Americans to identify their family origins

In 1977, workers building a highway in Maryland stumbled across an abandoned cemetery in the middle of a forest. The unmarked graves, it would later be determined, contained the remains of mostly women and children. The oldest dated back to the 18th century. The people buried there were Black workers enslaved at the Catoctin Furnace, an iron forge that once operated nearby. Now, in an unprecedented genealogical study, researchers have extracted the DNA from 27 of the cemetery’s corpses, shedding new light on their histories, tracing their origins back to Africa, and identifying tens of thousands of present-day relatives, including nearly 3,000 direct descendants. The project is a major and unprecedented achievement in a country where Black people were not included in the national census until 1870, and rarely have any records of their ancestry.

The vast majority of the 45 million Black Americans living in the United States are descended from the roughly half a million people who were taken from Africa and enslaved between the 16th and 19th centuries. The lack of ancestral records means that most African Americans do not know their specific family origins before the last third of the 19th century. Frederick Douglass, a Maryland slave who managed to escape, reunite with his wife, and devote the remainder of his free life to the cause of abolition, described the situation in 1855 in his memoirs. Slaves, he said, know as little about their age and origins as horses, and their masters took great care to keep it that way. “Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves,” he wrote.

The new study was made possible thanks to the support and involvement of various nonprofit associations, family members, experts in ancient DNA, and a massive gene database operated by the biotech company 23andMe, a veritable Google of genetics, with over 14 million users worldwide. A few years ago, the organizations that excavated the old cemetery near the Catoctin Furnace requested that the company search for people with genetic sequences that matched those of the 27 sets of human remains buried there between 1774 and 1850. The more DNA fragments that matched, the closer the descendants would be related. The results, published on Friday in the journal Science, tell a story that spans three centuries and three continents. Researchers analyzed the genomes of 9.2 million 23andMe customers in the US who had given permission for their results to be anonymized and used for research purposes. In the end, 41,779 descendants of the enslaved iron forge workers were identified. Among these, 2,975 had retained 0.4% of their ancestors’ DNA, meaning they are most likely direct descendants.

The great-great-great-grandchildren of the enslaved

Iñigo Olalde, a geneticist at the University of the Basque Country and a co-author of the study, explains how, for many of the individuals identified, the level of genetic kinship “is equivalent to one of the slaves being the father or mother of their great-great-grandfather or great-great-grandmother.” In other cases, he says, “the relationship is less direct, and they may have only shared a common ancestor, like a cousin.” Olalde explains: “Until now these kinds of studies were limited to DNA from living people and used only small databases; now, we have millions of people, which has allowed us to shed new light on the family history of modern-day African Americans. Unlike written records, DNA cannot be erased.”

At least five different families were buried in the cemetery near Catoctin Furnace. Most were women and children, including a mother in her thirties whose young son was buried on top of her shortly after her death. It is not known why so few men were buried there. Perhaps they were sold to other salve-owners, or were buried elsewhere. The skeletal remains unearthed from the cemetery retain the marks of a violent and abusive existence: back injuries from carrying heavy loads, dental issues, and extremely high levels of zinc from breathing smelting fumes. Genetic analysis shows that most of the enslaved people had descended through their paternal line, from men with English and Irish blood. This further corroborates historical claims that white masters raped or sexually subjugated enslaved women to produce offspring, according to the study.

The DNA reveals that the people enslaved at the iron forge had originated from the Wolof and Mandinka peoples of modern-day Senegal and The Gambia, and Central Africa’s Kongo people. “This is a level of precision that has not been achieved before,” says Cristian Capelli, a professor of human evolution at the University of Oxford and the author of one of the most comprehensive studies on the genetic origins of enslaved people in the Americas. In his earlier studies, the lineage was more mixed, and corresponded mainly to the national origins and countries of operation of slave ships. “In the case of Catoctin, we are probably dealing with a very compact group that had just arrived from Africa,” he says. “Judging by the places of origin, they most likely arrived aboard British slave ships.”

The Catoctin Furnace was fully operational as early as 1776. It employed some 270 enslaved workers who manufactured, among other things, some of the bombs used during America’s War of Independence against England. England had promised the slaves their freedom if it won the war, so after the fighting was over, the workers remained the property of their owners, who included George Washington, the first president of the United States. “If the British had won the war and kept their word, African-American slaves could have been free 100 years earlier, or roughly five

generations,” geneticist Fatimah L. C. Jackson writes in a companion article to the study. It is “disappointing,” Jackson adds, that genetics related to chronic diseases in African Americans has yet to be analyzed, given that the demographic has higher rates of cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes than other groups of European descent in the US.

In the mid-19th century, the workers enslaved at the Catoctin Furnace were replaced by wage laborers of European descent. We do not know what happened to these workers after the transition, but the study reports that most of their modern-day descendants still live in the state of Maryland. Others joined a large migratory movement out of the state, and their direct relatives now live thousands of miles away, in southern California.

Treated like animals

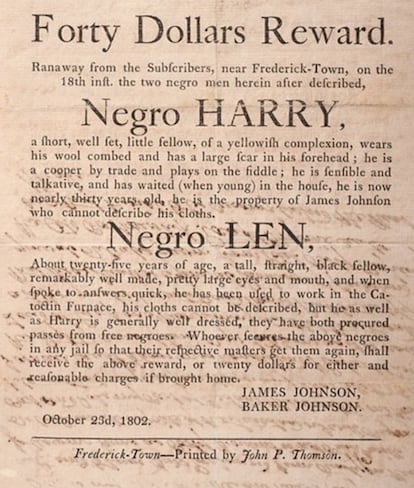

Historian Elizabeth Comer is president of the Catoctin Historical Society and her mother, also a historian, was involved in cemetery excavations in the late 1970s. Comer has spent nearly 10 years compiling official, church and personal records in an attempt to identify descendants of people enslaved in Catoctin. So far, she has been able to connect two sets of descendants with names and surnames. The first are Crystal Emory and Steve Pilgrim, the white descendants of Robert Patterson, an African American who worked at the iron forge. On the other side are the Winston sisters and their mother, the direct, African-American descendants of Henson Summers, who began his life as a slave and ended it as a free man. “My dream is to reconnect all of Catoctin’s descendants with their past,” Comer explained in a telephone interview. Among the documents she recovered are 16 newspaper advertisements offering rewards for escaped Catoctin slaves. The men are simply identified as “Negro Harry, Negro Len...” and the advertisement describes them as if they were animals, referring to their hair, for example, as “wool.

The study is so unprecedented that the repercussions of its findings remain unknown. The company 23andMe is currently considering if and how to inform its customers of their kinship with the ancestors buried in the Catoctin cemetery — they may not want to know – and is determining how to proceed in a manner consistent with privacy agreements and regulations.

At the same time, the biotech company is also in the process of analyzing the genomes of already identified offspring, in order to provide them with the results. Éadaoin Harney, a geneticist at 23andMe, explains: “Around 80% of our customers agree to have their genome used for research. That makes us the largest database of its kind in the world — much larger than any public repository. In the future, we want to figure out how to connect more people to their origins.”

“I am often asked,” Frederick Douglas once wrote, “how I felt when I first found myself in the free land... Few things in my experience have been able to give a more satisfying answer. A new world opened up to me. If life is more than breath and ‘quick circulation of blood,’ then I have lived a day longer than a year in slavery.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.