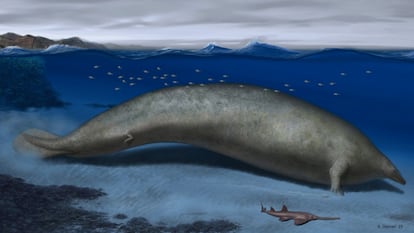

A whale from 40 million years ago is the heaviest animal that has inhabited the Earth

Found in a Peruvian desert, just the skeleton of the ‘Perucetus colossus’ weighed more than seven tons, triple that of the blue whale

The Ica Valley, in southeastern Peru, is a sandy desert, but 39 million years ago it was all sea. And in that sea lived the heaviest animal on the planet. Only a few vertebrae, ribs and part of the pelvic bone have been found, but the first weigh more than 220 pounds each, and the second measure 4.6 feet. Those responsible for the finding, published in the scientific journal Nature, estimate that the complete skeleton of this whale should weigh up to three times more than that of the blue whale, the largest animal known to date. Based on the ratio between bone mass and total mass of other whale species, they calculate that this cetacean could have weighed up to 340 tons; blue whales rarely exceed 150 tons. They have named the newfound creature Perucetus colossus, from Peru and cetus (Latin for whale) — and colossus, which needs no translation.

The first discovery, a fossilized vertebra, took place on a hill a few miles from the Samaca oasis and nine miles from the current coastline. It was found by Mario Urbina from the Natural History Museum of Lima at the National University of San Marcos. Urbina had been searching for the remains of large marine vertebrates in the scorching desert for years. The first one, which was difficult to dig out, was followed by 12 more vertebrae — all from what would have been the lower back and the lumbar region of the animal —, four ribs and the right coxal bone, which would join the pelvis with a lower extremity that, as a marine animal, it did not have. Due to its position in the stratum, paleontologists estimate that this specimen of P. colossus lived and died between 39.8 and 37.8 million years ago. It would belong to the basilosauridae family, the first exclusively marine cetaceans, that is, mammals that moved from the land to the sea approximately 50 million years ago.

Giovanni Bianucci, from the University of Pisa (Italy) and one of the authors of the article published in Nature, points out that the P. colossus is not the largest animal discovered so far. “The largest are the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) among marine vertebrates, and some extreme sauropods (such as the Argentinosaurus) among terrestrial vertebrates,” he explains. However, it had to be the most massive. Based on the size and weight of the bones found, scientists estimate that the complete skeleton would weigh between 5.3 and 7.6 tons. With this range, and knowing the skeletal mass of other cetaceans, which is between 2.2% and 5% of their total mass, they estimate that this colossus would have weighed a minimum of 80 tons and a maximum of 340 tons. The average value obtained in all the comparisons shows an average weight of 170 tons, thus surpassing the blue whale, which very rarely exceeds 150.

The key to all these calculations is in the bones. It is not just that they can be used to estimate the weight, shape and volume of the animal; it is that with only those few vertebrae and ribs it is possible to find out some key details of the life of this enormous whale. The central point, Bianucci says, is that they are not regular bones: “No cetacean, alive or extinct, has such heavy, bulky bones.” All existing cetaceans, including the largest whales, share one characteristic: their apophyses — those pieces of bone that protrude from the vertebrae — are relatively thin. But the vertebral apophyses of the P. colossus are comparatively huge and very thick. In medicine, this is called pachyostosis, although it is not a disease; in this case, it is part of the evolutionary design of the animal.

Inside, the bones of this whale are also very different. Hans Thewissen, of the Northeast Ohio Medical University, is an expert on whale morphology. Unassociated with the new discovery, he wrote an article in Nature analyzing the finding, where he helps to understand the relevance of the skeleton of this colossus. In it, he compares the cross-section of a mammalian bone to a baguette, with its hard, solid crust (compact bone) around a spongy interior (trabecular bone). Here, the aforementioned pachyostosis means that the compact part grew at the expense of the trabecular part, with the resulting densification of the bone. In addition, the vertebrae and ribs of the P. colossus have another peculiarity that in other animals (and humans) is a problem: osteosclerosis, where the increase in bone density occurs at the expense of the marrow that they have in the center.

The result of this particular bone development is a very heavy skeleton. On land that would be a problem; only animals with aquatic habits, such as the hippopotamus, have it. In the sea, only a few species of mammals have such large, heavy bones. They are the sirenians, which are distantly related to the elephants. Only four species remain alive, three manatees and the dugong. Their habitat and way of swimming would be, according to the authors of the study, very similar to that of these animals, commonly known as sea cows.

“The skeleton of the P. colossus shows a typical adaptation of diving animals of shallow coastal waters, which is an increased bone mass,” says Eli Amson, a researcher at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History (Germany) and senior author of the study. “This means that the skeleton is heavier in this animal compared to its close relatives. We have a combination of an increase in compactness (all the internal cavities of the bones are filled with more bone tissue) and each bone also thickens, due to the additional layers of bone tissue deposited on the external surface of the bones. This gives the fossils an incredibly bloated appearance.” Thus, unlike today’s large whales living in the open sea, “the extra bone weight must have affected the animal’s buoyancy (like a divers’ lead belt), giving it the proper overall density to stay in shallow waters,” concludes Amson.

The discovery of this whale in the Peruvian desert also opens another avenue of investigation. Although from their beginnings in the sea there were large cetaceans, especially elongated ones, the gigantism of animals like the sperm whale or the blue whale is relatively recent (about five million years ago). The new colossus, with its 65 feet and its potential 340 tons, entails setting back the appearance of gigantism in the sea by almost 35 million years. As for its diet, having not yet found its head, it is still a mystery. The authors suggest that it could have been a scavenger, catching whatever sunk to the bottom. Asked by email, Thewissen concurs: “As it must have spent a lot of time at the bottom of the ocean, its food was probably there. Maybe buried animals, shrimp and fish. Gray whales dig into the ocean floor in search of food.”

The Peruvian paleontologists started a funding campaign so that Mario Urbina, who found the first vertebra of the P. colossus, can finish searching the desert for the remaining parts of this and other whales.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.